Now that we all have computers in our pockets, digital note-taking has become commonplace. For example, you may be working when you remember you’re out of dog food. You take out your phone, open the notes app, start a new note, and write “buy dog food.” You do this for all sorts of other things: a book you want to read, an idea for a project, a list of holiday gifts, etc. Note-taking is an excellent way of augmenting our cognitive apparatus by delegating memory to an external system.

While we’ve long been able to do this with paper-based pocket notebooks, our phones are more flexible and convenient: they allow us not just to write down words but also to dictate them, take photographs, doodle with our fingers or a stylus, etc. Compared to paper notebooks, smartphones have an almost infinite capacity for capture.

Many people capture thoughts with their phone or computer and leave them be. Notes accumulate in their note app’s “inbox” in the order they were captured, producing a long list of unrelated notes. I’ve seen inboxes with many hundreds (or even thousands) of notes. Later, when the person needs some particular information, they browse the list or search for a term they remember writing down. This is easier to do with a digital system than with a paper-based notebook.

In either digital or paper notebooks, seeing recent notes is relatively easy. But older notes are challenging: you must not only flip or scroll back to find the note in the notebook or app but also cast your mind to the context in which you captured the thought. You might not remember the correct term to search for — or even the fact that you captured a note about this at all! You might also have had the experience of finding a note you took a long time ago and being unclear on what it means — it made sense when you wrote it, but now… not so much.

Which is to say, even with digital notes, there’s some cognitive friction with looking for older stuff — unless you do something about it. What can we do? We can organize our notes. There are two basic ways of doing it: top-down and bottom-up.

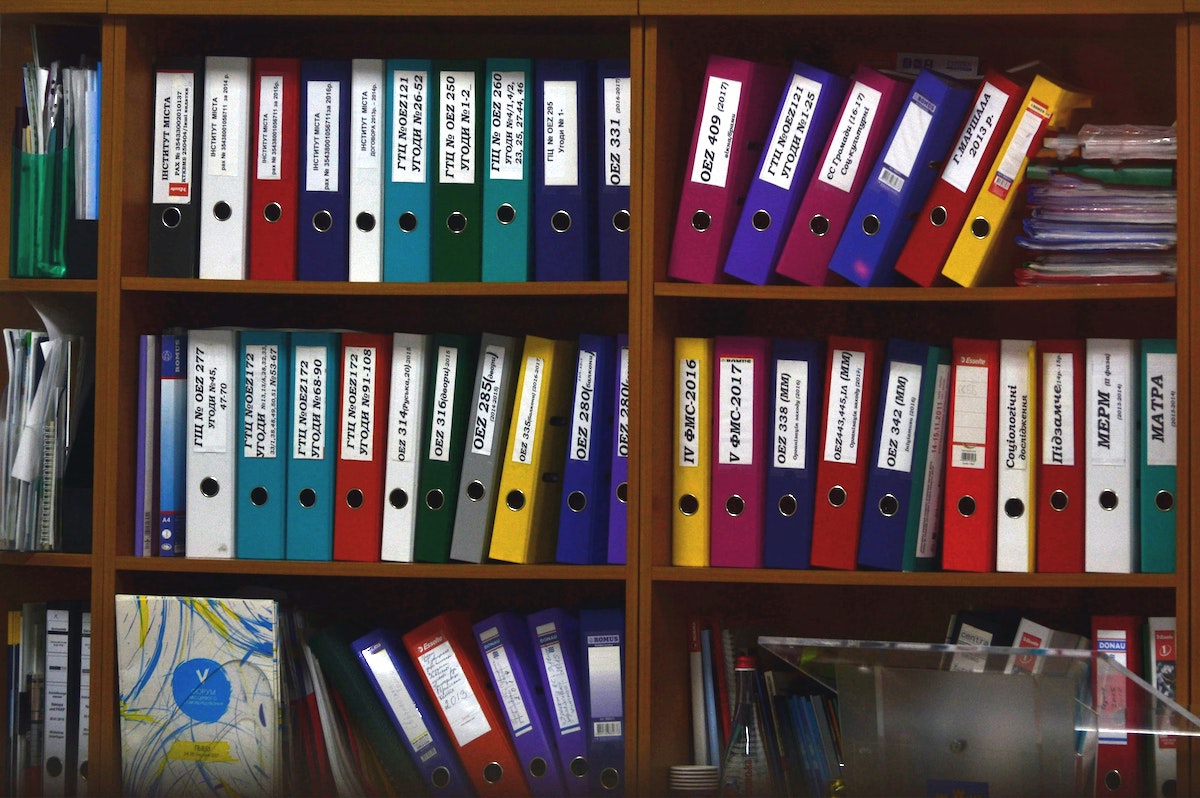

Top-down organization involves filing notes under one of several pre-determined categories. Before computers, most organization schemes worked by storing items in discrete containers such as folders, drawers, etc.

For example, when I was in school, I kept notes in a three-ring binder called a Trapper Keeper. It used loose-leaf paper for notes and cardboard dividers that grouped notes into sets, one per subject. (E.g., English, history, biology, math, etc.) I’d take notes on loose paper leaves and afterward insert them into that subject’s section in the binder. Keeping related notes (i.e., ones from the same subject) close to each other made them easier to find them later when it was time to study or do homework for the class.

Most digital note-taking apps also allow you to group notes into sets. These are digital analogs of subject dividers in a Trapper Keeper: they enable us to keep related notes together. For example, the default iPhone Notes app allows users to create or move notes into folders. Unlike paper binders, such apps can have an almost unlimited number of folders containing a nearly infinite number of notes. In the case of Apple’s Notes app, folders can also contain subfolders.

There’s another key difference: paper binders are constrained by the laws of physics: it’s reasonable to have five to seven sections but not hundreds. Digital note-taking systems have no such constraints; with these apps, it’s almost as easy to create a new set or category as it is to create a note. While convenient, this capability also poses a challenge: you may end up with too many categories, making it difficult to decide where notes should go and where to find them later.

When you can have fewer than (say) ten categories, you must be mindful about what they represent. This range works relatively well for schoolwork since most students study fewer than ten subjects at any given time. I remember creating the subject dividers at the beginning of the school year: I knew upfront that dividers would mirror my classes and that this taxonomy was unlikely to change during the school year. Hence, this was a top-down organization scheme, dictated from outside the system.

Bottom-up organization is the opposite, as you might expect. Instead of starting with a limited set of predefined categories, order emerges in the process of capturing and curating notes. This is more common in digital note-taking systems than in paper-based ones, and it often manifests as tags and other metadata associated with individual notes.

For example, you can type #shopping as part of the body of the note about dog food. In many note-taking apps (including Apple Notes,) words prepended with the hash character (such as #shopping) become tags. Such apps also allow users to browse notes by tags, so you can see all other notes that include the keyword #shopping. This makes it easy to organize notes on the fly since you don’t have to consider what category they belong to during capture. You simply type a particular word into the body of the note, and the system groups them for you.

As with top-down categories, you risk having too many tags. For example, you might have tagged one note #shopping and another #petshop. Both are meant to serve the same purpose but are different labels. Fortunately, many digital note apps that support tags also allow users to edit them. It’s good practice to occasionally review the list of tags in the system to remove redundancies, delete obsolete tags, etc. If you’ve consolidated all notes tagged #petshop and #shopping, you’ll be more confident that you’re looking at all possible notes related to that subject.

Again, such bottom-up organization schemes are more feasible with digital note-taking systems. But many apps support both bottom-up and top-down schemes. By combining both, we can find and use notes much more effectively. Maintaining such a system takes some extra work, but it’s worth it. Our minds are amazing pattern-matching systems, and we can augment them by articulating those patterns in digital note-taking systems. Doing so is a superpower — one that’s available in many pockets.