What is Information Architecture?

Information architecture (IA) is the practice of organizing, structuring, and labeling information to make it easier to find and understand.

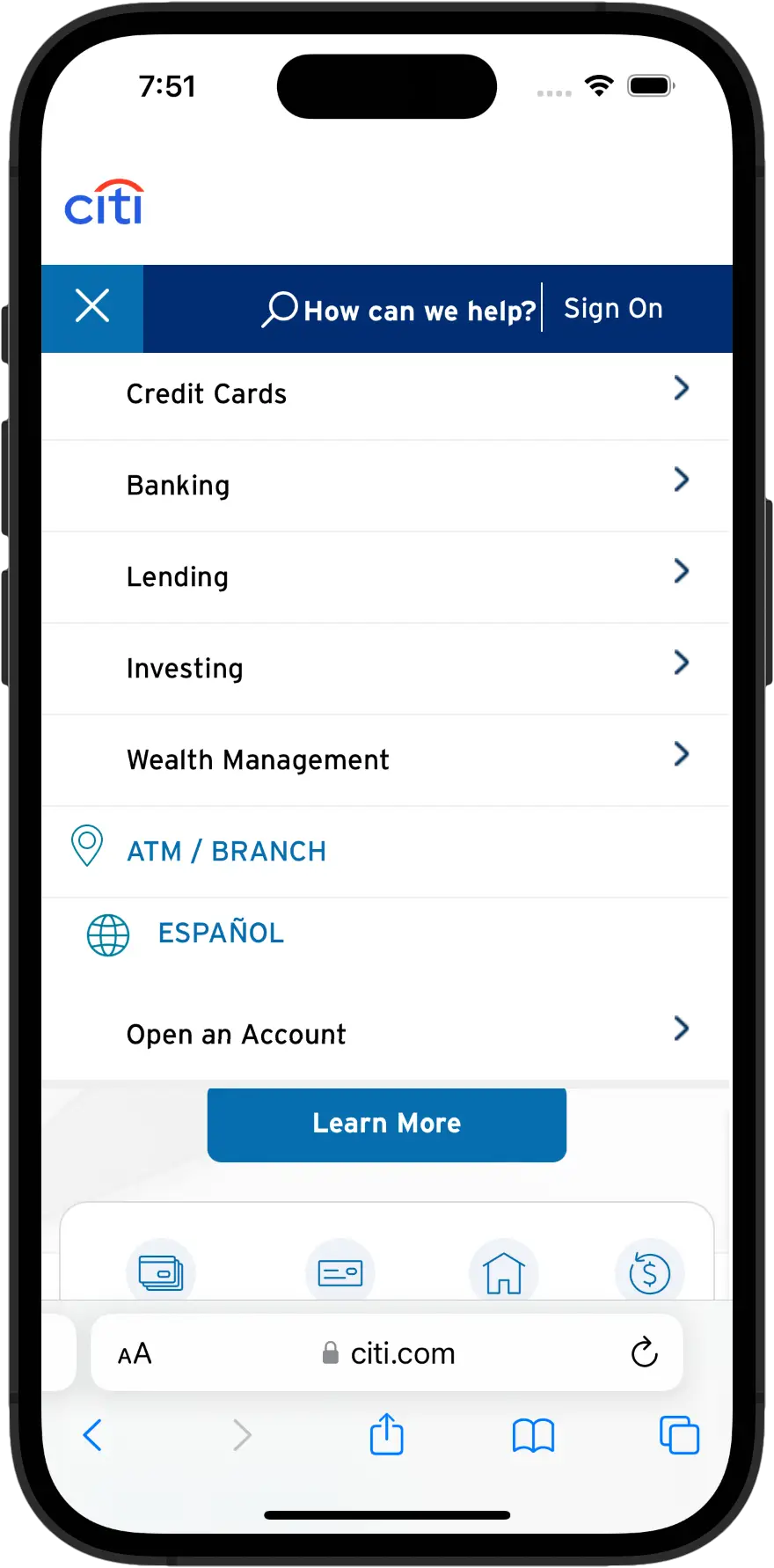

For example, consider the choices in a website’s navigation menu. They represent groups of related information. If they make sense, you’ll quickly find what you need. Conversely, if information isn’t organized logically, you’ll grow frustrated and leave.

Benefits of Information Architecture

Knowing how to organize information can help you personally. But IA is essential for product design — especially for complex products or those that offer lots of information. There are many ways IA benefits organizations:

- Improved User Experience (UX): Good information architecture allows users to navigate your website or app effortlessly, increasing user satisfaction and engagement.

- Increased Findability: A well-structured information architecture ensures content and features are easy to find and access, benefiting users and improving SEO.

- Scalability: Good information architecture allows digital systems to adapt to change, avoiding potential confusion as new features and content are added.

You know IA works when people find systems easy to use: they easily find what they’re looking for and get stuff done.

An Information Architecture Process

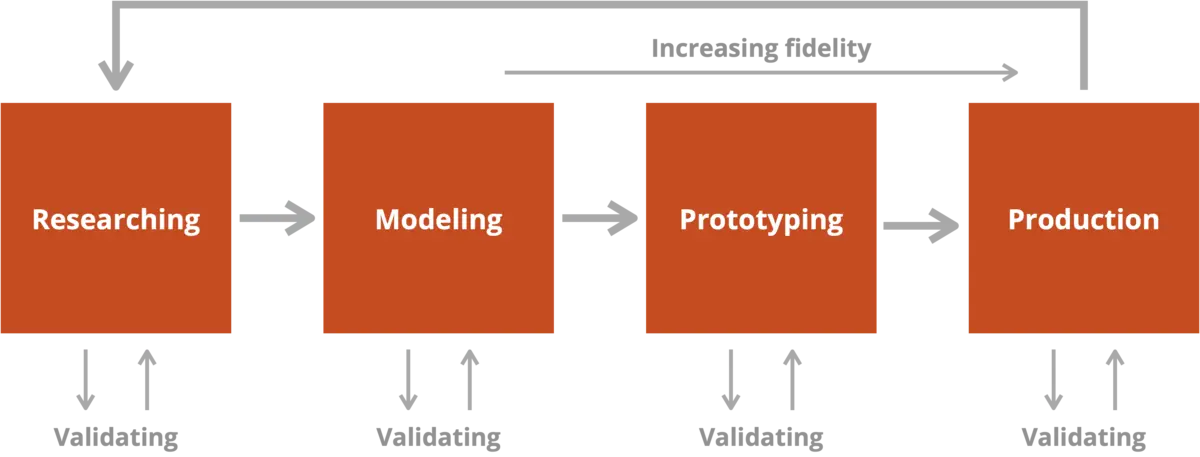

Effective information architecture doesn’t emerge organically; it must be designed. But that doesn’t mean the process is entirely top-down. At each stage, there are opportunities to validate directions and correct course.

Broadly speaking, the process has four sequential steps:

- Researching

- Modeling

- Prototyping

- Production

Let’s look at each step in more detail.

Information Architecture Research

Organizing information so it makes sense is easier said than done. For one thing, different people understand things differently. For another, some content will be unfamiliar: people don’t know how to think about it.

Because of this, designing effective information architectures starts with research. In particular, we want to learn about three areas:

- Content: Concepts the system must present to users so they can accomplish their tasks.

- Users: The mental models and conceptual understanding of the system’s intended audiences.

- Context: The environment surrounding the project, including motivations, competitors, regulations, infrastructure, etc.

Learning about user mental models is particularly tricky. Card sorts are a useful research method that allows you to uncover how people group particular sets of information.

Modeling

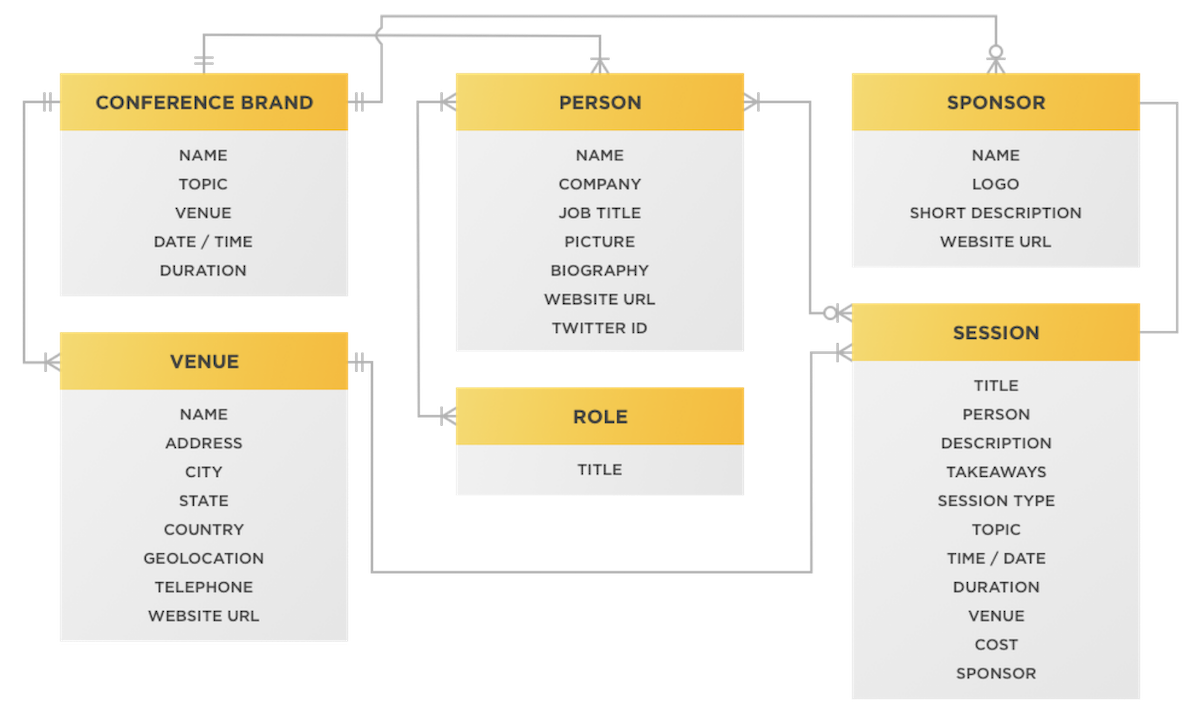

After understanding the project domain, the next step is developing models to explore how the system might be organized.

Models are diagrams that include key concepts and the relationships between them. Models allow teams to see the system’s “big picture,” including terminology and hierarchies.

Common models include:

- Concept models, which explore the overall structure of the system,

- Content models, which explore the attributes used to describe those concepts and the relationships between them, and

- Sitemaps, or tree diagrams, which describe the relationship of screens or pages in the system.

Sitemaps, in particular, are closely associated with information architecture. They have their uses, but keep in mind that most interactive systems aren’t strictly hierarchical.

During the modeling stage, you can validate directions by conducting Tree Tests, which allow you to test and refine proposed groupings and labels.

Prototyping

You can’t study the impact of an information architecture solely by looking at diagrams. Organizational structures must be expressed as things people can use. This is the role of prototypes.

Prototypes range from low-fidelity sketches to highly detailed interactive prototypes that accurately simulate the final product. Between these two are wireframes, which describe screen-level layouts without exploring visual design directions.

Each means of prototyping has its uses. But, overall, their most important use is validating and refining design directions by testing them with real users. One way to do that is by showing asking them to complete common tasks using prototypes.

Production

The process of designing an information architecture doesn’t end with prototypes. The ultimate point is to improve the systems users interact with. This requires that designs be moved to production — a step that can shift the design in various ways.

Ideally, you’ve learned about technological constraints (and opportunities) during the research phase. But it’s common to adjust designs as they meet the real-world conditions of production environments.

Producing an information architecture entails collaborating with people from several different disciplines. The earlier you can engage with production developers, the sooner you’ll deal with real-world conditions that will influence the design process.

And, of course, one of the benefits of putting systems into production is that you can start gleaning data on usage. Site analytics and search log files can provide valuable information for the following revisions to the system’s information architecture.

Strategy & Governance

Information architecture isn’t solely about organizing information. Categorizing information inevitably leads to strategic questions about how the organization will present itself and its offerings in the world.

Information architecture facilitates these discussions by making their implications tangible. It’s one thing to decide you’re going to divide your product portfolio into particular categories and another to see the impact of those decisions on your customers.

I'm increasingly realising that Information Architecture isn't just wireframes & taxonomy - it's really about answering fundamental questions about who you are as an organisation & how that aligns with user perceptions. It's a strategic exercise more than anything.

— Kat Excell (@KathrynExcell) April 20, 2021

Moreover, these questions are ongoing. New products and features come into the portfolio organically or through acquisition. Market conditions change. New competitors appear. IA must evolve to address these changing conditions, which requires developing bespoke governance frameworks.

See also:

- How Designers Can Help Bust Silos

- Internal and External Language

- Information Architecture as MacGuffin

- Finding Language/Market Fit

- Openness ↔ Control

- The Blind Spot in Digital Initiatives

- Two Approaches to Structure

- On Rules and Barbarism

- The Informed Life episode 58: Jesse James Garrett on Leadership and Information Architecture

- The Informed Life episode 11: Lisa Welchman on Governance

What’s With the Polar Bears?

Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville published Information Architecture for the World Wide Web in 1998. As with other O’Reilly books, this one featured an animal on the cover — in this case, a polar bear.

IA for the WWW quickly became the definitive book for people designing IA for complex websites. Perhaps because of its long title, practitioners started referring to it as the “polar bear book.” Polar bears have been the unofficial mascot of information architecture since then.

The definitive guide to IA — for the web and beyond.

Would you like to learn more about information architecture? My newsletter, which comes out every other Sunday, features short essays about the practice. My blog archives also have posts you may find useful.

Subscribe to my newsletter

Sent bi-weekly. I'll never share your address. Unsubscribe any time.