A version of this post first appeared in my newsletter. Subscribe to receive posts like this in your inbox every other Sunday.

Writing is an important part of many people’s work, including mine. It’s clear large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT can speed up the process, but how? I’m less interested in having the model write for me than in using it as a creative partner.

Writing isn’t just producing strings of words that convey some ideas. It’s also a way of thinking about stuff. Explaining ideas through writing helps clarify thoughts. Sometimes it’s straightforward: I have a clear, well-formed idea and start typing. But those cases are rare. More often, I have a vague notion. Or I have an idea but need a solid model or examples.

In these cases, talking with someone can help. I’ll bring up half-baked ideas in conversation, and my interlocutor will suggest angles I hadn’t considered. “Have you thought about this?” they’ll ask. Or they’ll say something like, “That reminds me of a story…”

These conversations often yield valuable nuggets. The person I’m talking with isn’t writing for me; they’re contributing pieces to a puzzle. The pieces come together when I sit in front of the computer to write. Gathering the pieces — curating the experience — is what the author does.

While LLMs can’t (yet?) assemble the puzzle, they can suggest pieces, with some reservations. So, I’m experimenting with using ChatGPT as a conversational partner. My prompts aren’t along the lines of “write an essay for me about x in the style of y,” but rather “what could be a good example of x?” The system then suggests ideas or stories I hadn’t considered.

For example, this week, I’m working on chapter 5 of Duly Noted, which deals with organizing notes. I want to open each chapter with a story, and struggling to find one for this chapter. So I typed the following into ChatGTP:

Me: What is a good folk story or fairy tale about finding the right information among a large, confusing mass of stuff?

ChatGPT suggested Tolstoy’s The Three Questions and offered a summary. The description ended with the following sentence:

ChatGPT: … This story shows how sometimes the most valuable information can be found within ourselves, and that simplicity and clarity can often be more powerful than complex or conflicting advice from others.

That didn’t sound like what I was looking for, so my next prompt was more specific:

Me: Are there any such stories focused on finding information in a large set, such as a library?

ChatGPT offered two Borges stories: The Library of Babel and The Book of Sand — good choices but ones I can’t use since I’m opening chapter 4 with a Borges story. So I asked for similar stories not written by Borges, and it offered a few others, which, although in the general neighborhood, didn’t quite meet my needs. That’s when I realized a real-life story might be more compelling. So I switched gears:

Me: Are there examples of real-life stories along those lines? Something notable that happened that hinged on somebody losing something important among a large archive?

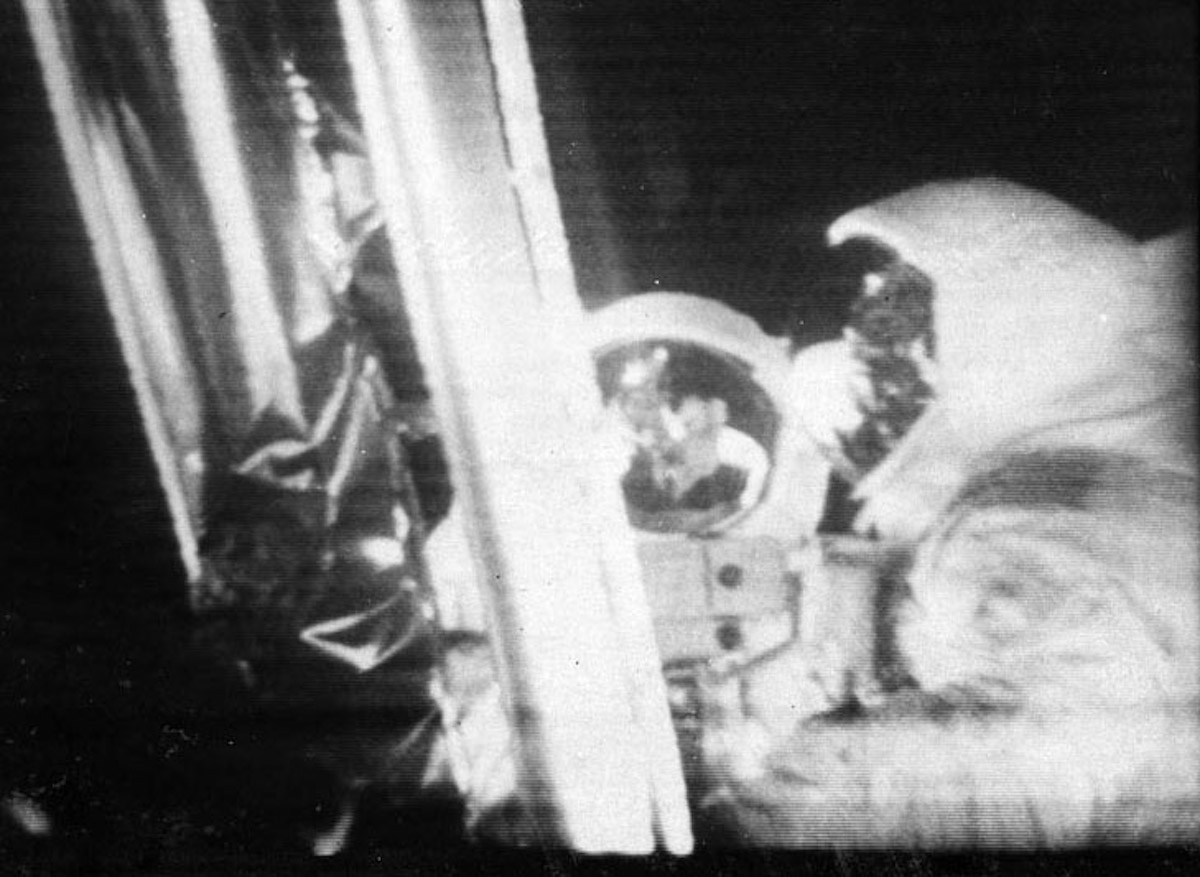

ChatGPT suggested the missing Watergate and Apollo 11 tapes and gave an overview of each. This answer ended with the following sentence, which piqued my interest:

ChatGPT: … These cases illustrate the importance of proper organization, preservation, and documentation in archives, and the potential consequences of losing valuable records or information.

This is close to what I want to illustrate in my chapter, so we were heading in the right direction. I was especially intrigued by the missing Apollo tapes since I’d never heard about this case. So I asked for follow-up suggestions:

Me: Where can I learn more about the lost Apollo 11 tapes?

To this, ChatGPT suggested four resources:

- A page on NASA’s website about the lost tapes

- Apollo 11: The Lost Tapes, a 2019 documentary from the Smithsonian Channel

- Chasing the Moon, a PBS documentary series about the space race

- The Apollo 11 Moon Landing: A Guide to the 50th Anniversary by Space.com

I got excited and tracked down these resources. That’s when I remembered that while ChatGPT can be an effective partner, it’s sometimes a drunk partner: as far as I can tell, two of these four resources don’t exist. But I did learn about the missing Apollo tapes, which led me to decide the story wasn’t quite right for my chapter.

The fact ChatGPT made up resources doesn’t negate its value for this use case. I wasn’t looking for the system to write the story for me: I just wanted to clarify my thinking. Even though it didn’t yield a specific example, this “conversation” led to an important insight: a real-life story will better serve my chapter. It also suggested where I might find such stories. (Government bureaucracy.)

Writing is thinking. And although I don’t expect to use systems like ChatGPT to write texts for me, composing the finished text isn’t all that writing entails. Developing ideas is an essential part of the process, and LLMs can serve in this role as intellectual — if sometimes drunk — partners.

That they sometimes lie doesn’t negate their usefulness since I have no intention of passing off their words directly. But the fact I can bounce off ideas clarifies my thinking and sometimes points me in new directions. This is valuable per se.

How about you? Are you using LLMs to augment or clarify your thinking? Please let me know, as I’m looking for stories for a chapter that deals with this subject. (See: you, too, can be a partner in the creative process.)