SALLAH: Indy, you have no time. If you still want the ark, it is being loaded onto a truck for Cairo.

INDIANA JONES: Truck? What truck?

This exchange from RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (1981) leads to one of the most thrilling car chases in movie history, in which our hero, Indiana Jones, fights his way onto the vehicle mentioned above. Onboard the truck is the Ark of the Covenant, which Nazis are trying to smuggle out of Egypt so their boss — Adolf Hitler — can use it to take over the world.

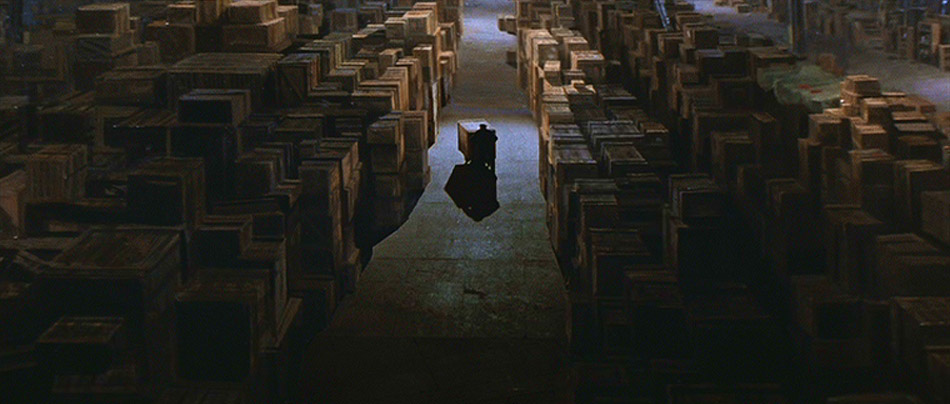

Sounds like a pretty important thing, right? Well, it isn’t. (Spoiler alert!) By the end of the movie, the crated ark is wheeled into a nondescript government warehouse packed with similar crates as far as the eye can see. The implication: this thing, which we’ve just spent a couple of hours obsessing about, will soon be forgotten — as it should be. You don’t want the audience to go home thinking about the implications of having something as powerful as the ark out and about in the world.

The soon-to-be-forgotten Ark of the Covenant being wheeled into its final resting place at the end of RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK. © Lucasfilm

The ark in RAIDERS is an excellent example of what’s known in the movies as a MacGuffin. I first learned about MacGuffins in Dan Hill’s excellent book Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary. Alfred Hitchcock originated the concept, and Dark Matter and Trojan Horses introduces it using Hitchcock’s own words:

A MacGuffin you see in most films about spies. It’s the thing that the spies are after. In the days of Rudyard Kipling, it would be the plans of the fort on the Khyber Pass. It would be the plans of an airplane engine, and the plans of an atom bomb, anything you like. It’s always called the thing the actors on the screen worry about but the audience don’t care… It is the mechanical element that usually crops up in any story.

In other words, the MacGuffin is the element that the story revolves around, the thing that everyone in the movie wants, that gets things moving. As such, it’s central to the film — but not because it matters in and of itself. Instead, it matters because it’s the catalyst that precipitates the story; an excuse for things to happen. By the end of the story, the MacGuffin can be done away with — carted off to oblivion, if possible.

I love the idea of MacGuffins because it gives a name to something important that I’ve experienced many times in my career: the object of a design project as a catalyst for a series of (often challenging) conversations about changes to an organization’s way of being in the world. Perhaps the market has changed, and the company must adapt or respond somehow. Maybe the company is introducing a new service, or one of its products is evolving into a platform.

Whatever aspect of the business is changing, these conversations are difficult because they deal with vague (and often conflicting) visions of the future. In these situations, stakeholders often find themselves having to act with too little information; perhaps even not going on much more than a hunch. They may feel threatened. Effecting change under such conditions can be ambiguous and confusing. Often, it’s also critically important — and sometimes, urgent too. What is needed is a way for stakeholders to have these discussions in a clear-headed way that eschews the political back-and-forth that characterizes business-as-usual.

I’ve often been in projects whose stated goal is to change or improve the navigation structure of websites. Most of these projects are precipitated by an important transformation the organization must undertake. For example, the business may be moving away from a product-centric model towards a service-centric one. The organization’s information environments are where customers come into contact with its offerings, so the definition of the new site structure becomes a catalyst for challenging conversations that will define more than its navigation systems.

Because it serves as the business’s front-end, the design of a website or app’s structures can be a proxy for the design of the business’s structures and how its components interoperate. In most cases, messing around with the design of a website is much less risky (and therefore less threatening) than messing around with the business itself. The website redesign project thus offers a safe space for stakeholders to hash out possible new directions for the company. It also allows them to validate the viability of these directions in tangible ways.

Such projects create tremendous value in two ways. First, and most obviously, they result in new navigation structures that offer a better fit with the business’s evolving context. Customers can find and understand things more easily and have a better grasp of how the organization can serve their needs. Secondly — and perhaps most importantly — such projects offer stakeholders a (relatively) non-threatening excuse to have critical discussions that will influence the direction of the business as a whole. The process of defining the information environment’s new organizational model precipitates conversations about the governance infrastructure that will make such a structure feasible.

The process of working through the information architecture could lead to a new navigation system that makes the company’s websites and apps easier to use. But the process could also reveal that the proposed new direction isn’t viable. In the latter case, the “design” generated by the project may be shelved to allow the team to move on to the next adventure, much as the Ark of the Covenant was shelved at the end of RAIDERS. But that doesn’t mean it was without value. In fact, the journey will have invariably revealed insights that will allow stakeholders to act with greater clarity and confidence as they embark in future explorations.