The end of June means we’re at the halfway point of the humanities crash course. This week, I read three tragedies by William Shakespeare: Hamlet, Macbeth, and King Lear. I’d already read the first two and had seen a cinematic adaptation of the latter, but I revisited all three anyway. Like verse, I’ve always found plays harder to read than prose. But this time I found it much easier — indeed, pleasurable — by using a dedicated app. More on this below.

Readings

Hamlet, Macbeth, and King Lear are among Shakespeare’s most celebrated plays — with good reason: they use exquisite language and word play to plumb the depths of human psychology. They date from the first six years of the 17th century, so unlike the Canterbury Tales, their English is close enough to ours’ to make them easy to follow. Here’s a brief synopsis.

Let’s start with Hamlet, perhaps the most important and influential play ever written — and with good reason. Hamlet is prince of Denmark. His father, King Hamlet, has died. Shortly after, his mother, Queen Gertrude, weds his uncle and new king, Claudius. The old king’s ghost tells Hamlet that Claudius murdered him. He asks for revenge.

Although enraged, Hamlet struggles with the decision to avenge his father’s death. Is the ghost reliable or a trickster demon? Hamlet frets and becomes increasingly erratic. Others blame his apparent madness on unrequited love for Ophelia.

Hamlet devises a way of validating the ghost’s story: he incites a troupe of actors to perform a play for the king and queen that echoes the circumstances of his father’s alleged murder. He and his friend Horatio observe Claudius’s reactions. He leaves the play in a rage, confirming the ghost’s story.

In a rage, Hamlet confronts his mother and murders Polonius, Ophelia’s father. Ophelia descends into madness. Laertes, her brother, learns of Hamlet’s deed. He conspires with Claudius to kill Hamlet. The opportunity comes when Ophelia dies (possibly at her own hand): at her funeral, Hamlet and Laertes come to odds, ending in a rigged duel. Everyone but Horatio dies.

Like Hamlet, Macbeth also centers on regicide. Macbeth is a general serving Duncan, king of Scotland. Three witches prophesy that Macbeth will gain the crown, nut also issue three cryptic conditions. For example, they tell him he won’t be defeated by any man born of a woman.

He tells his wife about the prophecies. She encourages him to murder Duncan while he’s a guest in their house. At first horrified by the thought, Macbeth is brought over by the witches’ prophecies, which imply his immortality. He murders Duncan in his sleep.

Macduff, one of Duncan’s generals, is in England. Macbeth has his family murdered in their home. When Macduff learns of this, he’s convinced to march on Macbeth with the English army.

Lady Macbeth’s guilty conscience won’t let her sleep. She descends into madness. The English invade. Lady Macbeth dies, possibly a suicide. When cornered by Macduff, Macbeth clings to the prophecy — but Macduff informs him that he was born through a Cesarian, so ”unnaturally.” Macduff decapitates Macbeth. Heavy stuff!

King Lear doesn’t ease up. Lear is the King of Britain in mythic times, before Christ. An old man, he decides to divide his kingdom among his three daughters, Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia. The first two are married (to the Dukes of Albany and Cornwall, respectively.) Cordelia, the youngest, is unmarried, but two suitors court her.

Lear unwisely elicits affectionate speeches from them in exchange for their inheritance. The older sisters fawn over the old man. Cordelia sees through their superficiality and refuses to play. Lear disinherits her, and one of her suitors, the Duke of Burgundy, drops is courtship. The other, the King of France, takes her for a wife.

The Earl of Gloucester, a friend of Lear’s, has two sons: Edgar and Edmund. Unbeknownst to Gloucester, Edmund is deeply resentful since he was born out of wedlock. He conspires to steal his older brother’s inheritance by convincing their father that he’s conspiring to kill him.

No sooner do Regan and Goneril come into their inheritance that things go south. They renege on their promises to allow their father a retinue. His party whittles down to his friend the Earl of Kent, in disguise after Lear banishes him for standing up for Cornelia, and his Fool. The fool keeps pointing out that all this mischief is Lear’s own doing.

As Lear, the Fool, Kent, and Edgar — disguised as a madman — wander around in a violent storm. The others conspire against Lear. Betrayed by Edmund, Gloucester is accused of treason after helping Lear escape. In a deeply disturbing scene, Cornwall plucks out his eyes.

Cordelia, under the auspices of France, invades. As the two armies battle, things descend into chaos. Regan and Goneril fight over Edmund’s affection. France loses the war, and Lear and Cordelia are captured. The latter is hanged. Lear spirals into madness and dies. Most characters die, either at their own hand or through treachery or violence.

These are disturbing topics and Shakespeare doesn’t spare the audience. But the plays are leavened with enough humor and violence to make them engaging and lively. These works don’t come across as exclusively moralistic: they’re meant as entertainment.

Audiovisual

Music: Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and three works inspired by these readings: Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn’s Such Sweet Thunder and Shostakovich’s Hamlet and King Lear film soundtracks. I enjoyed the Berlioz and Ellington but found the Shostakovich forgettable.

Arts: Titian, in particular his Bacchus and Ariadne:

](/assets/images/2025/06/bacchus-and-ariadne.jpg)

Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne - National Gallery, London, Public Domain via Wikimedia

This short lecture explains the painting in detail:

Titian is looking to convey the inner life of his characters. And even though the painting focuses on two of them, the whole really works as a composition that includes several characters, who are also richly detailed, even if they’re not the work’s focus. In this, it’s similar to Shakespeare’s plays.

Cinema: there are many cinematic adaptations of these works. A favorite of mine is Kurosawa’s RAN. Rather than revisit that now, I sought out an actual theatrical performance of the play I was least familiar with: King Lear. YouTube has a good one starring Laurence Olivier:

Reflections

A common theme runs through these plays: there’s legitimate (“natural”) order to leadership succession and a price to pay if you go against that order. That theme is most vibrant in Macbeth: he takes matters into his own hands (literally) by murdering the monarch to take his place. Claudius usurps Hamlet Senior’s throne and wife. Regan and Goneril sidetrack Lear.

Everyone has agency — and sometimes use it to subvert the natural order. In every case, the ploy backfires. You may trick others but you can’t trick yourself. Conscience gets you in the end — and if it doesn’t, karma will. But from where these characters stand, the right thing to do isn’t always obvious. Hamlet, in particular, struggles with self-doubt.

As I read these deeply considered and insightful works of literature, I thought of this recent post by Elon Musk:

We will use Grok 3.5 (maybe we should call it 4), which has advanced reasoning, to rewrite the entire corpus of human knowledge, adding missing information and deleting errors.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) June 21, 2025

Then retrain on that.

Far too much garbage in any foundation model trained on uncorrected data.

I’ve worked with LLMs long enough to know that if you ask for corrections, it will find stuff to correct. What would Grok 3.5 (or 4, as Musk would have it) “fix” in Shakespeare? What “errors” would it spot? What “missing information” would it supply?

One might caricature this post as a typical manifestation of a particular kind of “tech” mindset, which values disruption for its own sake. Old is bad — ineffectual, superstitious drivel in need of correction. Of course, assuming old = flawed isn’t unique to tech disruptors. Here’s Goneril:

Idle old man,

That still would manage those authorities

That he hath given away! Now, by my life,

Old fools are babes again; and must be used

With cheques as flatteries,—when they are seen abused.

Remember what I tell you.

Deep in the disruptors’ ethos is the conviction that they can do better — where “they” here is a very small group of smart people. But it’s a particular kind of smart that only operates along a few dimensions and can manifest a limited understanding of human nature and wisdom — plus sometimes, greed and/or resentment. The result? Edmund-like characters desperately pushing to overthrow the established order, either for its own sake or to get themselves on top.

Notes on Note-taking

Ok, enough crapping on the disruptor mindset. I’m no luddite; disruption can have upsides. One such is giving us new ways to experience old masterpieces.

I’ve read Shakespeare before. Back in school, it was on paper. But most recently, I’ve used the Kindle app. Both books and ebooks are effective at conveying Shakespeare’s words. But these works require a bit of context and explanation to get the meaning behind the ornate and and sometimes obscure language.

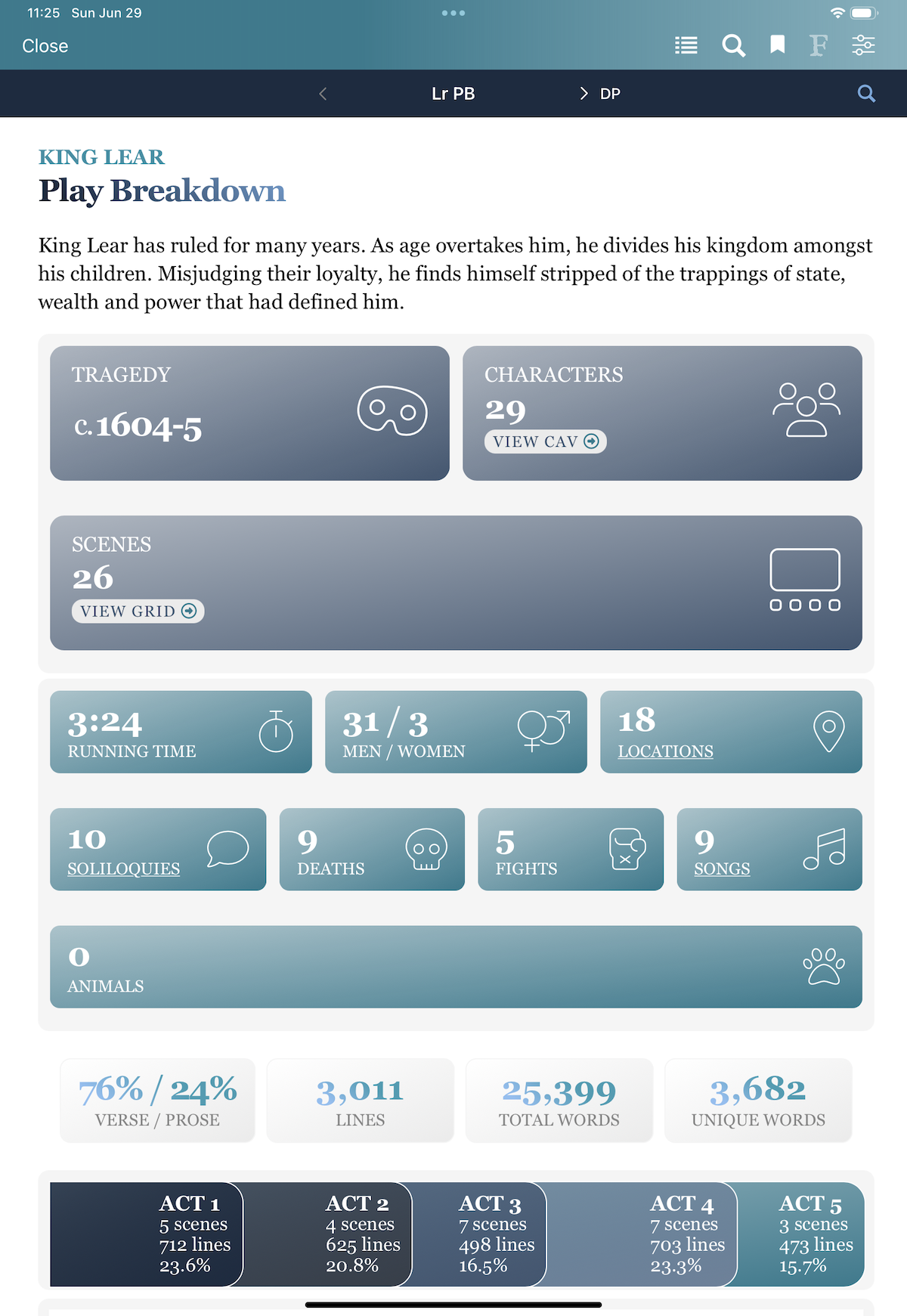

This week, I tried something different and it led to the best experience I’ve ever had reading Shakespeare. Rather than read on paper or a traditional ebook, I used a dedicated app called Shakespeare Pro. It’s available for Apple and Android platforms; I used it on my iPad and iPhone.

It felt like next-gen reading. The app includes the plays’ text, of course. But it also includes lots of ancillary materials, such as character summaries (dramatis personae,) explanations of each scene and each act, detailed analyses of each play, etc.

One feature I found especially useful was the visual summary of each act’s length, which allowed me to pace my reading. Given three plays, I realized that reading two to three acts per day would allow me to get through the three plays comfortably in a week.

The experience of reading the plays themselves is also excellent. Most ebook readers paginate texts to simulate the experience of reading a book. With Shakespeare Pro, you scroll through the text — an experience I found easier to follow due to the formatting particularities of plays. Speaking of, the formatting of text is consistently thoughtful. (I realize the Kindle app can also be set to scroll rather than paginate, but I always keep it in pagination mode.)

That said, the app isn’t perfect. There are two features I missed: the ability to sync highlights and annotations to Obsidian via Readwise and more choice in fonts. And of course, this experience is limited to Shakespeare’s works. I imagine reading the Bible in a similarly dedicated app would be useful — but it’s not a system that can be generalized to any text.

That said, if you plan to read several of Shakespeare’s works, the Shakespeare Pro app is well worth it. It’s a vastly superior experience than reading on paper or a general ebook reading app or device.

Up Next

More Shakespeare! Gioia recommends Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest, and Romeo and Juliet. I’ve only read the latter, and that was decades ago, in high school. I’m excited to revisit these classic works now.

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!