In week 16 of the humanities crash course, I revisited the Tao Te Ching and The Art of War. I just re-read the Tao Te Ching last year, so I only revisited my notes now. I’ve also read The Art of War a few times, but decided to re-visit it now anyway.

Readings

Both books are related. The Art of War is older; Sun Tzu wrote it around 500 BCE, at a time when war was becoming more “professionalized” in China. The book aims convey what had (or hadn’t) worked in the battlefield.

The starting point is conflict. There’s an enemy we’re looking to defeat. The best victory is achieved without engagement. That’s not always possible, so the book offers pragmatic suggestions on tactical maneuvers and such.

It gives good advice for situations involving conflict, which is why they’ve influenced leaders (including businesspeople) throughout centuries:

- It’s better to win before any shots are fired (i.e., through cunning and calculation.)

- Use deception.

- Don’t let conflicts drag on.

- Understand the context to use it to your advantage.

- Keep your forces unified and disciplined.

- Adapt to changing conditions on the ground.

- Consider economics and logistics.

- Gather intelligence on the opposition.

The goal is winning through foresight rather than brute force — good advice!

The Tao Te Ching, written by Lao Tzu around the late 4th century BCE, is the central text in Taoism, a philosophy that aims for skillful action by aligning with the natural order of the universe — i.e., doing through “non-doing” and transcending distinctions (which aren’t present in reality but layered onto experiences by humans.)

Tao means Way, as in the Way to achieve such alignment. The book is a guide to living the Tao. (Living in Tao?) But as it makes clear from its very first lines, you can’t really talk about it: the Tao precedes language. It’s a practice — and the practice entails non-striving.

Audiovisual

Music: Gioia recommended the Beatles (The White Album, Sgt. Pepper’s, and Abbey Road) and Rolling Stones (Let it Bleed, Beggars Banquet, and Exile on Main Street.)

I’d heard all three Rolling Stones albums before, but don’t know them by heart (like I do with the Beatles.) So I revisited all three. Some songs sounded a bit cringe-y, especially after having heard “real” blues a few weeks ago.

Of the three albums, Exile on Main Street sounds more authentic. (Perhaps because of the band member’s altered states?) In any case, it sounded most “in the Tao” to me — that is, as though the musicians surrendered to the experience of making this music. It’s about as rock ‘n roll as it gets.

Arts: Gioia recommended looking at Chinese architecture. As usual, my first thought was to look for short documentaries or lectures in YouTube. I was surprised by how little there was. Instead, I read the webpage Gioia suggested.

Cinema: Since we headed again to China, I took in another classic Chinese film that had long been on my to-watch list: Wong Kar-wai’s IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE. I found it more Confucian than Taoist, although its gently contemplative pacing, focus on details, and passivity strike something of a Taoist mood.

Reflections

When reading the Tao Te Ching, I’m often reminded of this passage from the Gospel of Matthew:

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon.

Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment?

Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they?

Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature?

And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin:

And yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.

Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to day is, and to morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith?

Therefore take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed?

(For after all these things do the Gentiles seek:) for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things.

But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.

Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.

The Tao Te Ching is older and from a different culture, but “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin” has always struck me as very Taoistic: both texts emphasize non-striving and putting your trust on a higher order.

Even though it’s even older, that spirit is also evident in The Art of War. It’s not merely letting things happen, but aligning mindfully with the needs of the time. Sometimes we must fight. Best to do it quickly and efficiently. And best yet if the conflict can be settled before it begins.

Notes on Note-taking

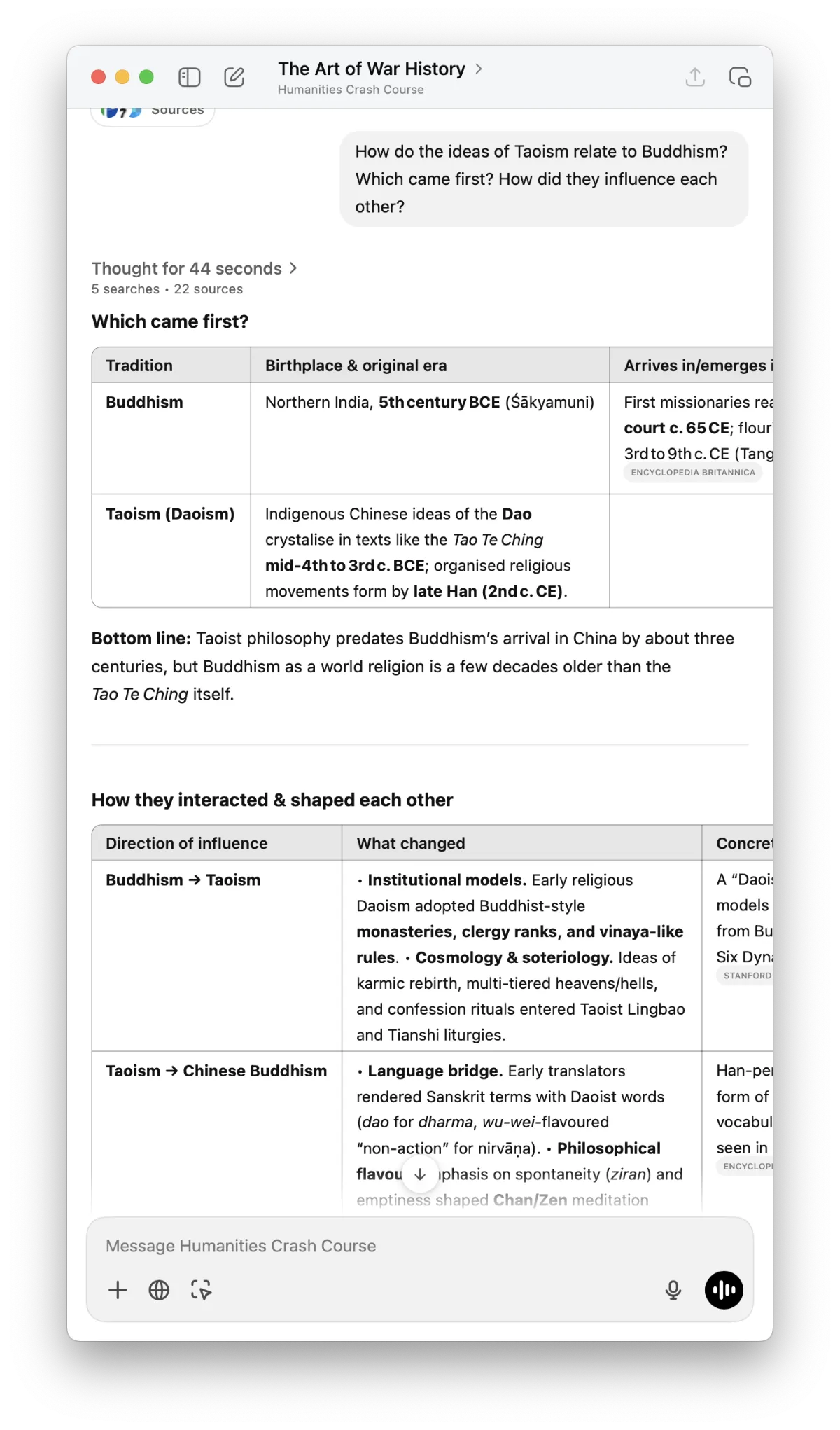

This week, I started using ChatGPT’s new o3 model. Its answers are a bit better than what I got with previous models, but there are downsides.

For one thing, o3 tends to format answers in tables rather than lists. This works well if you use ChatGPT in a wide window, but is less useful on a mobile device or (as in my case) on a narrow window to the side.

This is how I usually use ChatGPT on my Mac: in a narrow window. o3’s responses often include tables that get cut off in this window.

For another, replies take much longer as the AI does more “research” in the background. As a result, it feels less conversational than 4o — which changes how I interact with it. I’ll play more with o3 for work, but for this use case, I’ll revert to 4o.

Up Next

Gioia recommends Apulelius’s The Golden Ass. I’ve never read this, and frankly feel weary about returning to the period of Roman decline. (Too close to home?) But I’ll approach it with an open mind.

Again, there’s a YouTube playlist for the videos I’m sharing here. I’m also sharing these posts via Substack if you’d like to subscribe and comment. See you next week!