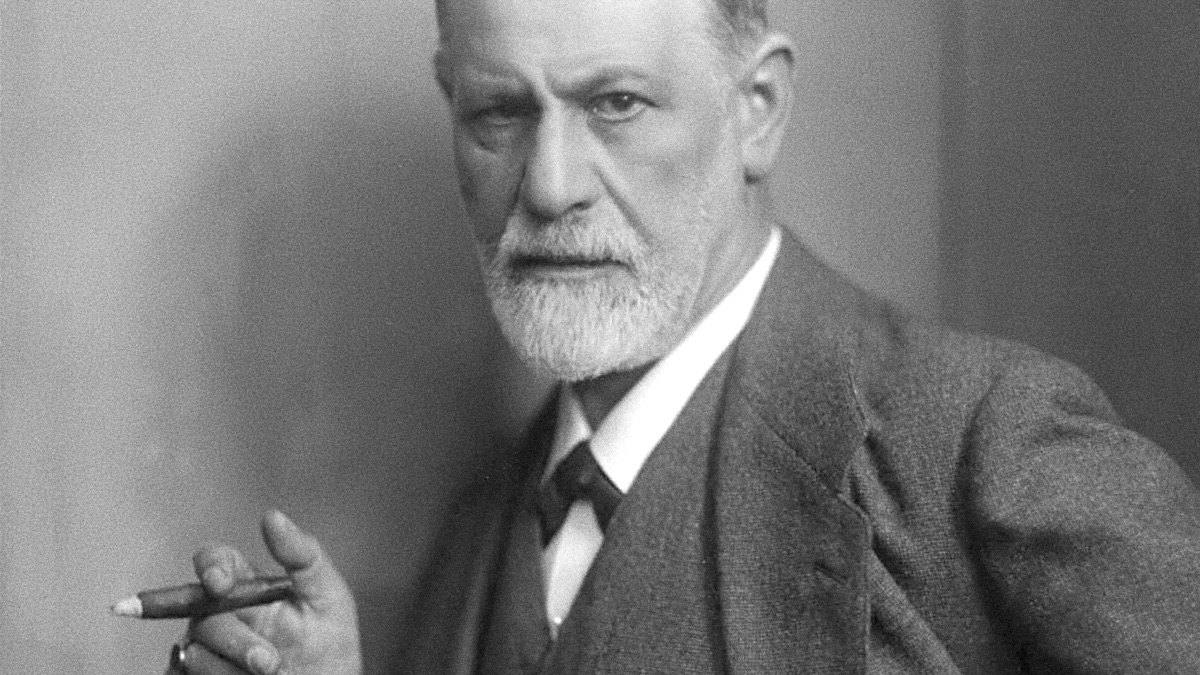

In week 46 of the humanities crash course, I read works by one of the most influential thinkers of the Twentieth Century: Sigmund Freud. Gioia recommended two essays: An Outline of Psychoanalysis (1940) and Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). I also watched a classic sci-fi/horror/action movie that seemingly had nothing to do with Freud — but ChatGPT might convince me otherwise.

Readings

I’ve been able to download most of the reading materials for this course for free. But now, I’m in the part of the course where readings aren’t in the public domain. Both of this week’s readings are available in a single volume called The Penguin Freud Reader, so that’s what I got.

Let’s start with An Outline of Psychoanalysis, an essay whose purpose is

to offer as it were a dogmatic conspectus of psychoanalysis by bringing together all its doctrines in the most concentrated and clear-cut form.

That is, it’s an overview of Freud’s thinking. His focus is the psyche, which can be approached from two perspectives:

- The mind’s physical setting, i.e., the nervous system

- Minding itself (my language), i.e., acts of consciousness

Freud isn’t concerned with the former. He hypothesizes the latter as composed of three “psychical provinces or forces”:

- The Es or Id, which is driven by unconscious instinctual drives — i.e., inherent to our nature as embodied beings.

- The Ich or Ego, which balances the Es, the Über-Ich, and external reality so we can function in the world.

- The Über-Ich or SuperEgo, which are internalized societal limitations internalized from interactions with our parents and cultures.

Both the Es and Über-Ich represent drives from the past. The Ich, on the other hand, mediates opportunistic responses to the present. Neuroses and pathologies can be attributed to conflicts between the forces, repression of painful memories, and inadequate defense mechanisms. A healthy balance is required.

How do we do it? By observing our minds. But we can’t do it alone. Some memories, for example, might be unpleasant, so the Ich represses them. One way to get our psychic house in order is to talk about our experiences with a trained therapist. Freud emphasizes specific techniques, such as free association and the interpretation of dreams.

There’s more to it, but these are the main ideas I got from the Outline. I was confused at first by the terms Es, Ich, and Über-Ich. I’d heard of Id, Ego, and Superego, but these terms weren’t used in this translation. ChatGPT helped me understand they referred to the same ideas.

On to the second essay, Beyond the Pleasure Principle. I found it more technical and therefore less accessible. The gist is that two fundamental drives motivate human action:

- The Pleasure Principle, our drive towards pleasure and away from pain. As GPT put it, the PP focuses “on survival, reproduction, and other life-sustaining abilities.” This explains our tendency to seek immediate gratification of needs and desires.

- The Death Drive we have towards aggression and destruction. It’s in tension with the Pleasure Principle, and can manifest in self-destructive behaviors and actions that can harm others.

The key is that we don’t just seek pleasure: we also have destructive tendencies. The interplay between these drives explains otherwise baffling behaviors. But frankly, I only got this after working on my reading notes with GPT-4o. As I said, I found this essay rather technical and dry.

Audiovisual

Music: Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, and Barber’s Adagio for Strings. The former was new to me. I’d heard two movements of the Messianen work in a collection of Twentieth Century classics called The Calm. The Barber is ubiquitous. This is music you grow into.

Arts: The surrealists: Dalí, Magritte, Carrington, Miró, Ernst, Sage, Tanguy, Varo Uranga, de Chirico, Tanning. I was very interested in surrealism as a student and was aware of most of these artists’ works.

](/assets/images/2025/11/de_chirico-song_of_love.jpg)

The Song of Love (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico, Museum of Modern Art via Wikimedia

Although Dali is the most famous, I’ve always thought him overrated. De Chirico has long been my favorite: he influenced my own college paintings. But in general, I’ve lost interest in surrealism. In retrospect, the movement’s goals strike me as folly.

Cinema: John McTiernan’s classic 1987 sci-fi/horror/action film PREDATOR, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger.

This may seem like an odd choice. It’s decidedly low brow compared with other films I’ve seen in the course. (Except my other sci-fi pick in the first week.) But at this point, I wanted something less intellectually demanding. Also, my son had been wanting to see PREDATOR and this was a good opportunity to bond around some cinematic testosterone.

This is the kind of film where men with huge biceps fire off endless rounds of ammunition into baddies (and in this case, the jungle) while casually dropping “clever”/cruel one liners. The sci-fi angle comes from the titular character, an extraterrestrial trophy hunter.

For the record: this film is better than I remembered. The pre-CGI SFX by R/Greenberg Associates are clever and effective and Alan Silvestri’s martial score keeps the (audience’s) blood pumping. Bonus: I found a way to fold the film into the course’s didactic goals. More below.

Reflections

Here’s where I’m gonna piss off some folks. I realize Freud has been hugely influential. The concepts of the Id and Ego have permeated Western culture. We speak casually of repressing memories and of interpreting dreams as a way to bring them to consciousness. Many people are in therapy and assume it to be normal and healthy. All that said, I’ll be plain: I didn’t like these essays.

The main problem is with how they jump to huge, momentous conclusions from what seems extremely thin evidence. Surely I missed a lot by only reading an overview, but I didn’t get how Freud came to his elaborate theories. As far as I could tell, his ideas are based on conjectures and hunches derived from a few clinical cases and firsthand experience.

And some of his theories are doozies:

The child’s first erotic object is the maternal breast that feeds it; love arises on the pattern of the gratified need for nourishment… And, regardless of how long the child was nourished by its mother’s breast, it will always remain convinced once it has been weaned that it was not long enough, and that she did not give it enough food.

This is followed by astonishing claims about the child’s sexual desires towards his mother, the effects of her implied threat of castration, and how girls deal with such feelings:

The female child doesn’t, of course, have to fear losing her penis; however, she does have to react to not having had one in the first place. Right from the start, she envies the boy his possession; indeed, one could say that her whole development takes place under the influence of penis envy.

Say what now?

As Carl Sagan would put it, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. And I didn’t get how Freud could justify such claims. To me, he seemed more prophet than scientist. Perhaps his popularity is due to his therapies filling the religion-shaped hole left by Nietzsche?

“Talk therapy” is a service spiritual counselors provided for most of human history. While the language is different, the ideas aren’t radically new: priests would’ve spoken of demonic possession rather than the Id and Buddhists were transcending the Ego centuries before the term became fashionable.

People need this kind of support. It’s not surprising that science would provide answers after religion’s retreat. But how is this science?

Notes on Note-taking

As I’ve done with previous challenging readings, I asked ChatGPT 5 for help with both essays. Its responses were helpful, as I mentioned above. When I was done, I decided to have some fun, so I entered this prompt into the same chat:

Thanks for your help with these essays. Let’s examine the ideas in these essays through the lens of a popular work: the 1987 sci-fi/action classic film PREDATOR. Adopt the personality of a Freudian analyst looking to find patterns in this movie. Are you familiar with the film’s plot? How would you interpret it in light of Freud’s ideas?

Its responses were hilarious — and in some cases, helpful. First, it acknowledged knowing the work in question:

Oh yes—I know Predator. Put me in my Viennese armchair and let’s read this jungle dream.

The fun started with a map of what ChatGPT called a “cast of the psyche”:

- The Jungle = the Unconscious. Dense, teeming, opaque; things move there before you can name them.

- Dutch (Schwarzenegger) = the Ego (Ich). Practical, reality-testing, forced to adapt. He survives by planning and binding raw fear into workable tactics.

- The Team = Ego’s defenses. Bravado, jokes, rituals—denial, reaction formation, displacement (that glorious minigun tantrum into empty trees).

- The Predator = the Death Drive / cruel Superego. A judging hunter with a “code,” meting out exquisite punishments, and finally willing to blow everything to zero. (In Freud’s terms: Todestrieb shading into a sadistic Superego.)

- Guns, knives, muscles = phallic emblems. The film delights in them… then shows how easily they’re stripped away.

This last point made me chuckle. ChatGPT then proceeded to analyze the movie through different lenses:

- Key scenes seen through psychoanalysis

- Fit with the Pleasure Principle

- Id-Ego-Superego lens

- What the movie “works through”

I won’t quote the whole thing, but here are some highlights. (Spoilers!)

- The macho handshake & banter. Classic reaction formation: overdone toughness to ward off anxiety. The Ego armors itself in muscle and jokes.

…

- “There’s something out there.” The Uncanny (das Unheimliche): familiar shapes flicker, but can’t be fixed by sight or name. Invisibility = the repressed acting without representation.

…

- Mud-camouflage & Stone-Age traps. Dutch cools his “heat” to near zero to evade the Predator’s thermal gaze. That’s Freud’s Nirvana principle made literal: tension pushed toward zero. And the reversion to primitive tools is regression in the service of the Ego—going backward to go forward, to master the trauma.

…

- Self-destruct with maniacal laughter. The death drive unveiled: not just killing the other, but annihilating the field itself—“back to the inorganic.” Also the cruel Superego getting the last word: if I can’t have the trophy, no one will.

…

Id–Ego–Superego quick lens

- Es (Id): Raw aggression and thrill—the film’s fetish for weaponry and spectacle.

- Ich (Ego): Dutch’s reality principle: observe heat-vision, test mud, set snares.

- Über-Ich (Superego): The Predator as judge enforcing a perverse chivalric law; also the team’s internalized “be a man” mandate that makes retreat unthinkable until it’s too late. Superegos can be merciless—Freud emphasizes this—and the Predator’s punishments feel exactly that.

What the movie “works through”

- From invulnerability to castration anxiety. The film lovingly builds phallic invincibility (biceps, blades, bullets) only to humble it. Survival requires relinquishing the fetish objects and relying on wit and the environment.

- From the Uncanny to the Mortal. Once the unseen becomes seen, the terror becomes killable. That’s textbook analytic progress: make the repressed appear, then bind and integrate it.

Some of this verges on parody, but some is insightful. And it highlights LLMs’ ability to find patterns in data. Doing an on-the-fly analysis of a work through a particular lens is genuinely useful.

The challenge, of course, is that I don’t know enough about Freud to know if any of this is fair. ChatGPT seems to acknowledge as much in its closing statement:

Does this reading prove anything “true” about the movie? No—Freud is a lens, not gospel. But through that lens, Predator becomes a tight parable about how the Ego survives: not by louder guns, but by turning the unseen into the known, surrendering false potency, and mastering the drive toward annihilation long enough to get to the chopper.

Useful? Perhaps. Entertaining? Definitely.

Up Next

Gioia recommends seven short works: the prologue and first chapter of Ellison’s Invisible Man, one section of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, Fitzgerald’s The Diamond as Big as the Ritz, Hemingway’s The Killers, Jackson’s The Lottery, O’Connor’s A Good Man Is Hard to Find, and O’Henry’s The Gift of the Magi. I assume I’ll have to buy all/most of these — if I can source them at all.

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!