I saw a news item a few weeks ago about an old Atari 2600 game called Extra Terrestrials, which just went on the market for $90,000.

Ninety thousand dollars.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Surely you mean E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, that godawful game that heralded the end of the Atari boom and which the company had to literally bury in a landfill. How can one cartridge of that turd be worth that much money?” (Well, that’s what you’re thinking if you’re a video game nerd.)

Well, that’s not the E.T. this story refers to. Towards the tail end of the Atari craze in the early 1980s, a family decided to self-produce a (derivative and by all appearances crappy) game called Extra Terrestrials. The market for video games tanked, but the family pushed through regardless, selling around 100 copies door-to-door. In other words, the game’s a rarity. (Here’s the full story.)

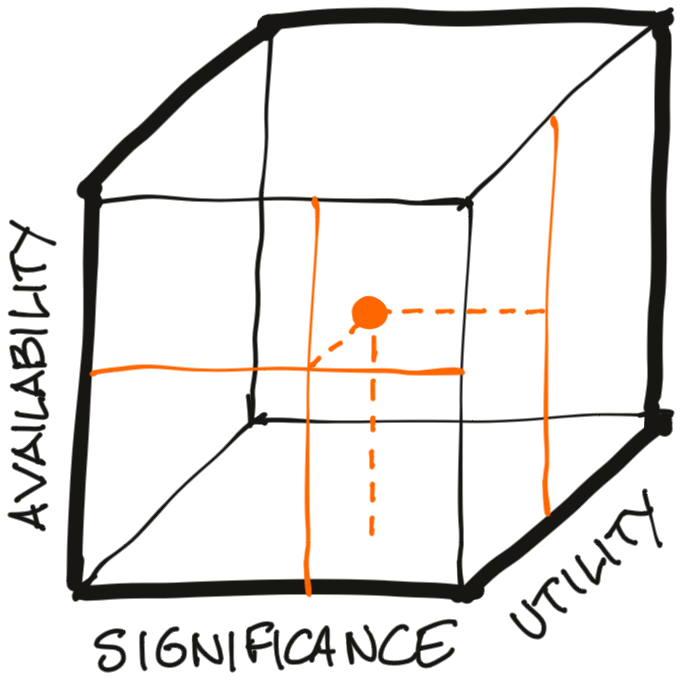

Is something like Extra Terrestrials worth $90,000? Well, it’s worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it. The broader question is, how do we determine the value of things? That is, how do we arrive at the price people will be willing to pay? Economists have models for this. (Feel free to point me to some you know.) My intuitive model looks like this:

There are three dimensions here:

Availability

How easy is it to avail yourself of the thing you’re buying? Something you can easily get at the nearest Walmart will be worth less than something like Extra Terrestrials, of which a limited number of copies are known to exist. (And which were produced over three and a half decades ago, making it likely that only a small subset survive.) On the extreme end of this dimension, you have things like Bach’s St Mark Passion, which has been lost. We know it exists, but nobody has a copy. What would one be worth?

Part of Extra Terrestrials’ high price is due to the fact that few copies exist. If you’re an Atari cartridge collector who’s obsessed with owning the catalog of all games that have existed (a “completionist”), you’ll be willing to part with a lot of money for something this rare. (I expect not many buyers fit that description.)

Significance

Another dimension is the social or cultural significance of the product. Some things have had an oversize impact on the course of history, and this makes them sought after. For example, while Apple I computers are relatively rare, they weren’t unique per se; lots of people were hacking about with incipient “personal computers” in the mid-1970s. However, the Apple I was the first product of what would become (arguably) the most influential computer company in the planet. This, combined with their relative rarity, makes Apple I units worth a lot of money.

Extra Terrestrials doesn’t score well in this dimension. I hadn’t even heard of it before yesterday, and I know more than most people about the history of video games. I’d say its influence in the history of video games has been nil.

Utility

This is the practical dimension: How much utility does the thing have? Neither Apple Is or Extra Terrestrials cartridges fare well here. If you own an Apple I, you’re unlikely to be using it for your day-to-day computing needs; it’s most likely stored (or displayed) under carefully controlled conditions. At this point an Extra Terrestrials cartridge is useful only as a museum piece, not to serve the functions for which it was originally designed.

Note the location of a product in the value model shifts over time. Something can start being abundant (and relatively unimportant) like the E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial cartridge. As time passed, fewer units are available so it’s become relatively scarce. (You can’t find one at your local mall.) Also, its significance has increased over time as it’s become a signpost for the implosion of the video game industry in the mid-1980s. Finally, its utility has decreased over time, as less people have Atari consoles in their homes.

In short, the value of the item — and the size of its addressable market — changes over time. Value is always fluctuating, always relative. Something may be worth very little to you now but be worth a lot to a collector four decades from now. A “list price” is useful for commodity items, but some items aren’t commodities. You’d be a fool to charge the original list price for a copy of Extra Terrestrials (or even E.T.) today; it’s too rare and — at least for some people — significant.

I’ve been talking about products. But what about services, such as design consulting? Services aren’t commodities — especially if the service you’re providing is highly differentiated and valued. As a consultant, you should be able to command a premium if a) you’re one of the few people who b) provides a service that generates (real and/or perceived) utility c) for organizations that understand its significance (and/or urgency.)

These are important caveats. The last point – helping clients understand the impact of design on their business — is particularly tricky. Too many folks (both on the client and provider side) still consider design interventions as cosmetic, and even those who think of design as more than that still frame it primarily as a problem-solving discipline — that is, as tactical.

Thus, the industry standard (at least in the U.S.) is for design services to be priced on a time + materials basis. When negotiating a contract, clients want to know a “standard hourly rate.” This strikes me as the result of a failure on our (design consultants’) part to clearly articulate the value of design. The onus is on the supply side to clearly communicate the value of what it has to offer.

Time + materials is the path of least resistance. A standard hourly rate is much easier to calculate than something like value-based pricing. But it’s a broken system. A rare game cartridge probably may not be worth $90,000 to you, but it could be worth that (or more) to somebody else. Market mechanisms will drive the price up or down; it’d be foolish to suggest it be treated as a commodity, to be offered to all takers at all times at a single list price — especially when there’s only one sample in the world.