Master craftspeople don’t just work to make stuff; they also work on the work itself. A master carpenter will set up his shop for efficiency, develop deep relationships with his tools, and establish practices, habits, and mindsets that allow him to work in a state of flow.

Knowledge workers, too, must work on their work. As with craftspeople, this entails building empirical knowledge, developing generative mental models, and stewarding a toolset/environment that supports productive work.

For knowledge workers, the core of that toolset is software for archiving, creating, and managing information. These are applications that allow us to save things for easy recall, write notes, discover relationships between concepts, and more.

Digital note-taking isn’t new, but there are new apps that enable exciting new capabilities.

Among their core features, even the oldest operating systems let us save and manage text files. And personal information management (PIM) software has been around for decades. (I’ve used Tinderbox since the early 2000s.)

But there’s a raft of new applications, such as Notion, Roam Research, and Obsidian, which offer advanced capabilities in easy-to-use interfaces. On the surface, these apps might seem to be “note-taking” tools, but they’re much more than that.

Traditional note-taking apps, such as Apple Notes, allow you to capture ideas, bookmarks, shopping lists, etc., in a linear sequence, as you would in a paper-based notebook. That is, you write one note after another, and then view them sorted by creation date/time, often with the newest notes on top.

It’s a powerful way of getting stuff out of your head before it vanishes — an essential capability in our distracting, information-drenched world. But the chronological structure isn’t optimal: recalling what you wrote months or years ago will require some effort if you write lots of notes.

Admittedly, many traditional note-taking apps allow you to reorganize your notes. For example, you may be able to change the order of notes, rename them, put them into different “folders,” “notebooks,” or “sections,” etc.

These capabilities help. But taking time out to impose a top-down structure on your notes breaks flow. Also, the optimal order often isn’t apparent until you’ve already captured lots of notes, at which point reorganizing them becomes a pain.

The new note-taking apps are different. While they, too, allow you to create notes in a linear sequence, they also enable the emergence of bottom-up structures. Specifically, these apps make it easy to link one note to another and — importantly — expose that connection as a “back link” from the second note.

For the most part, these are traditional hyperlinks of the sort you see on the web. But links can also be arbitrary tags that connect related notes into emergent sets. It’s a powerful capability since it allows you to loosely organize information on the fly.

For example, imagine that you’re on the market for a new house. You see a listing that meets your criteria, so you bookmark it in your note-taking app and include the tag #newhouse as part of the note’s text.

As you find more listings, you capture them in the same way. You might also save the criteria themselves as a note (e.g., “what we’re looking for”) and update that note as you learn more about what you want and what’s available.

Eventually, you meet with a realtor and write down notes from the meeting. As you type, you include the #newhouse tag. You also create a note for the realtor, including her contact details, and link her name in the meeting notes to her contact note.

You keep doing this for everything related to the house purchase project. Eventually, you’ll have lots of notes that include the #newhouse tag. The application allows you to see all the project notes together and navigate between them. And if you open the realtor’s contact note, you see a list of notes you’ve taken from all your meetings.

Now imagine having this capability not just for one project but for all your projects. Suddenly, you start seeing connections that weren’t obvious before, and finding relevant ideas that would’ve disappeared among all the other notes in a traditional system.

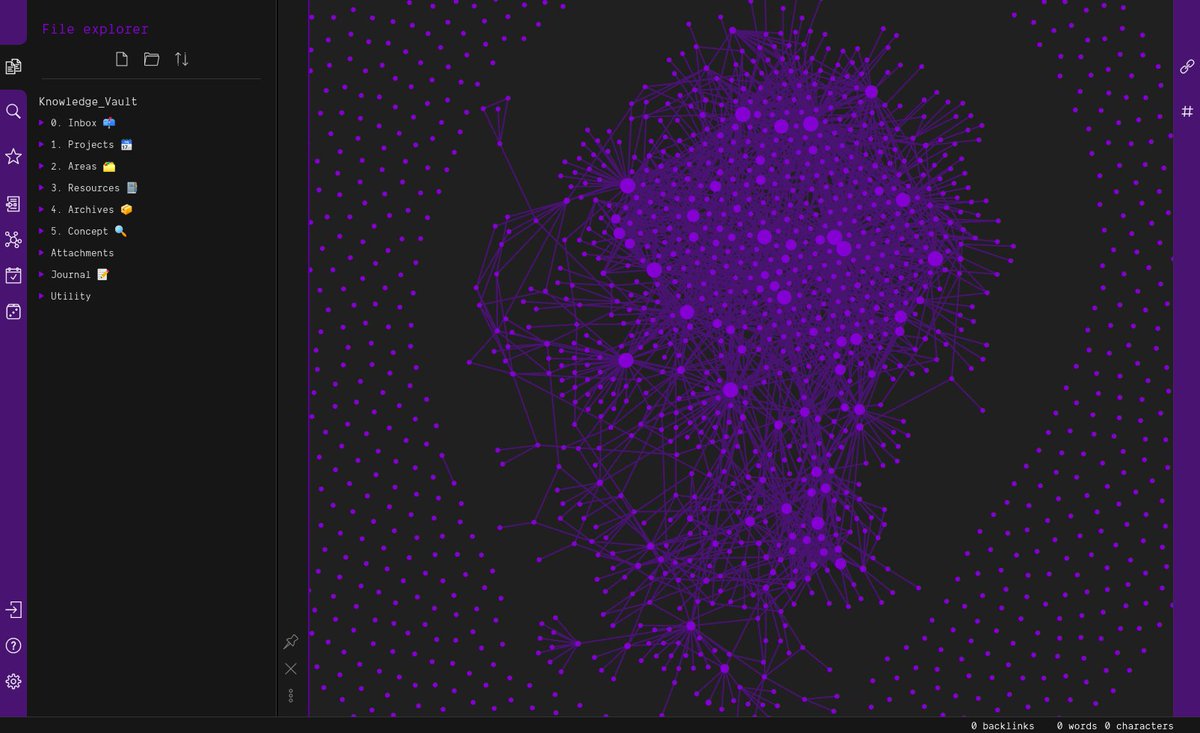

Some of these applications even let you see connections between ideas as a visual graph.

An Obsidian knowledge graph, via Twitter.

While this may sound like lots of extra work, in practice, it isn’t. You link and structure information in these applications incrementally, one note at a time. Structuring for recall and discovery is part of the note-taking process itself. You just need the presence of mind to type a few extra characters when you’re writing or editing notes. (Some apps, such as DEVONthink, also use AI to discover connections between notes.)

The biggest obstacle is overcoming the old mental model of notebooks as linear artifacts where you capture ideas in a sequential series of “pages.” Instead, it’s best to consider these systems as information gardens where you plant and cultivate ideas.

You’re not compiling books to sit on a metaphorical shelf. Instead, you’re building and stewarding a living system. As with vegetable gardens, hypertext PIM systems require ongoing work — but the fruits can be sweet, nourishing, and beautiful.

I’ve tested a couple of these applications over the past year, and have settled on Obsidian for reasons I’ll get into in a future post. For now, I’ll say that even though I knew what to expect in theory, I’m blown away by the practice.

I plan to share more about what I’m learning and how it’s changing my work, so please let me know if there’s anything specific you’d like to know. I’m also curious to know if you’re using any of these hypertext note-taking applications, and if so, how it’s going for you.