I’m excited that we’re almost at the end of the year. I started this journey to explore our culture’s foundations. By now, we’ve left the lower levels and have moved into oft-visited antechambers. On week 48, Gioia recommended three familiar works: Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, chapter one of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, and Jorge Luis Borges’s Ficciones.

I’d already read all, so I skipped Kafka and García Márquez this week. But Borges is my favorite author and Ficciones my favorite of his collections. I’ve read several of these stories many times and The Library of Babel is part of the syllabus in my Systems Studio course. So this week, I revisited a few of the less-familiar stories in the collection.

Readings

Before diving into Ficciones, I’ll say a bit about the other two works. The Metamorphosis (1915) tells of Gregor Samsa, a salesman who awakens one day to discover he’s mysteriously turned into a large insect. His family tries to adapt to his new form, but it causes no end of trouble — not least because he can no longer provide them sustenance. A metaphor for life under industrialization.

One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), the best-known Latin American novel, tells the multi-generational saga of the Buendía family of Macondo, a small Colombian town that follows its own physical laws: anything can happen in Macondo. As I recall, the novel opens with the arrival of a miraculous new experience to town: ice. This sets the tone for the rest of the work. With the right framing, the banal turns magical.

On to one of my favorite works in literature, Jorge Luis Borges’s Ficciones. Initially published elsewhere, the first eight short stories were collected in 1941 as El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths.) Three years later, Borges appended six additional stories in a new section called Artificios (Artifices.) These two collections make up Ficciones.

Most of these aren’t traditional stories. Instead, they’re sketches that explore specific concepts. Several are meta-narratives in that their central concern is the nature of language itself. These are my favorites (along with very brief descriptions that don’t do them justice):

- Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius: a man discovers a new world in an encyclopedia, the product of a mysterious conspiracy.

- Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote: the titular character sets out to reconstruct verbatim one of the chapters from Cervantes’s novel — not from memory, but from lived experience.

- The Circular Ruins: a man dreams another man into existence, only to realize that he, too, is someone’s dream.

- The Lottery in Babylon: sketch of a society where decisions are left to chance.

- The Library of Babel: sketch of an infinite library as an exploration of semiotics.

- The Garden of Forking Paths: a proto-hypertextual spy story that foreshadows quantum mechanics.

- Funes the Memorious: after an accident, the titular character is cursed with perfect memory.

- The Secret Miracle: God grants a condemned man one last wish — which only he can experience.

- The South: a man journeys to Argentina’s rugged south to recover from a near-death experience only to learn of life’s arbitrariness.

Like I said, these descriptions aren’t fair. Borges’s ultimate subject is language: his best “stories” are labyrinths — mirrors — dreams that reveal the mystery and trickery of the very stuff they’re made from. Rather than lead us into and through the labyrinth, Borges shows us we’ve been there all along — at least since we started languaging.

Audiovisual

Music: Gioia recommended Tango, Cumbia, Bossa Nova, Afro-Cuban Music, and Reggae. Again, all familiar to someone who grew up in my part of the world, so I skipped them. That said, I did revisit songs by Jimmy Cliff, who died on November 24.

Arts: Antoni Gaudí, whose major works I’ve had the privilege of visiting. Like Kafka, Borges, and García Márquez, these works set up their own rules and play out the consequences. Gaudí’s worlds we can literally inhabit (rather than inhabit literally.)

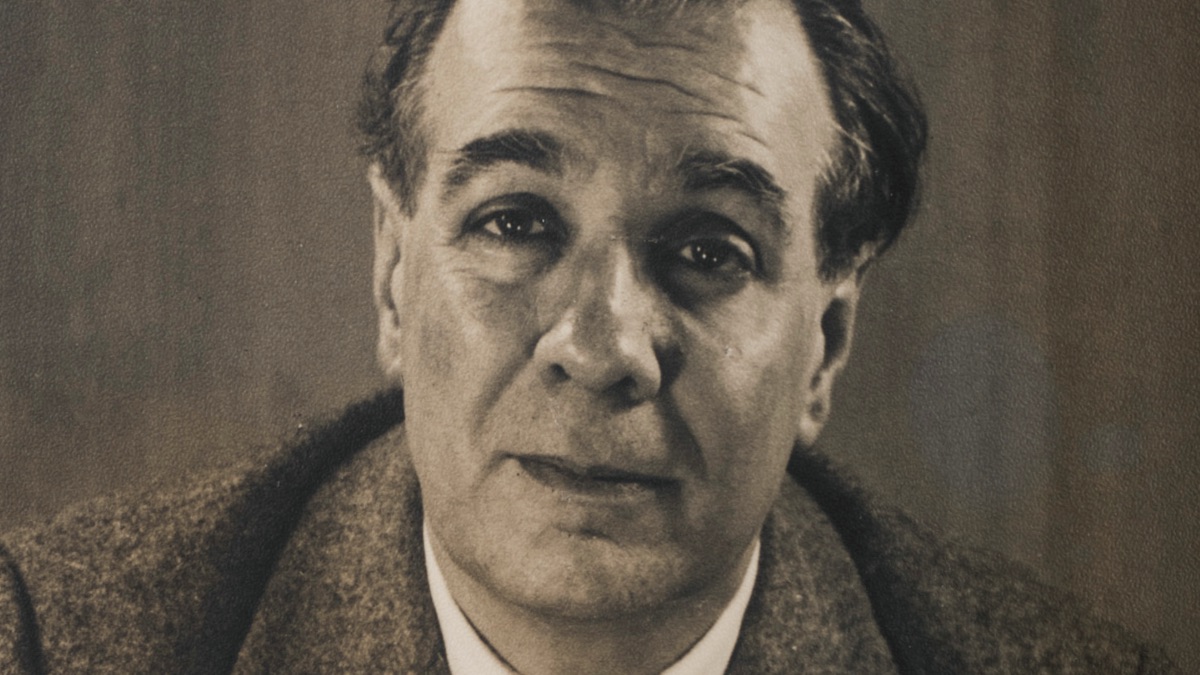

It’s about time I shared a selfie in the course.

Cinema: Francis Ford Coppola’s THE GODFATHER (1972) — one of the best works of American cinema.

I’d seen it before, but jumped at the chance when my boy showed interest. Like One Hundred Years, it’s a multi-generational saga that revels on imagery verging on surrealim. (E.g., Jack Woltz discovering the nature of Don Corleone’s “unrefusable” offer.)

Reflection

García Márquez is a huge figure in Latin American culture: the most translated Spanish-language author, 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature, etc. He also influenced other important writers. An avid socialist, he keenly observed and parodied the idiosyncrasies of Latin American society. You’ll think I exaggerate when I say I’ve visited Macondo and know the Buendías.

For a while in the 1980s, Gabo’s work was de-rigeur. By 2025, it feels passeé. Yes, life in the tropics is still rife with absurdities, non sequiturs, beauty, and banal monstrosities and miracles. But ice doesn’t seem as miraculous now that everyone in Macondo has access to Google, YouTube, Spotify, and ChatGPT.

Borges, on the other hand, remains deeply relevant. The Library of Babel and The Garden of Forking Paths aren’t so much mind-bending stories as foundations for an Information Age mythology. Although technically an Argentine, Borges was an erudite polyglot whose true homeland was the Library (which others call the universe.) His work should be better known.

Notes on Note-taking

This week, I reverted to even older-school practices: Wikipedia and notes written with a fountain pen. There’s a tangible difference between typing out words on a screen and moving a nice nib over paper. That I can’t summon ChatGPT in my Leuchtturm notebook is a feature, not a bug. These words might include more factual errors, but they’re closer to my soul.

I also find myself writing more in Emacs. I started this post in Ulysses on the iPad, but for some reason the app became infuriatingly laggy as the post grew longer. I like the idea of writing on the iPad, since it’s a more portable setup than my 16” MacBook Pro. But I have so much muscle memory on top of Emacs — and it’s more reliable.

Hand-written notes and a ~50-year-old text editor. Back to the past as we near the end of this year-long experiment.

Up Next

Gioia recommends selections from Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault, and René Girard — deep influences on current culture. As I suggested above, my main interest in the course was exploring the foundations; I’m indifferent to more contemporary stuff. (Except Girard — I’m keen to read him.)

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!