Fast, sudden change can make it hard to understand what’s happening in a complex situation. Your attention focuses on a few salient facts — if you can pick them out from the noise. But even those facts aren’t very useful unless you dive deeper. Fortunately, systems thinking provides a tool for doing just that. I’ll introduce it by unpacking the recent turmoil at OpenAI.

OpenAI is arguably the most important company in tech today. Their ChatGPT is the fastest-growing product in history: just two months after launch, it already had 100 million active users. It’s no accident: ChatGPT brought LLMs — the most transformative new technology in decades — to the masses. From the outside, it seems as though the company has executed flawlessly. As recently as November 6, it announced an exciting slate of improvements. And yet, less than two weeks later, OpenAI almost imploded.

If you follow tech, you’ve likely seen the story. (If not, here’s an excellent primer.) TL; DR: on November 17, OpenAI’s board fired the company’s popular CEO, Sam Altman — an unexpected move that led to unrest among staff (95% threatened to resign) and OpenAI’s primary partner, Microsoft. After a few days, Altman returned as CEO under a new board. The power struggle played out in public, with a few actors — and thousands of bystanders — posting on X.

As someone interested in AI (and an OpenAI customer,) I followed the evolving situation with trepidation. Something became apparent early on: chatter included a lot of noise. (Lao Tzu: “Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.”) More to the point, people jumped to conclusions based on a few facts. Social media amplifies scoops regardless of their veracity.

To understand what’s going on, you must dive deeper. This requires two things:

- Waiting for relevant facts to emerge, and

- A framework for deriving meaning from those facts.

In the rest of this post, I’ll introduce you to such a framework — the Iceberg Model — and explain the OpenAI situation through that lens.

The Iceberg Model

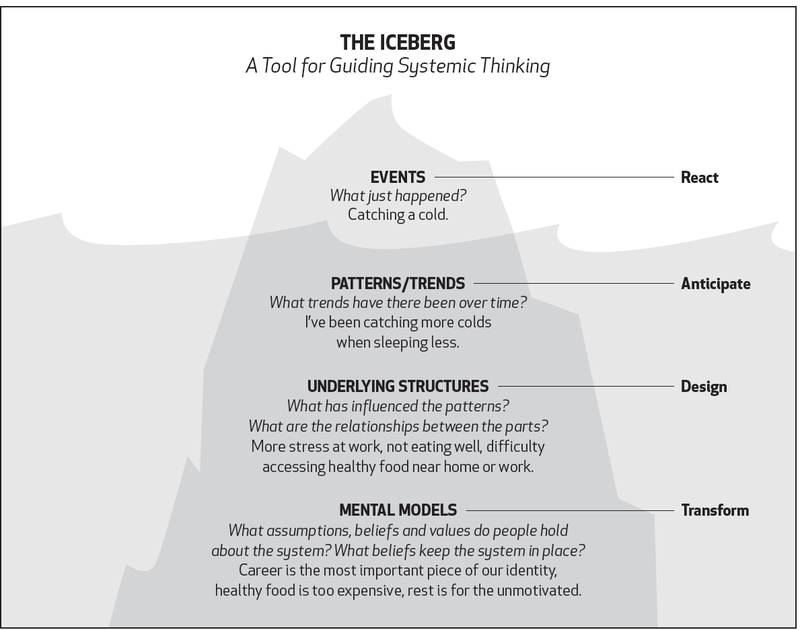

Many systems, including companies, manifest complex behaviors. The Iceberg Model explains the different levels at which you can understand such a system:

- Events

- Patterns

- Structures

- Mental models

The framework uses the iceberg metaphor because we only tend to see what happened — the first level. Levels 2-4 operate “beneath the surface,” influencing the stuff that’s more easily visible. As a result, we focus on things that are more immediately apparent without giving as much attention to their underlying causes. Alas, that’s where changes have most impact. Let’s look at all four levels more closely.

Events

Events refers to the immediate occurrences that are most obviously visible. These are the latest facts you can ascertain about the system or situation, the sort of thing you read about on X or in the news. (Of course, you must carefully distinguish opinions from facts.)

The OpenAI story features a quick sequence of events: the (apparently) successful product announcements, the blog post announcing the leadership change, a series of X posts from the CEO, former board chair, employees, partners, etc.

These events are important data points on their own. But they don’t tell the whole story. For that, you must take in a broader time frame. That’s where patterns come in.

Patterns

Patterns refers to trends or patterns of events that unfold over time. By looking at more relevant data points going as far back as possible, you start perceiving things that come up over and over again.

In OpenAI’s case, the November 6 product announcements were the latest in a series of commercial offerings, starting with the GPT-3 API in 2020, followed by DALL-E in 2021 and ChatGPT in 2022. These product launches are significant because OpenAI was founded in 2015 as a non-profit research company aimed at advancing the state of AI without needing to generate financial returns. And yet, its offerings since 2020 increasingly look like commercial tech products.

The company’s founders and principals have also shared thoughts via interviews, lectures, and posts going back many years. Reviewing these posts reveals evolving positions about the company’s aspirations and strategy.

Which is to say, the events of the last couple of weeks aren’t isolated incidents. Seen in a broader context, they reveal trends resulting from specific organizational structures that have set OpenAI on its current trajectory.

Structures

In this case, by structures we mean OpenAI’s organizational groupings, hierarchies, rules, procedures, etc. At a minimum, the company has a (seemingly) typical corporate structure: a board, management that reports to the board, and staff that reports to management.

But digging deeper, you learn OpenAI’s structure is somewhat rare. Remember, its founders want the company to be a non-profit, constraining its ability to raise capital. But developing AI requires lots of computing and human resources, which takes massive capital infusions.

To address this dilemma, in 2019 the company created a “capped-profit” company controlled by the non-profit. Ideally, this structure allows OpenAI to raise capital and establish commercial partnerships to build the necessary infrastructure and recruit employees while preserving its non-commercial ethos. (See this Bloomberg article for details.)

It sounds like a case of wanting to eat the cake and have it too. Much of the disruption we saw in the last two weeks stems from this unusual structural choice. But that structure didn’t emerge arbitrarily.

Mental Models

This brings us to the deepest layer of the iceberg: mental models. Mental models are the beliefs, values, and assumptions that influence the structures, patterns, and events we perceive. As we go down the layers, things become more abstract — and this is the most abstract layer. Which is to say, analyzing mental models requires reading between the lines.

OpenAI’s situation seems shaped by two mental models. One posits that only a for-profit company can acquire the infrastructure and talent needed to achieve its goal of developing AI. The other posits that developing AI beneficially requires non-commercial approaches.

To wit, this is how the company (still) introduces itself:

OpenAI is a non-profit artificial intelligence research company. Our goal is to advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return. Since our research is free from financial obligations, we can better focus on a positive human impact.

Underlying these two models are divergent beliefs about ideal economic and social arrangements. Someone who distrusts capitalism for ideological reasons might push for the non-commercial structure, while a more pragmatic manager might be open to the for-profit approach.

There are also questions about what “benefit humanity” means. For some, it might mean raising living standards by making products better and cheaper, requiring competition and quick iteration. For others, it might mean developing products aligned with broader social interests, necessitating a slower pace.

These two models are at odds, and they’re likely not the only ones pulling the organization in different directions. It’s tough to resolve these tensions within one structure. Once you understand these ideological rifts, and the weird structure they’ve produced, the events of the last couple of weeks make more sense.

What This Means for You

Since you likely do not influence OpenAI, this discussion is academic. But this framework applies to any complex system, including your own organization, a project you’re working on, or even your day-to-day life.

Knowing that the events that catch your attention – those you witness or hear about in the news — result from underlying issues and structural constraints helps you understand them more deeply. And suppose they’re things you can do something about. In that case, you’ll be more likely to focus on root causes rather than symptoms, leading to greater leverage.

Examining your behaviors through this framework can help you get down to root beliefs and values. If you’re not getting the desired results, consider what structures enabled those results — and, more importantly, what mental models formed those structures. Ultimately, design is about change. And as George Bernard Shaw said, “Progress is impossible without change; and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.”

A version of this post first appeared in my newsletter. Subscribe to receive posts like this in your inbox every other Sunday.