The theme for week 38 of the humanities crash course was emergence. Specifically, I read two classics that argue for bottom-up responses to dynamic situations. I also watched a movie that exemplified one of these texts — and is sadly relevant today for more than one reason.

Readings

Let’s start with the texts: John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty and Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. They’re contemporaries: both books came out in 1859. Somehow I’d always assumed Mill influenced the U.S. founders. Wrong! Still, it’s one of the key works underlying modern liberal societies.

Mill argues that individual liberty is essential for societies and individuals within them. He introduced the “harm principle”: the idea that the only constraint on individual liberty should be causing harm to others (either directly or through neglect.) That is, you should be free to do as you will as long as others don’t get hurt.

Not only is this morally right, it also helps society as a whole. No one individual — not even those in charge — has a monopoly on the truth. Accommodating a diversity of voices allows societies to explore more than approach to challenges.

This only works, of course, if people are free to speak their minds. Mill introduced the then-radical idea that individuals should be allowed to share all sorts of ideas, even those that might be considered repugnant, harmful, or false. (But, importantly, not speech that incites harm.)

Mill worried about social pressure: what he called the “tyranny of the majority.” Only by allowing divergence from mainstream views would societies be able to experiment with other approaches. Today, we’d consider Mill a systems thinker: he seems to call for requisite variety avant la lettre.

Of course, that doesn’t mean societies should be free-for-alls. Mill acknowledges there’s a role for authority, but it shouldn’t impinge upon personal freedoms. As noted above, he draws the line at harming others. Also, balancing dynamism and stability calls for shared cultural foundations. He called for education as a means to developing autonomous individuals.

On the Origin of Species is one of the most influential science books ever written. It introduced the idea of Natural Selection: species don’t emerge fully formed but change gradually over time. Even today, this sounds radical to people reared to believe in God as the creator of the universe.

So Darwin lays out his argument carefully and gradually. He draws an analogy with a process his audience understood: selective breeding of plants and animals by humans. Domesticated species have characteristics chosen by human breeders, who determine which specimens to breed.

Nature, he argues, does something similar: specimens whose characteristics make them likely to survive are the ones who reproduce. Those without such characteristics don’t leave as many offspring. Over time, this process produces species that are better adapted to their environment.

Darwin is a good writer and obviously passionate about his subject. He comes across as a genuine nerd. Gioia recommended reading only the first four chapters, and that’s where I stopped. But I may finish it sometime: there’s some technical material but also lovely descriptions of animals and plants.

Audiovisual

Music: Waltzes by Johann Strauss II, Frédéric Chopin, and Bill Evans. Of course, the first two are very familiar. I’d heard Evans’s work with Miles Davis, but not his waltzes, so that was new to me.

Gioia also recommended waltzes by John Coltrane, but I chose to skip them: Coltrane requires more active listening than I was able to muster this week.

Arts: two comprehensive styles from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries: Art Nouveau and Art Deco. By “comprehensive,” I mean they spanned more than one medium. By “style” I mean that I’ve always seen them as superficial responses to their context.

Both dealt with the impact of industrialization and the historicist/classicist aesthetics that dominated the first parts of the 19th Century. Art Nouveau adopted organic forms. After World War I, that style had become passé, leading to the emergence of Art Deco, which adapted more industrial forms.

](/assets/images/2025/09/paris-metro-entrance.jpg)

Photo by Bellomonte - Own work, CC0, via Wikimedia

Cinema: Alan J. Pakula’s ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN (1976.) Although Pakula directed, but this is in many ways Robert Redford’s film: he not only acted in it, but his company produced it and he encouraged the book on which it’s based. Redford died last week, so I thought it appropriate to watch one of his films.

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN seemed the most apt given this week’s theme. The film tells the real-life story of how Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein investigated the conspiracy behind the Watergate break-in that led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation.

This might sound boring, but the screenplay (by William Goldman), acting, direction, design, etc. make it thrilling. Talk about social pressure: these were relative nobodies exposing powerful forces. Both them and their paper persisted in searching for the truth despite very real and present threats.

Reflections

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN isn’t about politics; it’s about integrity and freedom of speech. This makes it perennially relevant. Last week provided a contemporary example: the indefinite suspension by ABC of their late-night host Jimmy Kimmel after he made a politically inflammatory joke on air.

Some voices on the left cried foul. Kimmel’s suspension might look like the network is preemptively self-censoring to avoid larger consequences, such as threats of regulatory pressure from the current right-wing U.S. administration, legal challenges, or public outcry. (Although there may be more to it than that.)

Of course, the drive to censor “unacceptable” voices isn’t limited to one side of the political spectrum. Some on the left are also keen on censoring speech. When I first announced this Substack, several people (on Bluesky, where discussions tend to lean left) questioned my choice of platform. Didn’t I know, they wondered, that Substack has refused to censor views they don’t like?

I tend to side with Mill: free speech matters — and “free” means allowing for views I might find objectionable. If I’ve learned one thing from this course, it’s humility. The breadth of human experience is rich, deep, and diverse. There are many paths to truth — and blind alleys, too.

And here we get back to emergence. Darwin’s idea was powerful because it explained how order — in this case, the balanced relationship between creatures and their environments — emerges without top-down controllers. This was Mill’s goal as well: enabling societies and individuals to evolve and prosper with minimal coercion. Rather than natural selection, his means was acting and speaking freely, within reasonable bounds.

Does that mean anything goes? No. As Mill suggested, speech that incites harm is out of bounds. That might include what we now call “hate” speech, a category he wouldn’t have recognized. (“Hate” speech can be tricky, since those in power will look to control discourse by defining what’s hateful.)

Is Mill’s approach still valid? After all, he lived before mass media or the internet. (One of the pleasures of watching ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN in 2025 is seeing reporters scrambling to do their information-centric jobs using only rotary phones, steno pads, and mechanical typewriters.)

Our words and actions have wider reach today than they would’ve in the 19th century. Today, where to draw the line on acceptable speech is a tricky question that evokes Popper’s paradox of tolerance: unlimited tolerance, especially toward those who refuse rational discourse, can undermine tolerance itself.

Notes on Note-taking

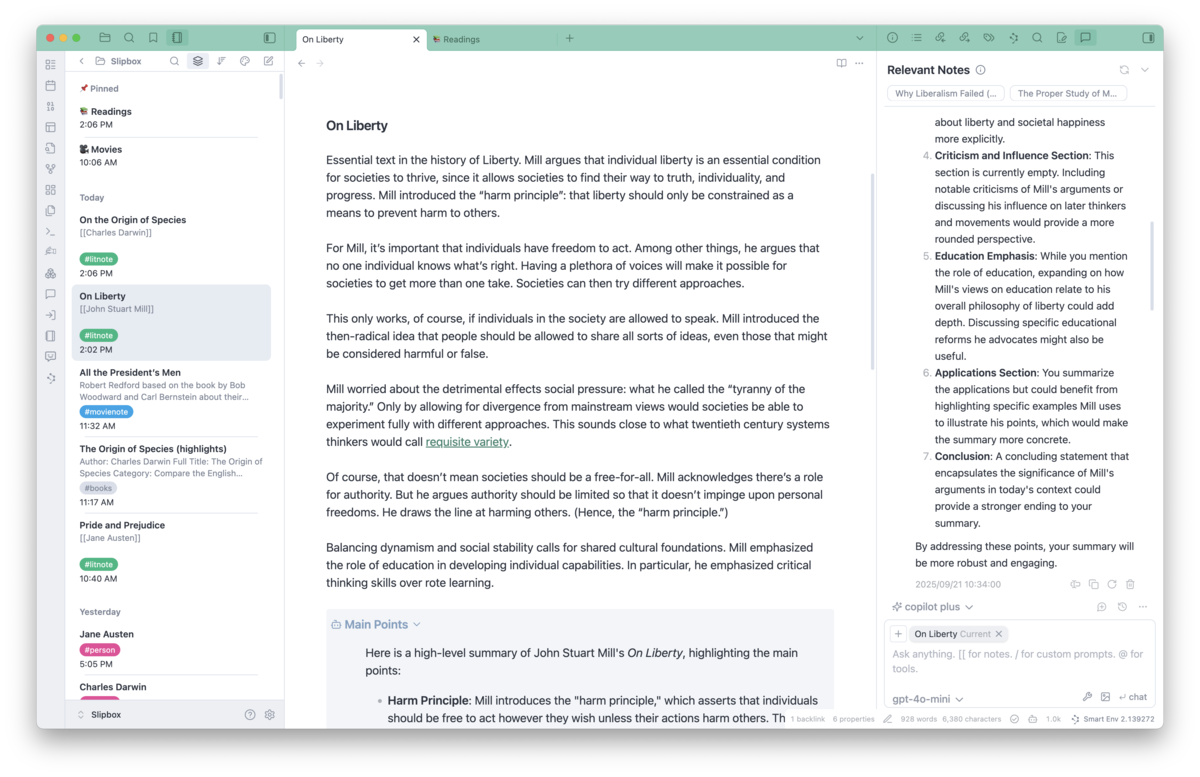

This week, my main progress from a tooling perspective might seem relatively superficial: I installed a couple of plugins that changed Obsidian’s user interface to make it more pleasant and usable.

First, I activated Minimal Theme. I’m using it primarily to color-code my vaults: green for my Slipbox vault, where I explore readings and such, and blue for my Projects vault, where I keep client stuff. The tinted header lets me see at a glance which vault I’m in.

The second plugin, Notebook Navigator, is more impactful. It changes how I navigate notes in both vaults. Rather than present a traditional file-folder panel, it offers a customizable “flat” pane that lists all notes in a way that highlights relevant information (such as differentiating different kinds of notes.)

Although these are primarily cosmetic changes, they’ve transformed my Obsidian experience. I’m finding the new UI much more pleasant to work with, which is making time spent in my knowledge garden much more pleasurable. Big win!

Up Next

We’re entering the last week of the course’s third quarter. Gioia recommends a wide assortment of readings: selected poems by Emily Dickinson, Poe’s The Raven and The Fall of the House of Usher, Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener and chapter one of Moby Dick, Thoreau’s Walden, chapter’s 1–6 of Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and Whitman’s Song of Myself. Whew!

I’ve already read all of these with the exception of the works by Poe. I’ll tackle these two and might revisit Walden. But I might also make space this week for something completely different — I haven’t yet decided what. (But it likely won’t be more verse!)

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!