Week 45 of the humanities crash course had me delving on the mysteries of time as experienced by us puny humans. (Wow, that sounds both grandiose and dismissive!) In particular, I read two poems by T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf’s modernist novel To the Lighthouse. I also watched a classic and challenging film centered on boxing.

Readings

The two Eliot poems were The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock and The Waste Land. I’ve already stated several times during the course that I’m not a fan of verse. While I love songs, I find most poems difficult to grok. These were no exception, so I relied on secondary readings for their interpretation.

GPT 4o tells me The Love Song “explores themes of indecision, insecurity, and the passage of time.” I have to take its word for it: I didn’t get the poem. The Waste Land also baffled me. Its abrupt shifts felt intentionally difficult and pretentious. This is part of the point, since it reflects the fragmentation and disillusionment following World War I. As GPT put it, “Through a collage of voices, languages, and literary references, Eliot depicts a world that is spiritually barren and culturally decayed.” The bleakness came across even to someone as tone-deaf as me.

To the Lighthouse is also fragmentary, but has a much warmer and empathic tone. The novel explores the inner life of the Ramseys, an English family in the first decades of the Twentieth Century, through their relationship to their vacation home in one of the Hebrides islands. It’s told in three parts.

In the first part, Mr. and Mrs. Ramsey and their eight children are in their vacation home discussing the feasibility of visiting a nearby Lighthouse to deliver a parcel of supplies to its keeper and his son. Their 6-year-old son, James, is especially keen on the adventure. They’re also joined by Lily Briscoe, an artist who is trying to paint on their estate.

Mrs. Ramsey is described as a beautiful, smart, optimistic, and singularly deep woman who holds her family together. Her husband is the opposite: ornery and overbearing. Mr. Ramsey is doubtful they’ll make it to the Lighthouse, since the weather isn’t good at this time of year. To James’s disappointment, the trip doesn’t happen.

The plot here is incidental. Instead, the narrative technique stands out. The story’s point of view shifts continually from one character to the other. Mixed in with observations about what’s happening in the real world, we get inklings of their thoughts and mental chatter.

The second part is shorter and has a different style. Rather than shifting voices, an abstract narrator describes the passage of time. The Ramseys neglect the estate. In parenthetical asides, we learn Mrs. Ramsey has died. One of their sons, Andrew, is killed in World War I and a daughter, Prue, dies in childbirth. The “protagonist” (if there can be such a thing in this novel) of this section is the Ramsay’s housekeeper, who strives to keep the estate from complete ruin.

Part three returns to the style, tone, and length of the first part. The reduced family returns to another vacation at the estate ten years later. Mr. Ramsey, James, and his sister Cam finally embark on the much-postponed visit to the Lighthouse, while Lily stays behind, struggling to complete her painting.

Andrew and Cam both resent their father, who is beset with grief and needing validation. They have a breakthrough on the way to the Lighthouse, coming to understand and appreciate each other and what has been lost. Lily completes her painting, realizing that it doesn’t matter as much as the reflection that went into it.

Audiovisual

Music: George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and An American In Paris and Ella Fitzgerald singing the Gershwin songbook. All have long been part of my music collection: I was glad to revisit them now.

Arts: Gioia recommended another pair of overly-familiar painters: Frida Kahlo and Edward Hopper. I knew both artists’ work and have seen their most important paintings IRL, so I didn’t revisit them this week.

](/assets/images/2025/11/hopper-new_york_restaurant.jpg)

New York Restaurant (1922) by Edward Hopper via Wikimedia

Cinema: Martin Scorcese’s RAGING BULL (1980), one of the most painful films I’ve seen. Robert De Niro plays 1940s boxing superstar Jake LaMotta, whose troubled inner world led to a disastrous personal life.

I’ve never liked boxing, and this movie is a graphic depiction of that brutal “sport” — and a deeply disturbing document of domestic violence. By the time of LaMotta’s nadir in a prison cell, I’d unwittingly placed my hands at the sides of my head. Gut-wrenching.

Reflections

I had a go at Woolf’s Orlando a few years ago and stopped about a fourth of the way into it. I found To the Lighthouse equally challenging. By the end of part one, I wondered whether I’d be able to finish. To be clear, Woolf is an incredible writer: I just found the approach too disorienting. But that’s the point. Some things can’t be accurately conveyed in a “logical” linear sequence.

I’m dazzled by writers and artists who can express ideas and feelings by transcending established narrative forms. But that doesn’t mean I enjoy their works. Several weeks later, I’m still thinking about JEANNE DIELMAN, 23 QUAI DU COMMERCE, 1080 BRUXELLES. I didn’t enjoy that film, but it did make me think. And it made me think precisely because it violated my expectations of how the medium of cinema is supposed to work.

That was also the case with this week’s readings. I appreciated them, but didn’t like them. I’ve never had a problem with modernist paintings, but I know many people don’t connect with them, since they don’t comport to expectations of what painting is supposed to do. Sometimes, transcending a medium’s conventions is how you get the point across. But you can only do that so many times before the exception becomes the norm — and the audience tunes out.

Notes on Note-taking

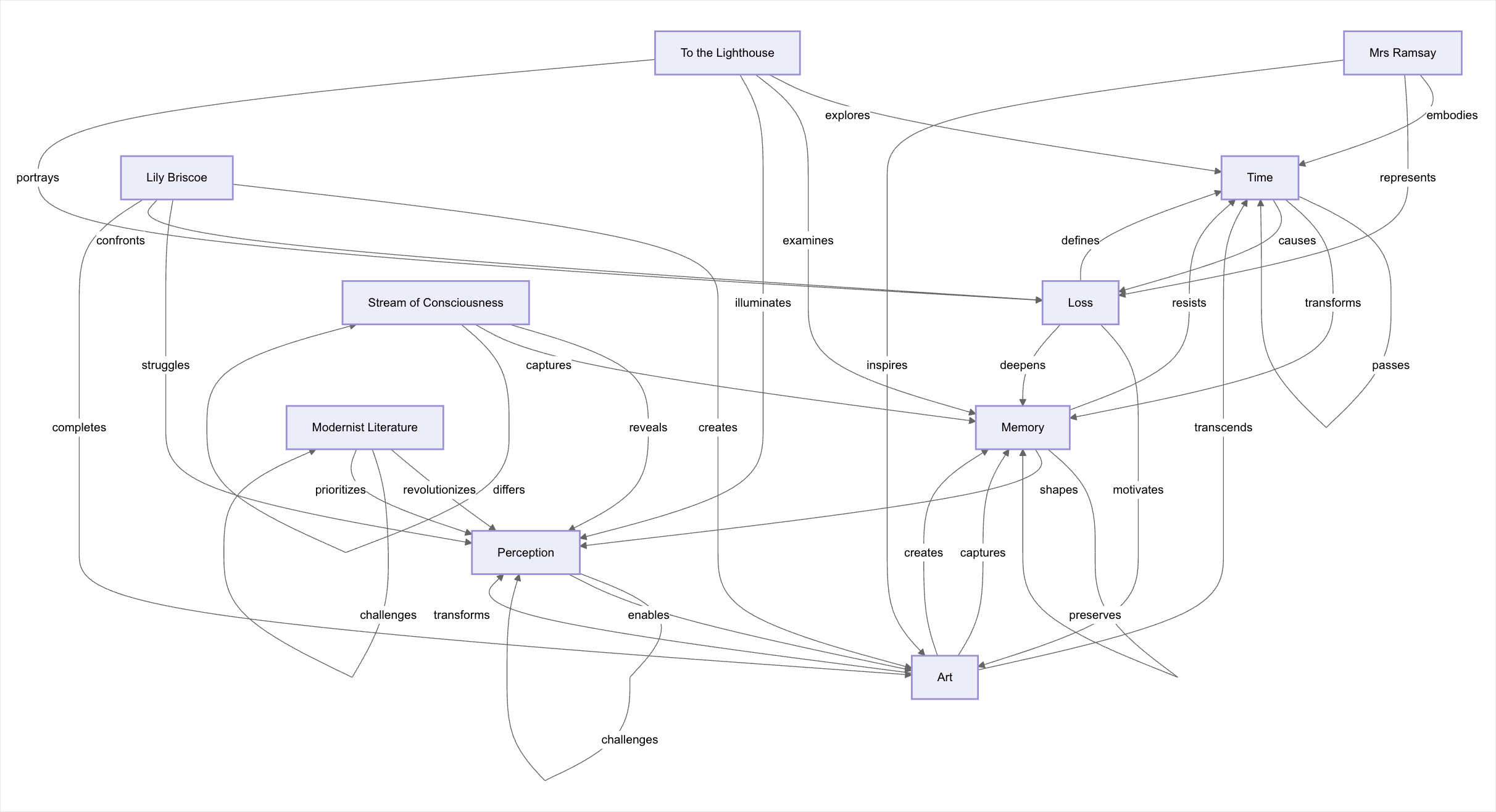

Last year, I shared an AI-powered concept mapping tool called LLMapper. I developed that until it got good enough and then stopped. But when Anthropic announced Agent Skills, I decided to revisit LLMapper to see if it could be turned into a Skill so anyone can use it within Claude. The results exceeded my expectations. Here’s a concept map it drew of To the Lighthouse:

An AI-generated concept map of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse

After the user provides the source material (in this case, the URL for the novel’s Wikipedia page,) Claude asks which of three focusing questions they’d like the map to explore. In this case, it offered these questions:

FOCUSING QUESTION 1:

How does To the Lighthouse challenge traditional narrative structure and advance modernist literary techniques in ways that reshape our understanding of consciousness and human experience?FOCUSING QUESTION 2:

What does Woolf’s exploration of gender roles, Victorian family dynamics, and the emerging “modern woman” reveal about changing social structures in early 20th century Britain?FOCUSING QUESTION 3:

How does the novel’s treatment of time, memory, and loss illuminate the relationship between art, perception, and the human struggle to find meaning in everyday life?

Even perusing the focusing questions is useful. I selected the third, and the resulting diagram helped me better understand the key themes of time, memory, and loss as seen through the lens of individual perception.

Making concept maps helps visual thinkers like myself understand challenging concepts differently. Of course, LLMapper makes the diagram for you, so you lose some of its inherent value. But it’s still illuminating as an object of study and critique. Because this is happening within a chatbot, it’s possible to ask for changes and elaborations. That, in itself, has proven valuable.

The LLMapper Skill is available on Github if you want to try it yourself. (You’ll need a Pro, Plus, or Enterprise account, or Claude Code.) This video has a short demo and walks you through the installation process:

Up Next

Gioia recommends two writings by Freud: An Outline of Psychoanalysis and Beyond the Pleasure Principle. My sense is his work is now considered to have more historical than clinical value, but that might be wrong. I look forward to engaging with this influential thinker.

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!