The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload

By Daniel J. Levitin

Dutton, 2014

I’ve previously shared notes about books I’ve read on this website. Recently, I tried sharing my notes on Twitter as I read (on in this case, re-read) a book. To make these notes easier to reference, I’ve pasted the resulting thread below. (With minor tweaks for easier reading.)

The book in question is Daniel Levitin’s The Organized Mind. I first read this book a few years ago. I’ve learned more about this subject since then and am revisiting it as a (hopefully) better reader.

So, what’s “The Organized Mind” about? The back cover promises neuroscience-backed suggestions for navigating “the age of information overload.” Information overload leads to sub-optimal performance (e.g., misplaced car keys, missed appointments, exhaustion, etc.) — but “small, simple, yet consequential changes” can help.

The book is divided into three parts. Going by the TOC:

- Part 1 explains information overload and how our minds work

- Part 2 offers practical advice for organizing various areas of our lives

- Part 3 looks to the future and discusses junk drawers

Intriguing.

Introduction

The introduction sets the context by tracing the evolution of human neural enhancement and how it’s helped us interact with each other and our environments more skillfully. One way we do this is by organizing (i.e., categorizing) aspects of our experience. Categorization is innate. E.g., “Most mammals are biologically programmed to put their digestive waste away from where they eat and sleep.” 👀💩

Our capacity for paying attention is limited and memory is unreliable. So, another way we enhance our minds is by offloading cognitive tasks to the environment. (E.g., through writing.) Grokking how the mind categorizes things + how we manifest those categories in the world can help us be more effective.

The cognitive neuroscience of memory and attention — our improved understanding of the brain, its evolution and limitations — can help us to better cope with a world in which more and more of us feel we’re running fast just to stand still. (p. XXV)

Now onto part 1 of the book…

Chapter 1: Too Much Information, Too Many Decisions — The Inside History of Cognitive Overload

The gist: our current contexts (social, material, economic, etc.) tax our ability to pay attention and make decisions. Categorizing things allows us to cope.

Neuroscientists have discovered that unproductivity and loss of drive can result from decision overload. Although most of us have no trouble ranking the importance of decisions when asked to do so, our brains don’t automatically do this. (p. 5)

“The decision-making network in our brain doesn’t prioritize.” (p. 6) I.e., deciding what to focus on and what to do isn’t something the mind does on its own; it takes effort on our part. Attention is an essential resource, since it determines what we focus on.

“Highly successful persons” delegate the narrowing of their attentional filters — i.e, they find other means (e.g., assistants) to pre-focus for them. Change and importance are two principles our minds use to filter our attention. We’re good at detecting changes. Importance isn’t merely objective, but personal. (E.g., you overhear your name spoken in a crowded room.)

Due to the attentional filter, we end up experiencing a great deal of the world on autopilot, not registering the complexities, nuances, and often the beauty of what is right in front of us. (p. 11)

Thus, we must hone our ability to detect change and importance. The chapter traces information overload throughout human history. Although the context has changed, many of the same challenges remain. (I wrote in my notes, “same as it ever was” — and shortly after, Levitin cited the Talking Heads song. 😜 )

Another principle of our attentional system: switching our attention carries a high cost. The chapter offers a brief explanation of what happens in our nervous system when something catches our attention. This is especially challenging since our context is asking that we do more stuff. E.g., we used to delegate travel arrangements to travel agents, but now mostly do it ourselves. Levitin calls this “shadow work.”

We also must deal with more information than before. We must become more discriminating in what we let into our attention. Again, this is costly. A passage that resonates:

Conflicting viewpoints are more readily available than ever, and in many cases they are disseminated by people with no regard for facts or truth. (p. 20)

We are subject to cognitive biases. (Levitin was a student of Tversky’s.)

By analogy to visual illusions, we are prone to cognitive illusions when we try to make decisions, and our brains take decision-making shortcuts. (p. 22)

The chapter offers an overview of the evolution of mental categorization. Emphasis on the role of tracking social relations (especially kinship) in humans and parsing of things we encounter in the environment.

“Functional categories” are informal and heterogeneous yet reflect our experience of reality. (E.g., the category “bugs” includes several species that are “biologically and taxonomically quite distinct.” It helps to shift the burden of triaging from our minds to the external world. An overview of Gibsonian affordances.

The organized mind creates affordances and categories that allow for low-effort navigation through the world of car keys, cell phones, and hundreds of daily details, and it also will help us make our way through the twenty-first century world of ideas. (p. 36)

Chapter 2: The First Things to Get Straight — How Attention and Memory Work

The mind operates in one of two modes: the “default” mode, when the brain is at rest, and a stay-on-task mode researchers call “the central executive.” The mind switches between them like a see-saw. Recent research has given us insights into the neurochemistry of how this works.

The way our memory works is amazing. The nervous system functions like a network where a very large number of memories are encoded. Due to its complexity, remembering can be imperfect. Our brains sift through competing instances of what we’re trying to remember. Memory is also affected by emotions. As a result, memory is fallible.

We categorize things for “cognitive economy.” E.g.,

Why is it that when you think of hash browns, your brain doesn’t automatically deliver up every single time you’ve had hash browns? It’s because the brain organizes similar memories into categorical bundles. (p. 56)

Eleanor Rosch’s concept of basic-level categories: rather than deal with specifics of whatever we’re observing, we refer to more generic representatives of the set. (This reminded me of Hayakawa’s ladder of abstraction.)

Fuzzy categories: often, there aren’t hard boundaries around categories. Cf., Wittgenstein’s “family resemblances.” The book uses Labov’s cups as an example.

These complex mental mechanisms have served us well. But in this time of information overload, we must extend our thinking outside the body by using aids such as index cards to externalize our thinking.

On to part two of the book.

Chapter 3: Organizing Our Homes — Where Things Can Start to Get Better

Messy houses are a modern problem. People didn’t use to have as much stuff as we do. Organizing stuff so we can find it later can be challenging.

We can learn from people who organize other complex physical environments. E.g., Ace Hardware stores are organized into departments (plumbing, electrical, paint, etc.), but you can find hammers alongside nails because people who need nails likely need hammers.

The neuroscience of how we remember the location of things is understood. The hippocampus plays a major role and it’s been shown to be enlarged in people whose work relies on memory, such as London cabbies.

Cognitive prosthetics:

Simple affordances for the objects of our lives can rapidly ease the mental burden of trying to keep track of where they are, and make keeping them in place… aesthetically and emotionally pleasing. (p. 83)

That is, our environments can remind us of things. E.g., if you read a report about rain the next day, lean an umbrella on the door the night before. (I’m wondering how this might translate, if it does, to information environments.)

We can also be mindful of how we group things when storing them. “The more carefully constructed your categories, the more organized is your environment and, in turn, your mind.” (p. 87) We should limit such categories to (at most) four types of things.

Three organization rules (p. 90):

- A mislabeled item or location is worse than an unlabeled item

- If there’s an existing standard, use it

- Don’t keep what you can’t use

When working digitally, aim to create different workspaces for different kinds of work. Levitin goes as far as suggesting we use different devices for different tasks. (While acknowledging this might not be feasible for many.)

This resonates with me. We don’t usually think about the differences between the things we do with digital devices and how making everything available at once can distract us. It’s why I find the Focus feature on iOS/iPadOS so interesting.

Today I got to play around a bit with the Focus feature on iOS 15 and iPadOS 15. It's very cool. https://t.co/YUlhLZMDxg

— Jorge Arango (@jarango) February 5, 2022

The opportunity to multitask is detrimental to cognition. (I.e., it’s not just multitasking itself that’s bad — the mere possibility of multitasking can affect us.) Bottom line: We can be more intentional with how we offload our memories to the environment and how we structure the environment to help us manage our attention. This includes grouping things mindfully and getting rid of clutter.

Chapter 4: Organizing Our Social World — How Humans Connect Now.

Key: ours is a highly social species. Our innate ability to categorize extends to our social relations. Among other things, this manifests in crowdsourcing, which is a kind of sensemaking at scale. But the crowd isn’t always right.

Creationists crowd cyberspace every bit as effectively as evolutionists, and extend their minds just as fully. Our trouble is not the overall a sense of smartness but the intractable power of pure stupidity. (Adam Glopnik, cited in p. 120)

We know many more people than our ancestors did. Today, we meet our mates through software and understand intimacy differently than our forebears. Organizing our myriad social relations is hard, but we can turn to tools for help.

Other people can help extend our memory. “Transactive memory” is how we remember through others. But interactions with others often aren’t straightforward. People can lie outright or subtly imply what they want from us. Philosopher Paul Grice calls the latter “implicatures.” He proposes maxims for cooperative speech acts. They involve:

- Quantity

- Quality

- Manner

- Relation

Quoting from p. 139:

Quantity. Make your contribution to the conversation as informative as required. Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.

Quality. Do not say what you believe to be false. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.

Manner. Avoid obscurity of expression (don’t use words that your intended hearer doesn’t know.) Avoid ambiguity. Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity). Be orderly.

Relation. Make your contribution relevant.

(Can we pause here to appreciate the delicious irony of using the word “prolixity” in this context?)

(I’ve quoted these maxims in full because I found them especially useful. They reminded me of the Buddhist precept of “right speech.”)

Due to the complexity of social relations, we are subject to biases that arise as we try to understand the world through our position vis-a-vis other people. This includes the pervasive (and pernicious!) in-group/out-group bias.

Bottom line: Our social relations are subject to categorization — and to categorization errors. We must be mindful, since “We are all increasingly interconnected, and our happiness and well-being are increasingly interconnected.” (p. 159)

Chapter 5: Organizing Our Time — What Is the Mystery?

The gist: our brains regulate our experience of how events unfold over time, including the sequence in which events happen (or how we expect them to happen.) Conversely, how we use our time affects our brains. ⌛️🧠

Because our perception of how things unfold over time depends on the brain, its functioning affects how we experience things. E.g., people with damage to the prefrontal cortex might lose the ability to plan ahead. The prefrontal cortex also determines impulse control. “What all this points to is that good time management should mean organizing our time in a way that maximizes brain efficiency.” (p. 169)

The converse is also true: there are physiological benefits to organizing our time. (E.g., avoiding multitasking.) Effectiveness calls for constantly switching our focus between doing and monitoring what we’re doing. Some people do this better than others.

This constant back-and-forth is one of the most metabolism-consuming things that our brain can do. (p. 174)

Another key balance: staying on task vs. flexible thinking. Again, effectiveness calls for switching between them. People with damage to the frontal lobe can’t easily integrate new conditions and rules. (I.e., they stay on-task even when there’s a need to change.)

As we do with things in physical environments, we group experiences into chunks. This explains our ability to understand film cuts, which baffle people who haven’t grown up with cinema. We read into situations, filling in the blanks for implied previous or next steps.

A key to understanding our experiences in time is sleep, which helps us process info via:

- Unitization: combining experience chunks into unified concepts

- Assimilation: integrating new info into existing knowledge

- Abstraction: discovering and integrating “hidden rules”

The discussion of sleep in this chapter is fascinating. Did you know our natural sleep cycle is bimodal? Left to our own devices, humans sleep for 4-5 hrs, wake for 1+ hrs, and then sleep again for 4-5 hrs. This might have evolved as a way to help us ward off predators at night.

(I’m considering trying this rhythm, although with shortened sleep periods. Maybe 3 hrs sleep + 2 hrs awake + 3 hrs sleep? Two hours of quiet writing time in the middle of the night sounds appealing.)

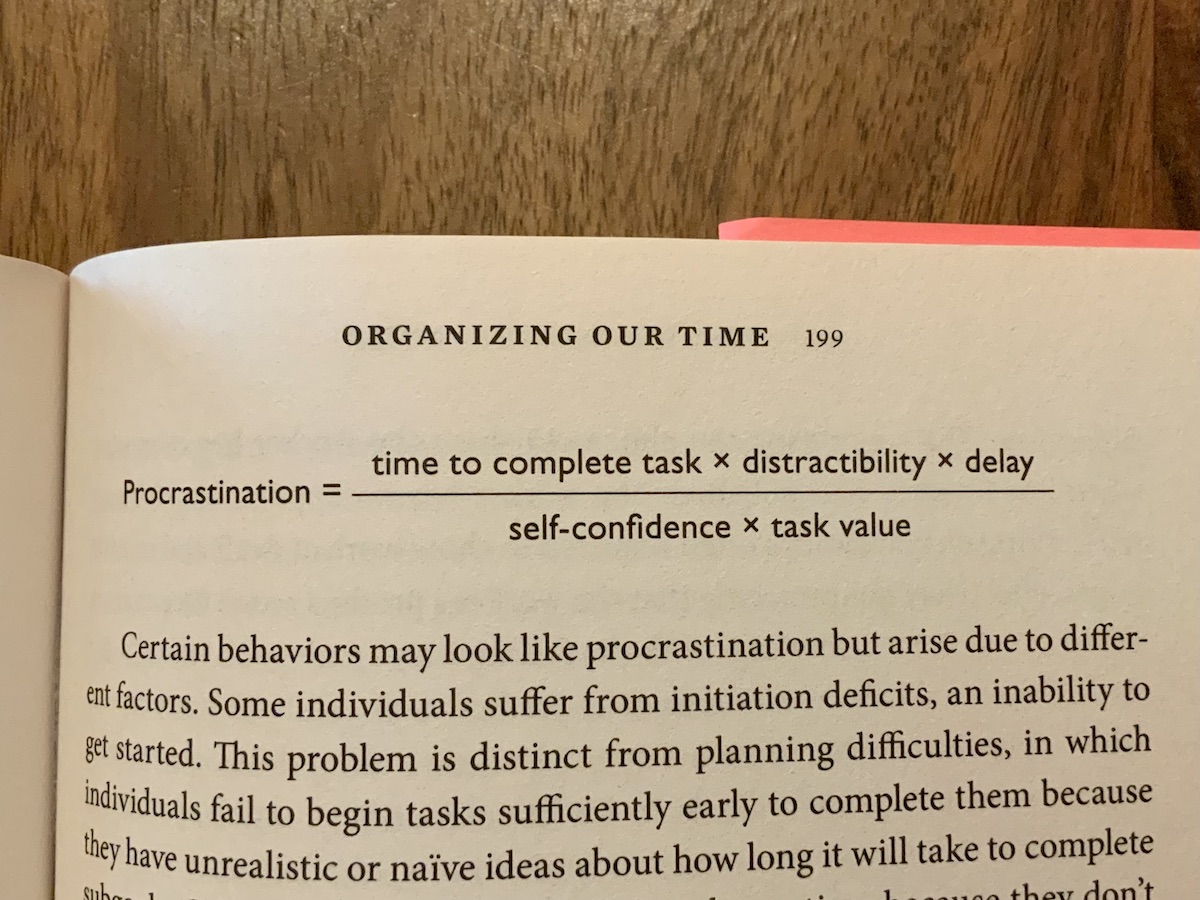

Another time-related issue: procrastination. Why does it happen? Again, the nervous system plays a key role. Levitin offers a formula for the contributing factors. (It’s evolved from the work of Piers Steel, “one of the world’s foremost authorities on procrastination.”

Conversely, how do we create new things? By entering a state of flow. (Cue Csikzsentmihalyi.) Again, our nervous system plays an essential role. We should aim to switch between states of relaxation and focus.

Anything that tempts us to break the extended concentration required to perform well on challenging tasks is a potential barrier to success. (p. 209)

See also Cal Newport’s work. (BTW, Newport was recently on Tim Ferris’s podcast; worth your attention.)

Our experience of time changes as we age. We should aim to remain mentally active to avoid the negative effects of aging. This reinforces this chapter’s gist: our brain affects our experience of time and how we manage time affects the brain.

Chapter 6: Organizing Information for the Hardest Decisions — When Life Is on the Line

Gist: how to make hard choices given imperfect information. Specifically, this chapter discusses medical choices — but the methods covered apply to other domains as well. We want to make “the best decisions possible.” Going with our guts might serve us in some situations, but in others, we need to understand probabilities. Specifically, this chapter covers Bayesian reasoning.

Love this:

The cliché in medical diagnostics is ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.’ In other words, don’t ignore the base rate of what is most likely, given the symptoms. (p. 228)

The representativeness heuristic.

This chapter features an extensive description of contingency tables, a simple tool to help us make decisions (at least those for which we have data) through a Bayesian lens. I can’t do the concept justice in a few lines, but it’s worth checking out.

In healthcare, Bayesian reasoning can have life-or-death implications. Alas, many mainstream doctors often don’t see through a probabilistic lens. That said, alternative medicine is worse since it doesn’t consider statistical evidence at all.

Framing and other biases keep us from making statistically-informed decisions. (Citing Kahneman.)

The other chapters in this book have been particularly concerned with attention and memory, but the great boon to making decisions about thinks that matter is mathematics (p. 266)

Chapter 7: Organizing the Business World — How We Create Value

The gist: to create value at scale, we need organization — both of people and information. Before the Industrial Revolution, enterprises were artisanal and small. Industrialization increased scale and reach. Managing complex enterprises (e.g., railroads) required different organizational structures, documentation, standards, etc. All of this brought complexity.

People dealt with increasing complexity through novel ways of organizing enterprises and the information that enabled them. (E.g., hierarchical org structures, filing cabinets.)

Companies can be thought of as transactive memory systems. Part of the art of fitting into a company as a new employee, indeed part of becoming an effective employee (especially in upper management), is learning who holds what knowledge. (p. 273)

People make decisions within such systems and decisions are influenced by (among other things) emotions and the degree of trust between participants. Managers and leaders must delegate. Ethics — which are driven by our nature — inform decision-making.

U.S. Army management principles (p. 285):

- Build cohesive teams through mutual trust

- Create shared understanding

- Provide a clear and concise set of expectations and goals

- Accept prudent risks

A critical factor for leadership: locus of control (“how people view their autonomy and agency in the world”). People with internal locus accept responsibility for outcomes. People without it attribute what happened to external conditions or “luck”. (My take: our beliefs about agency affect the course of our lives. Beware the victim mindset — in yourself and others.)

As organizations grow, they produce more information. More information helps, but it carries costs. Approaches to managing information, via Shannon and Kolmogorov.

The more structured a system is, the less information required to describe it. Conversely, more information is required to describe a disorganized or unstructured system. (p. 316)

❤️

On to part three of the book.

Chapter 8: What to Teach Our Children — The Future of the Organized Mind

Gist: in a world where understanding information is more consequential than ever, we need to teach (and learn!) information literacy. All opinions aren’t the same; some people are experts in particular domains while others aren’t. E.g., Levitin is skeptical of the value of Wikipedia vs. expertly-edited encyclopedias.

(My counterargument: “Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.” — Eric Raymond. Still, I agree that we must teach and learn how to better discern the sources of information — and the motivations behind them.)

This has to be what we teach our children: how to evaluate the hordes of information that are out there, to discern what is true and what is not, to identify biases and half-truths, and to know how to be critical, independent thinkers. … As soon as a child is old enough to understand sorting and organizing, it will enhance his cognitive skills and his capacity for learning if we teach him to organize his world. (p. 336)

We need more information literacy. Information isn’t the same as journalism, which contextualizes information. “Journalism is what you do with [information].” — C.J. Chivers (cited in p. 339) We perceive both through the lens of our biases.

We must be especially wary of the provenance, intent, and biases of information on the web, where anybody can publish. Three aspects of web literacy: authenticate, validate, and evaluate. Another key aspect: understanding that correlation doesn’t imply causation. (We see the effects of not understanding this in the news all the time.)

Yet another key aspect: boundary conditions. Consider numbers logically and critically. E.g., if someone says 400m people voted in the last U.S. federal election, your general knowledge of the world should tell you this can’t be right.

The last couple of sentences in the chapter summarize its gist:

… it is crucial that each of us takes responsibility for verifying the information we encounter, testing it and evaluating it. This is the skill we must teach the next generation of citizens of the world, the capability to think clearly, completely, critically, and creatively. (p. 369)

Chapter 9: Everything Else — The Power of the Junk Drawer

The gist: you don’t have to categorize (control?) everything; make room for miscellany and serendipity. Much of the external world has already been organized for us. E.g., the U.S. highway system’s road numbering scheme (which is more elaborate than you’d imagine): knowing how roads are numbered gives you a sense of their purpose and orientation, helping you locate yourself. Another example is the periodic table of the elements. Mendeleev’s model allowed chemists to predict the existence of elements that hadn’t yet been discovered or synthesized.

Organization schemas help us think better by externalizing our thinking. But sometimes we don’t have the advantage of doing so, as when we’re trying to memorize people’s names. We can use mental tricks in such cases to anchor our memories to known things and places.

Creating conditions for serendipity: “… in the pursuit of knowledge, slower can be better.” (Gleick, cited in p. 377) Slower and also smaller; when looking for connections, we’ll have greater success browsing a small library than the Library of Congress.

The twenty-first century’s information problem is one of selection. (p. 379)

Two strategies for selection: searching and filtering. (These distinctions sometimes blur in my mind. Perhaps filtering assumes a limited set, whereas searching is more open-ended?)

Junk drawers aren’t necessarily bad — but we must strive to purge unnecessary stuff/ideas/relationships.

We must consciously look at areas of our lives that need cleaning up, and then methodically and proactively do so. (p. 383)

Make space for better things.

This marks the end of the book’s main content. There is also an appendix that explains how to build simple Bayesian probability tables and extensive notes. I’m not reading through either the appendix or the notes at this time, so I won’t comment on them here.

Overall thoughts on the book

When I first read it (in 2018), I wrote that the book covers a lot of ground and as a result I found it to be something of an intellectual junk drawer. However, we shouldn’t be misled by the word “junk” in that phrase. As the book’s final chapter makes clear, jumbles of things (and ideas) can be powerful. “The Organized Mind” is an example. It offers practical advice on how to organize our lives with a grounding on neuroscience.

Some parts of the book focus on neurology, others in psychology, management, statistics, etc. The author offers clear examples throughout, which make difficult concepts clear. The bigger challenge is weaving them into a cohesive whole; I’m not sure it succeeds. But it’s worth reading.

Final takeaways for me:

- We understand reality by organizing it

- Categorizing is inherent in humans

- Some distinctions aren’t intuitive

- We must rely on others’ org schemes (expertise)

- We must develop information literacy (discerning expertise)

Those of us who design information systems need to be aware of how people understand and organize information. The Organized Mind offers many science-backed insights that can help us design better information systems.

Amazon links on this page are affiliate links. I get a small commission if you make a purchase after following these links.