My family and I like board games. A few have become favorites that we play time and time again. However, we especially love learning new games. I’m often the one who reads through the rules to explain them to the rest of the family. When I do, I inevitably think of my work.

Much like an information environment, a board game is a little world. You inhabit that world when you play. You’re asked to make decisions between choices that are only relevant in that context. You do so towards achieving particular objectives and following particular constraints.

When you read the rules, you’re inducted into that world. You learn about the game’s theme and goals, and distinctions that only make sense in that context.

Consider the introduction to the most recent game we learned, called Planet:

A world is taking shape in the palm of your hands. Spread your mountain ranges and your deserts, expand your forests, oceans and glaciers. Strategically position your continents to form hospitable environments for animal life to develop and try to create the most populated Planet!

This statement evokes powerful imagery. It also hints at the major components of the game: You’ll manipulate continents to form environments, and the latter include mountains, deserts, forests, oceans, and glaciers.

What follows in the manual are refinements of these distinctions. You learn about the game’s components: what they are, how they’re different from each other, what they’re called, how they interact with each other, the states they can be in, the mechanics of transformation, and more.

Board games flex your ontology muscles.

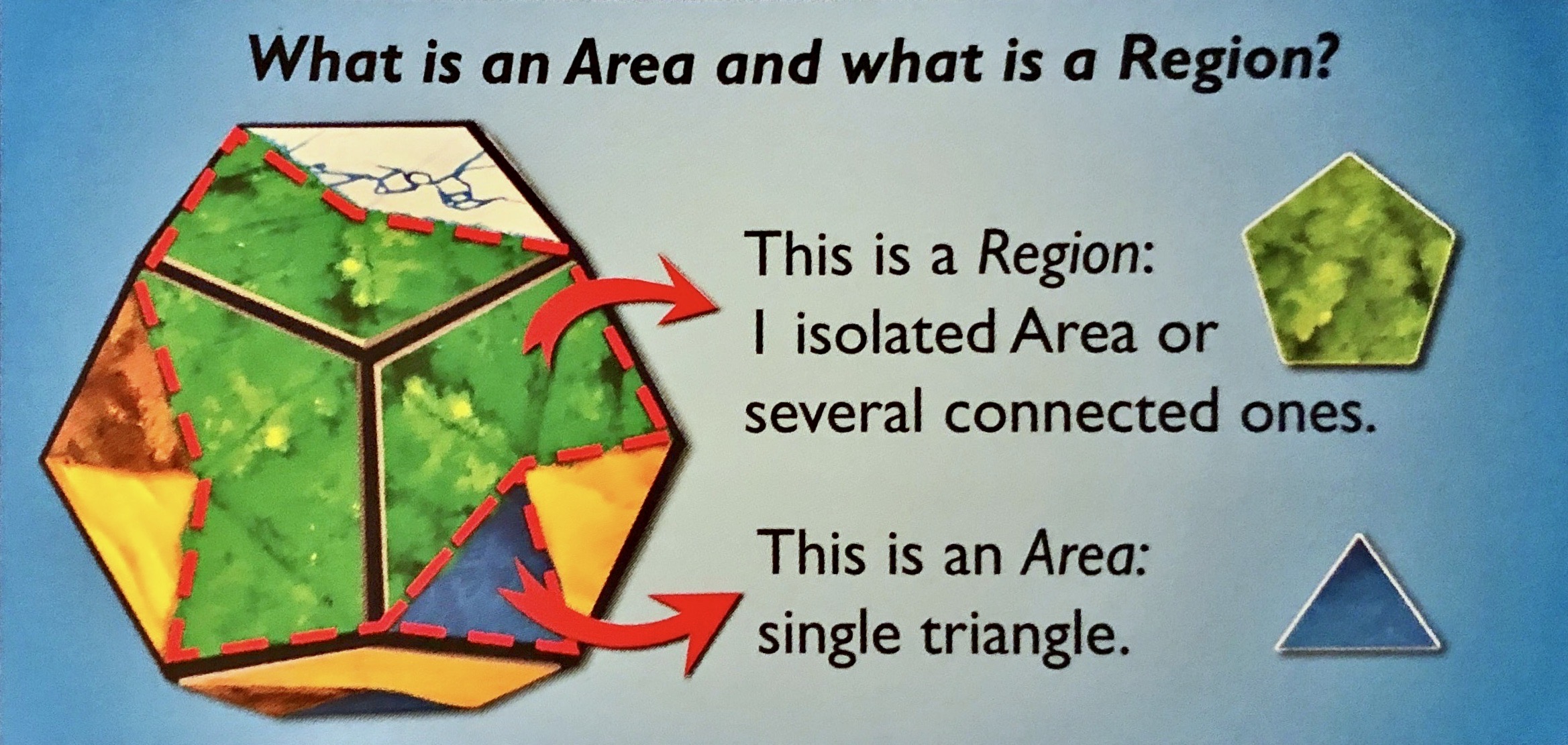

A detail from Planet’s instruction manual. © Blue Orange Editions

When designing an information environment, these muscles come into play. As with a game, you create distinctions that have special meaning in that context. (The distinctions make the context.) You label those distinctions in ways that (hopefully) make sense to users. You establish constraints to interactions between components in the system.

That’s the granular work. In a good system, those granular choices work together to evoke bigger ideas.

Technically, the game Planet would work if stripped of its ecological imagery and language. You could replace the beautiful renderings of animals and ecosystems with mathematical symbols that identify each piece, and the rules would still apply. But it wouldn’t be the same game. Your imagination won’t engage in the same way, you won’t learn as much, and the game won’t be as fun.

The theme and objectives are a crucial part of the game’s Big Picture. Here’s a sentence that spells it out for Planet:

Take on the role of super beings and compete to create perfect worlds with the ideal conditions for wildlife to flourish.

Such a clear Big Picture is especially important if you’re designing a complex system. With a Big Picture in place, many other design decisions fall into place. You get ideas for component names, images, colors, shapes, hierarchies, rules, and more. But the opposite isn’t true; you can’t produce a coherent Big Picture by starting from the details. (Although you can adjust the Big Picture as you gain a better understanding of the constraints imposed by your medium.)

We often move to work on details too soon. In digital design, especially, both designers and stakeholders push to work on screen-level artifacts prematurely. This drive is understandable since screens are “actionable.” But it’s a costly mistake. With no clear Big Picture in place to guide the process, decisions fall back on individual preferences, expediency, and — worse of all — politics.

If you’re designing a component of a complex system, ask yourself: What little world are we aiming to create? What goals will it serve? Who will inhabit it? Who will be its steward(s)? Are you clear on the Big Picture? If you’re not, perhaps it hasn’t been articulated yet. Why not? And, more importantly, how might you change that?

A version of this post first appeared in my newsletter. Subscribe to receive posts like this in your inbox every other Sunday.