One of the most important lessons I learned in architecture school was the power of constraints. I’d always assumed that in creative work, complete freedom leads to better, more interesting results. After all, given more latitude you’re likely to try more things. But this turns out to be wrong.

The problem is twofold. For one, there’s the paralysis that sets in when facing a completely blank canvas. What to do? Where to start? Etc. For another, you never really have total freedom in the first place. All creative endeavors must grapple with constraints. There are time limits, budgets, the physical properties of paper, the force of gravity, the limits of your knowledge, the limits of what your society deems acceptable, and more. All of them narrow the scope of what you can do at any given time. Understanding the constraints that influence the project — and learning how to work creatively with them, rather than against them — is an essential part of learning to be a good designer.

But it goes further than this. Sometimes doing good work calls for us to introduce constraints of our own. Think of the difference between great jazz playing and mere noodling around. The interesting improvisations happen against the constraints of rhythm and chord (or mode) changes. The musicians don’t have to respect these framing devices, but doing so makes the work come alive. The band’s rhythm section provides enough structure for the soloists to fly “free” — but always in dialog with the underlying structure, either pro or con.

I often think of the success of Facebook in this light. In some ways, Facebook is the apotheosis of the promise of the original World Wide Web. I remember thinking in the mid-1990s that one day everybody would have a web page of their own. However, the hurdles for doing so were too high at the time: you needed space on a web server to host your site, to learn HTML and web design, to understand all of these concepts. More importantly, you needed to have something to tell the world — a compelling reason to get you to overcome the inertia of not doing anything at all.

Over a third of humanity now has a presence online thanks to Facebook. No doubt this is because Facebook abstracted out the hosting and sharing bits. There’s no further need for you to learn HTML or design, or to find a web host! But of course, many other companies had been doing this before Facebook. What Facebook added to the mix was structure: you’re not just sharing arbitrary free-form stuff, you’re sharing the minutiae of everyday life: photos and short text updates. (Think of how limited text editing and presentation is on Facebook. You can’t even bold or italicize text!) And you’re not just sharing them with anybody who cares to read them; you’re sharing them with the one audience that may care: your friends and family.

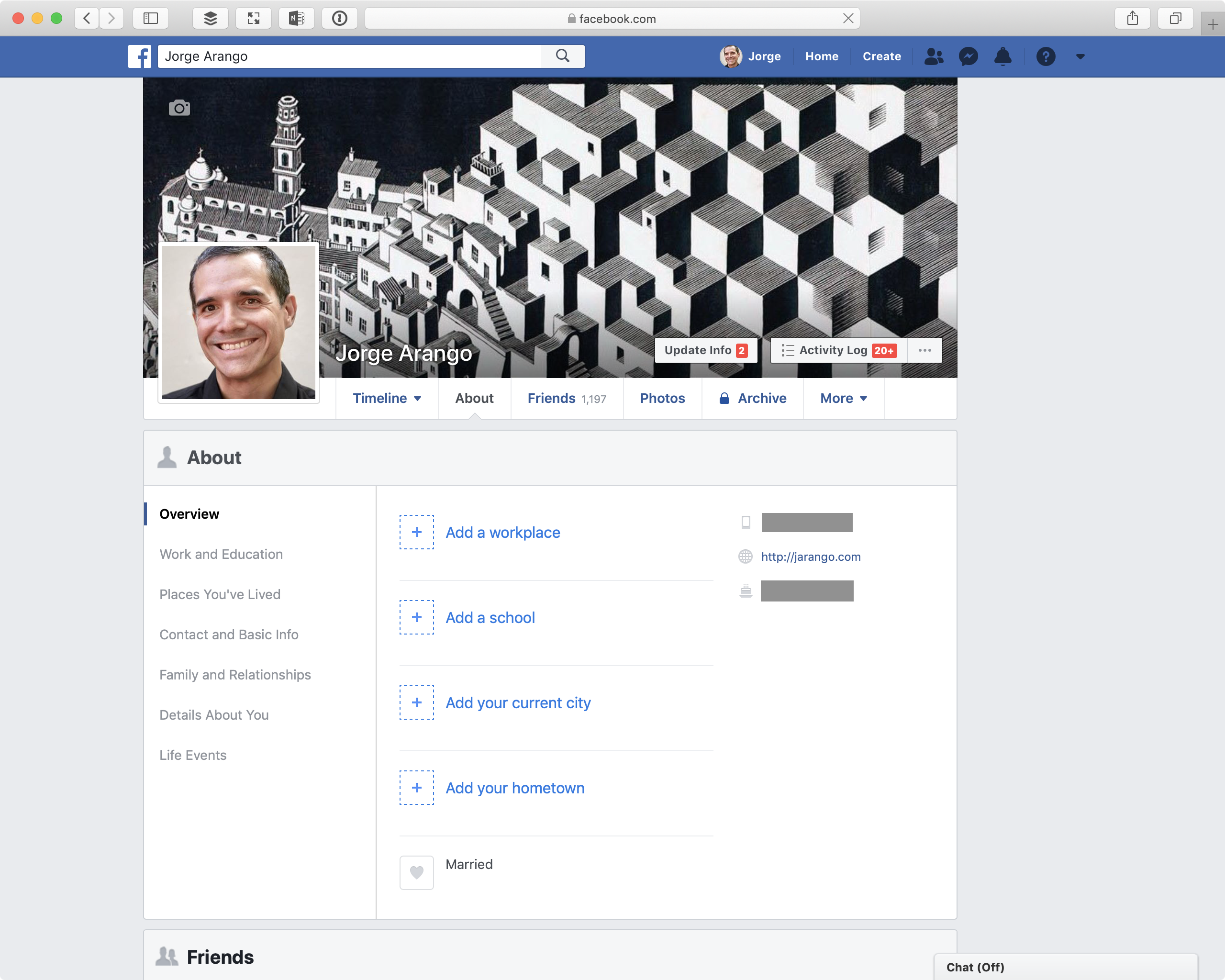

This structure underlies the entire system. It provides rails to the experience that make onboarding and day-to-day usage easier. The structure you fill out when you join is the same one you expect to see on my profile; you don’t need to re-learn it when you visit my profile page. Instead, you focus on the differences: the content I’ve posted. Text, photos, metadata about who I am — at least the ones I choose to share using the system’s structural constraints. I can tell you about where I live, or where I went to school, for example.

Tell me more…

We come to expect these structural constructs in the environment, in much the same way jazz players expect rhythm. At scale, these structural constraints become normative. We play with them and around them but never break or transcend them. For a system such as Facebook (which is financed by advertising), the configuration of these structures is the result of a delicate balance between the things people would be enticed to do with such a system (e.g., share their lives with their friends) and how advertisers want to categorize us. Studying these structures reveal a complex picture of who we are not just as individuals, but as participants in a market economy.

Leaning towards overly-prescribed structure, Facebook has successfully gotten lots of people online — using the infrastructure of the Web, but not its open-ended ethos. Given the importance of structure to bootstrapping creative endeavors, I wonder if it could’ve been otherwise.