In week 28 of the humanities crash course, I read sections of two foundational works of art history: The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini and four biographies from Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists.

Gioia recommended the first eighteen chapters of Cellini’s autobiography and five of Vasari’s biographies. I read Vasari in college and Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo Da Vinci a few years ago, so I decided to skip Da Vinci’s. (Mostly to make space for work-related reading — no slacking!)

I paired these stories of Renaissance geniuses with a work by a more contemporary artist: Soviet film director Andrei Tarkovsky.

Readings

The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini relates the life of Italian goldsmith, sculptor, and artist Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571). The book offers a firsthand take on the artistic and political milieu of the time from an active (and somewhat roguish) participant.

As suggested by Gioia, I only read the first eighteen chapters, which cover Cellini’s background and early years, including his education and apprenticeship. He gets into scruffs and disagreements over commissions, and isn’t beyond pulling daggers on his enemies.

The Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) offers short biographies of painters, sculptors, and other artists of the Italian Renaissance and assessments of their works. In some cases, the people profiled were Vasari’s contemporaries.

Parts of the Lives are factual — e.g., birth dates, apprenticeships, etc. — while others are anecdotal. Vasari has lots of opinions, although not always varied — i.e., most works are either “beautiful” or “extremely beautiful.”

The book features celebrated episodes in the artists’ lives, some of which have become part of their mythology. For example, it includes the following story about Michelangelo sculpting the David, which I’ve re-told many times:

Around this time it happened that Piero Soderini saw the statue, and it pleased him greatly, but while Michelangelo was giving it the finishing touches, he told Michelangelo that he thought the nose of the figure was too large. Michelangelo, realizing that the Gonfaloniere was standing under the giant and that his viewpoint did not allow him to see it properly, climbed up the scaffolding to satisfy Soderini (who was behind him nearby), and having quickly grabbed his chisel in his left hand along with a little marble dust that he found on the planks in the scaffolding, Michelangelo began to tap lightly with the chisel, allowing the dust to fall little by little without retouching the nose from the way it was. Then, looking down at the Gonfaloniere who stood there watching, he ordered:

‘Look at it now.’

‘I like it better,’ replied the Gonfaloniere: ‘you’ve made it come alive.’

Thus Michelangelo climbed down, and, having contented this lord, he laughed to himself, feeling compassion for those who, in order to make it appear that they understand, do not realize what they are saying

These are the four biographies I re-visited at this time:

-

Giotto was an evolutionary figure that helped art move towards more naturalism after the flat, symbolic style of the previously dominant Byzantine art. Through his more naturalistic approach, he laid the groundwork for the Renaissance painters to follow.

-

Sandro Boticelli focused on mythological themes, with an emphasis on beauty, elegance, and grace. Vasari describes some of his famous paintings, such as The Birth of Venus, making me wish the book had pictures.

-

Raphael, like many of these other artists, was a child prodigy who developed into a master of form and composition. His work is celebrated for its classical beauty and naturalism. He was a rival of Michelangelo.

-

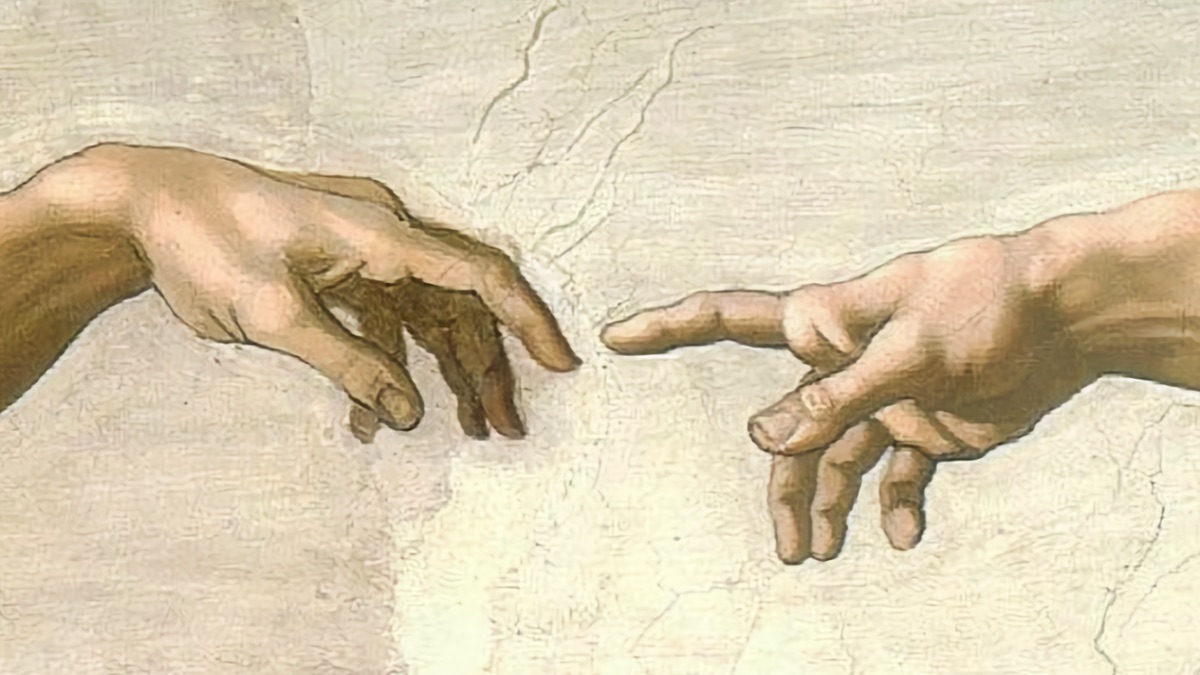

Michelangelo, perhaps the most important artist in history. Vasari — who was a collaborator — elevates him to divine status for his mastery in several arts: painting, sculpture, and architecture.

.jpg)](/assets/images/2025/07/creation-of-adam-full-detail.jpg)

The Creation of Adam (detail) by Michelangelo Buonarrotti via Wikimedia

As I mentioned in the intro, I skipped Leonardo’s biography at this time. Suffice it to say, he was an even more impressive genius than the others highlighted here. Besides being an excellent painter (one of the best who ever lived,) he was also an inventor, engineer, and natural scientist. A true polymath and the prototypical “Renaissance man.”

Audiovisual

Music: works by Josquin des Prez and Guillaume de Machaut. I hadn’t heard of either composer or their work. They evoke the contemplative style of Gregorian chant but with multiple interweaving voices — medieval-sounding but with a Renaissance edge.

Arts: appropriately, I examined Leonardo Da Vinci’s notebooks — not their substance (which would require more time than I had available this week) but their form. I found this video of Adam Savage perusing a modern replica most enlightening:

If the word genius applies to any one human being, Da Vinci is the person. These books are a key part of his extended mind. Seeing them — even vicariously — is inspiring.

Cinema: Tarkovsky’s MIRROR. I’d seen ANDREI RUBLEV and SOLARIS in college, and they bored me. So I was apprehensive going in. I shouldn’t have been. For one, I’m more patient now. But more importantly, this is a stunningly beautiful work, albeit one with an unconventional structure.

Tarkovsky struggled to get MIRROR made — more on this below. (Note-to-self: I must revisit Tarkovsky’s other movies now that I’m older and more open-minded.)

Reflections

A common theme in Vasari’s Lives is the key relationship between the artist and their patrons. Somebody must pay for artists to live and work. In the Renaissance, it was either a political or religious leader.

As a result, these geniuses couldn’t focus on whatever they liked. They worked exclusively on commission, and commissions either celebrated their patrons (through funerary monuments, for example) or religious themes.

Some artists achieved a high status. Their patrons recognized that their gifts could gild their own legacies, leading them to value artists and in some cases (e.g., Michelangelo) tolerate their petulance.

Still, these brilliant people weren’t free. They couldn’t imagine new ways of being. The best they could do was explore stylistic variations and forms to express narrow themes.

That approach led to some of the most impressive and important artworks ever produced. Constraints liberate. But I couldn’t help wonder, what would Michelangelo have created if he wasn’t under the Pope’s yoke?

Tarkovsky, too, was under the yoke — in his case, of an oppressive socioeconomic system. As Wikipedia notes, “[he] devised the original concept [for MIRROR] in 1964, but the Soviet government did not approve funding for the film until 1973 and limited the film’s release amid accusations of cinephilic elitism.”

Soviet commisars only approved the production under strict constraints: “a budget of 622,000 Rbls and 7,500 metres (24,606 feet) of Kodak film, corresponding to 110 minutes, or roughly three takes, assuming a film length of 3,000 metres (10,000 feet).”

But then, “in July 1974, after Tarkovsky finished the film, [Head of the State Committee for Cinematography Filipp Ermash] rejected it as incomprehensible. Infuriated by the rejection, Tarkovsky toyed with the idea of making a film outside the Soviet Union. Goskino ultimately approved Mirror without any changes in fall 1974.”

Can you imagine being a genius trying to create anything — much less a personal statement that entails a complex production — under such conditions? Given scraps to work with and having the finished product rejected by political ideologues. Appalling.

Which is to say, this week’s readings reminded me that even with its flaws, a relatively free market (both economic and ideological) is preferable to one controlled by gatekeepers. One need only learn about our brilliant ancestors’ struggles with Popes, dukes, and commisars to know we don’t want to revert to groveling to create things of worth.

Notes on Note-taking

This week’s readings were old biographies of famous artists. I’m restating that because it affected how I used my notes to think about them.

When I read Shakespeare in weeks 26–27, the central object of interest was the thing I was reading — Hamlet, King Lear, The Tempest. In contrast, this week’s texts were narratives about the lives of artists. While Vasari’s Lives has value as literature per se, it’s not as important as Boticelli’s Birth of Venus or Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos. One needn’t learn about these men at all to appreciate their works — and their works are what matter here.

And if one wants to learn about the artists, there are modern — and perhaps better — biographies, such as Isaacson’s Leonardo Da Vinci. (In particular, Vasari doesn’t cover his subjects’ sexual orientation, a topic of interest to modern readers.)

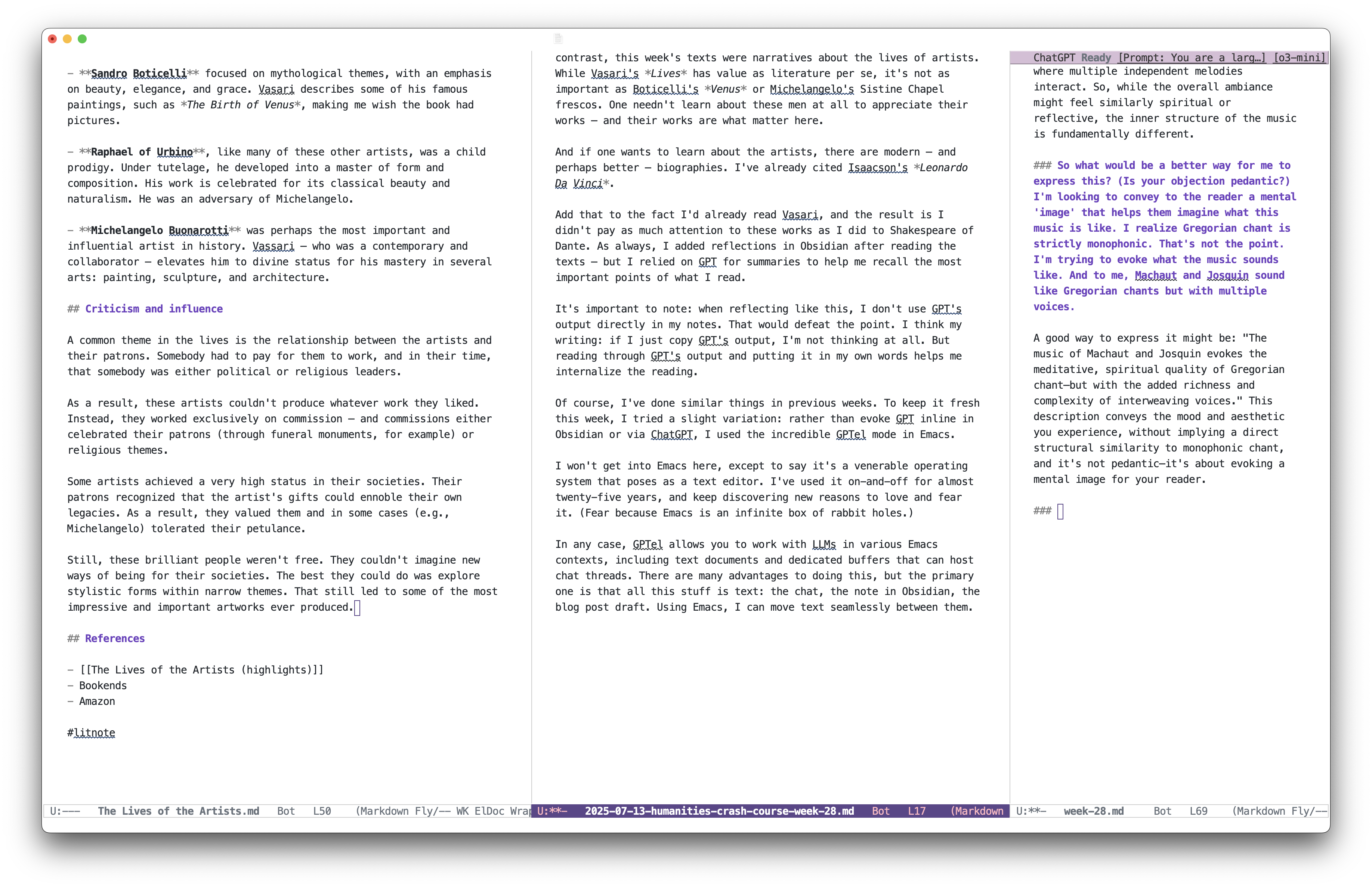

Add that to the fact I’d already read Vasari, and the result is I didn’t pay as much attention to these works as I did to Shakespeare of Dante. As always, I added reflections in Obsidian after reading the texts — but I relied on GPT for summaries to help me recall the most important points of what I read.

It’s important to note: when reflecting like this, I don’t use GPT’s output directly in my notes. That would defeat the point. I think by writing, and if I just copy GPT’s output, I’m not thinking. But reading through GPT’s output and putting it in my own words helps me internalize the material.

Of course, I’ve done similar things in previous weeks. To keep it fresh, I tried a slight variation now: rather than evoking GPT inline in Obsidian or via ChatGPT, I used the gptel package in Emacs.

I won’t get into Emacs here, except to say it’s a venerable operating system that poses as a text editor. I’ve used it on-and-off for almost twenty-five years and keep discovering new reasons to love and fear it. (Fear because Emacs is an infinite box of rabbit holes.)

In any case, gptel allows you to work with LLMs in various Emacs contexts, including text documents and dedicated buffers that can host chat threads. There are many advantages to doing this, but the main one for me is that all this is text: the chat, the note in Obsidian, the blog post draft. Using Emacs, I can move — and evoke LLMs — seamlessly between them.

Three buffers in Emacs. From left to right: an Obsidian note, a blog post draft, and at gptel conversation.

There’s more to tell here, and perhaps someday I will. Suffice it to say, I’ve long considered moving much of my computing life to Emacs. After a quarter century using the software, I’ve internalized its idiosyncracies and keybindings. But I keep pulling back from the edge, concerned that this uber-powerful tool would swallow up my time.

Up Next

Gioia recommends one final pass at Shakespeare: Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 and Othello. I read both parts of Henry IV in 2023 and won’t re-visit them now. Instead, I plan to tackle two other plays: The Merchant of Venice and Julius Caesar.

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!