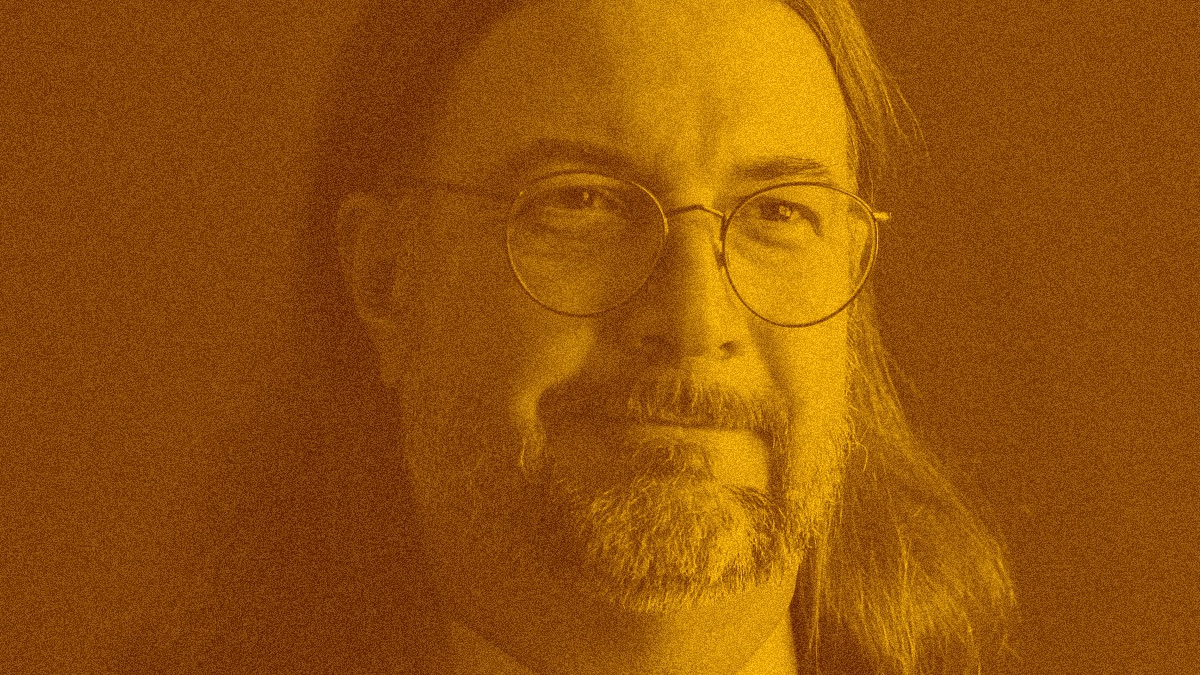

Episode 117 of The Informed Life podcast features the second part of my conversation with Bob Kasenchak about music and information architecture. As you may recall, part 1 (ep. 116), dealt with the structure of music — that is, music as an information medium. The second part deals with the information we use to categorize music — i.e., metadata.

Metadata and categorization schemes are central to the work of information architecture, and music offers lots of examples and edge cases. As Bob put it,

Free text search just isn’t going to do it. You have to have clean, good, standardized, consistent metadata attached to things, which means we have to agree on what artists’ names canonical versions are, and have alternate versions encoded. We have to agree on what genres are, which is a whole conversation we could probably have… or at least pick a lane and stick to it as to what genres are so that we can try and find what we’re looking for.

In the era of mass-produced recordings, there’s a common taxonomy that describes musical works: there are

- Genres

- Artists working within them

- Albums released by artists

- Songs contained in albums

Of course, even within basic pop music there are edge cases that test the models. Some artists’ works span several genres. Artists can change their names (sometimes, as in the case of Prince, to unpronounceable glyphs,) multiple albums by the same artist can have the same name (e.g., the first four Peter Gabriel albums.) As Bob explained, these edge cases define the model in some ways.

But even considering such complications, not every genre is as simple as pop. Classical music, in particular, entails lots of other considerations. For example, a works’ composer can be more important than it’s performer and ‘performer’ itself isn’t a clear-cut construct: do you mean the conductor, orchestra, soloist, or a combination thereof? Some performers (e.g., Glenn Gould) record the same work by the same composer, at which point the year of recording becomes the most significant bit.

Which is to say, the IA required to properly describe (and make findable) classical music is more complex than that needed for pop music — even when considering pop’s edge cases. I contend this is why Apple released a dedicated app just for classical. (As we noted in the show, Apple Music Classical wasn’t the first of its kind, and was in fact an acquisition.)

The existence of this app is what prompted this conversation with Bob, and spent some time discussing the reasoning and import behind it — particularly, in a world where new technologies such as AI can potentially describe information to make it more findable. We spent some time during the show discussing potential uses of LLMs for information architecture — mostly a speculative prospect at some point, but one with real potential.

Even though music might seem like a niche subject, many of the issues we discussed in this conversation apply to other areas as well. If your work entails designing digital information systems of any kind, it behooves you to check them out — these are two of the most IA-centric conversations we’ve had on the show so far.

The Informed Life episode 117: Bob Kasenchak on Music, part 2