Information architecture is about designing semantic places that allow people (and other agents) to find and understand stuff. I realize this definition is a mouthful. I won’t unpack the “other agents” bit here, although it’s important. Instead, let’s delve into the phrase “semantic places.”

Your house or apartment is an intentional physical context; it’s a place that’s been (literally) walled off from the rest of the environment to keep you safe and warm. The walls bound the place: besides offering shelter, they clearly distinguish between “inside” and “outside.” You behave differently when you’re in one or the other.

We do something similar with digital systems such as websites and apps. Rather than walls, such systems are bounded by language. In particular, the words and symbols in navigation structures give us a sense of what we should (and shouldn’t) expect to do and find there.

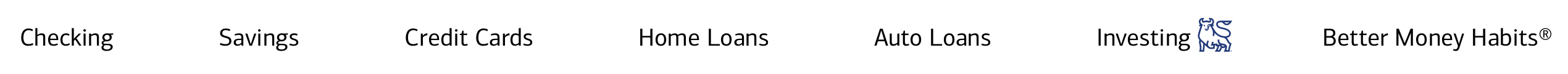

Consider this navigation bar:

You don’t need to read the company’s name to know this is a bank. The words on the navbar suggest that context to your mind. As with physical contexts, you have expectations about what you can find and do here. For well-known institutions such as banks, those expectations are culturally conditioned.

When designing a navigation system, you want to tap these expectations; you can make a website or app easier to learn if you leverage what users already know. For example, people expect banks to offer financial services, so the navbar can include words like “checking” and “savings” without explicitly calling them out as services.

Navigation is central to how people understand the place. But they also experience IA in other aspects of the system. For example, in content-heavy systems such as websites, page titles and section headers also show key terms that help establish the place’s bounds. Titles, headers, and navigation options are manifestations of intentional semantic structures that create contexts in peoples’ minds.

Effective information architectures don’t emerge organically; they’re designed. There are three concepts you must understand to create an IA: distinctions, relationships, and patterns. They’re closely related, but are worth examining independently.

Distinctions

Distinctions are meaningful conceptual differences between related items. They bring to mind the phrase “differences that make a difference,” which is the title of a book by Russ Ackoff1. When you offer two or more options (e.g., in a navigation menu), you want people to understand what to expect when they pick one over the other. When designing an IA, we want to amplify the contrast between terms so that distinctions are clear.

Relationships

Each option stands on its own as a unit of meaning, but its meaning might shift when shown next to other options. Consider the word “checking”: on its own, it might mean one of several things. But when displayed next to the word “savings,” we immediately consider how “checking” and “savings” might relate.

When we see these terms together, our mind goes to finance, a domain where there’s a meaningful distinction between “checking” and “savings.” We have various means to create such relationships. In this case, the relationship is suggested by the proximity of the two terms on the screen, identical typographic treatments, etc.

Patterns

In larger sets of distinct yet related items, our minds spot patterns: recurrent arrangements that suggest subsets of items within a larger whole. In an information architecture, they might consist of groups of terms that hint at conceptual similarities. They could also be suggested formally by the length or format of phrases and words that comprise the set.

I spot several patterns in the navigation bar shown above. The first six elements, which consist of either one- or two-word labels, describe standard financial services such as checking, savings, and investing. The last element in this set is different: “Better Money Habits®” suggests educational content. The label includes a registered trademark symbol, which the others don’t, suggesting this might be proprietary content.

Another pattern is suggested by the two terms in the middle, “Home Loans” and “Auto Loans.” The presence of the word loans in both labels suggests a special relationship between these two items. Again, our mind gravitates to the distinctions between them, which in this case are carried by the other words in both phrases, home and auto.

Note that both home and auto are common words we often use without considering them in the financial services context. But here, among these other terms, they’re used to amplify distinctions between choices by relating them to other key words and each other.

Every term we introduce to the set can shift the meaning of the whole. Designing such structures can feel like a semantic game of Tetris: you want to identify the correct term to suggest a particular idea while also fitting in with the rest of the set while creating a coherent whole.

In designing an IA, you want to create intentional relationships between intentionally distinct terms. People who encounter such structures will perceive patterns, either between adjacent concepts or with other concepts they already understand. These patterns establish contexts that allow people to know where they are and what they can do and find there.

Distinctions, relationships, and patterns enable us to draw mental bounds around conceptual domains. They’re how we understand semantic places. As such, they’re foundational IA concepts.

-

Amazon links on this page are affiliate links. I get a small commission if you make a purchase after following these links. ↩