A version of this post first appeared in my newsletter. Subscribe to receive posts like this in your inbox every other Sunday.

Metadata is essential to effective digital products. And yet, many designers struggle with the subject — unsurprisingly, since it can be pretty abstract. But getting a grip on metadata is essential, especially if you design digital products or publications.

In complex information systems, metadata allows people to find stuff. Consider locating a book in a library. The book (i.e., its contents) is what you care about — the “data.” In contrast, the book’s title, author, publisher, year of publication, ISBN, and call number are attributes that describe the data — “meta-data” — so you can locate it among all the others stored in the library.

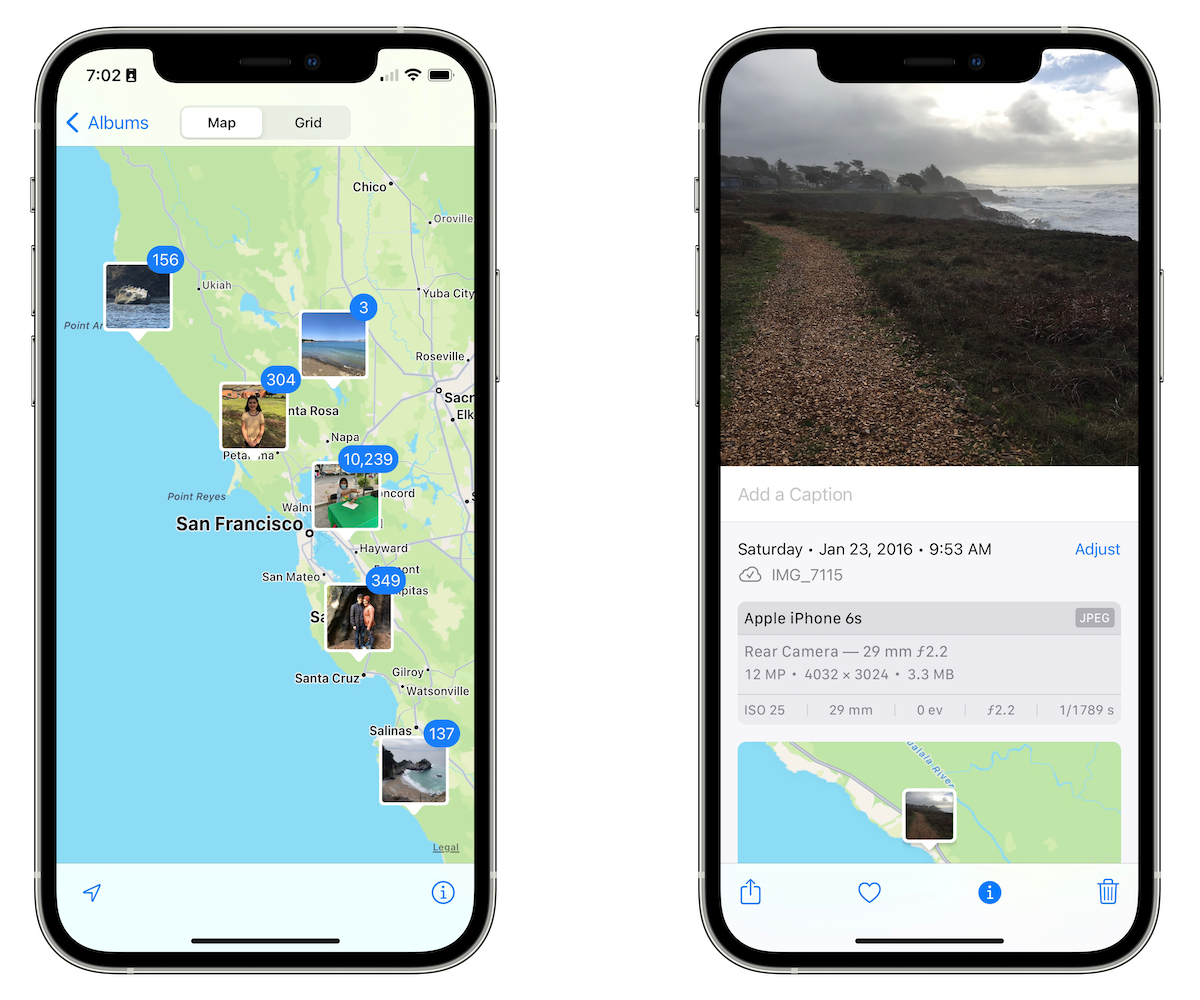

While you can read the author’s name on the book’s spine, metadata is often invisible to users. For example, your phone’s camera can save the coordinates of the location where you took a picture. The location doesn’t show up as part of the picture (i.e., the sequence of pixels that displays the image.) However, you can find the photo later by using a map view or a search box.

The picture, like the book, is the thing you care about. Its geographic location, the date and time, and details about the lens are all attributes that describe the thing — but not the main attraction. However, that doesn’t mean they’re not important. The value of good metadata is evident if you have an extensive library or a large photo collection.

What does “good” metadata look like? For one thing, it matches users’ mental models. Time and location are good attributes for photos since we know pictures are taken at a particular time and place. When looking for an old photo, we often consider where and when it happened as search criteria.

Which attributes should be considered data, and which metadata? It depends on the context and the needs of the user. For example, in a “normal” photo album app, details about lenses might be considered metadata. But if you’re designing an app that helps users identify which lens they’ve used most, lens data might be the main attraction.

I said metadata is often invisible to users. Much metadata indeed describes things behind the scenes. But users can often see the effects of metadata in the system. For example, the photo album’s map view manifests the geolocation metadata that describes each picture. When users see the map, they know the phone must capture location data in each snapshot — even if they don’t know how to access it directly.

That said, some metadata is directly accessible to users. For example, in the iOS Photos app, you can swipe up any picture to see some of its metadata. You can edit some of it, including the time and location, names of people who appear in the image, and a caption. You can also mark an image as a favorite. These are all information about the picture — not the picture itself. (If you were to crop or add a filter to the image, you’d be editing its data, not its metadata.)

One of the challenges in understanding this concept is that digital blurs the difference between data and metadata, making it harder to distinguish between the two. For example, in old libraries, metadata about books was stored in a dedicated physical location: the card catalog. You’d go to this repository to find pointers to the places within the library where you could find the data you needed. Compare this with finding a book on the Kindle: you interact with the book’s descriptors in the same “place” where you see its text.

But hard as it may be, designers need to understand the difference between data and metadata. Again, it comes down to focus: data is what users care about in the system; metadata lets them find and use it. In most cases, metadata shouldn’t be the main attraction. But you should still think about metadata, since it allows you to express what matters most to users and how they’ll best find it.