Point of view is worth eighty IQ points.

— Alan Kay

Sometimes we face situations that demand an immediate response. A few weeks ago, millions of Americans dealt with unexpected weather conditions that disrupted their ability to keep themselves and their families fed and warm. On February 20, the crew of United flight 328 had to deal with an engine that exploded in mid-air. (Fortunately — and through excellent piloting and engineering — the plane landed safely.) Such life-threatening situations call for skillful action now.

Most situations aren’t as urgent as landing a crippled plane or finding shelter in freezing temperatures. And yet, we often feel the stress of urgency in our day-to-day lives. Perhaps we’re on the hook for meeting this quarter’s KPIs, or we’re running late to take our child to her 10 am martial arts class, or we have a big presentation on Tuesday. Whatever the case, we’re under pressure to deliver now.

Focusing on near-term commitments is crucial if we aim to get things done. Meeting the company’s near-term goals contributes to its long-term success and helps our career. Following through with our commitments to our kids builds trust and sets positive examples for their future. That presentation may land the account that breaks us through. These ‘small’ things matter. We reach long-term goals one step at a time.

The problem comes when our perspective becomes fixated on the near-term. We may have good intentions, but when we’re called to allocate resources (i.e., time, effort, money), we always opt for present concerns. We aspire to lose weight by summer, but we’re hungry now. We want to build a world-class application, but we skip the research and modeling steps to get to ‘screens’ ASAP. We want our team to develop strategic influence, but we have a backlog to get through.

These aren’t either-or choices. We must eat if we plan to be alive by summer. Research and models are necessary but not sufficient; we must also aim for excellent screen-level interactions. We must deliver on our backlog commitments if we are to have any influence at all. The question isn’t what to do now, but how to balance near- and long-term commitments.

Ideally, near-term choices are in service of long-term goals. We must cultivate the ability to act now without losing sight of the long-term vision. This isn’t easy to do; we’re wired for the here-and-now. We’re drawn to the richest sources of nourishment in our environment. We discount future conditions, which we can’t experience through our senses. Because of this, long-term thinking requires practice — much like building muscle requires working out.

Fortunately, there are models, tools, and frameworks that can help us keep a long-term perspective as we act in the near-term. Here are three I find particularly helpful.

The Eisenhower Matrix

The Eisenhower Matrix is a prioritization framework attributed to U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower. Here’s how it works: draw a simple 2x2 matrix and label the X-axis ‘Urgency’ and the Y-axis ‘Priority.’ Now, sort your to-dos, appointments, commitments, etc. in one of the four quadrants:

- High priority, high urgency: do them ASAP.

- High priority, low urgency: you want to do these, but not necessarily right now. Schedule them. (And follow through!)

- Low priority, high urgency: these must be done, but not necessarily by you. Look for ways to delegate them.

- Low priority, low urgency: find a way to shed these.

The Eisenhower matrix assumes you’ve sorted out your priorities, so that’s the starting point. I haven’t found how to do this amid the daily bustle, so I periodically take time off to reexamine my priorities. I recommend you do the same.

(I first read about the Eisenhower matrix in Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. I haven’t revisited that book in many years, but it could be a good starting point for exploring this tool.)

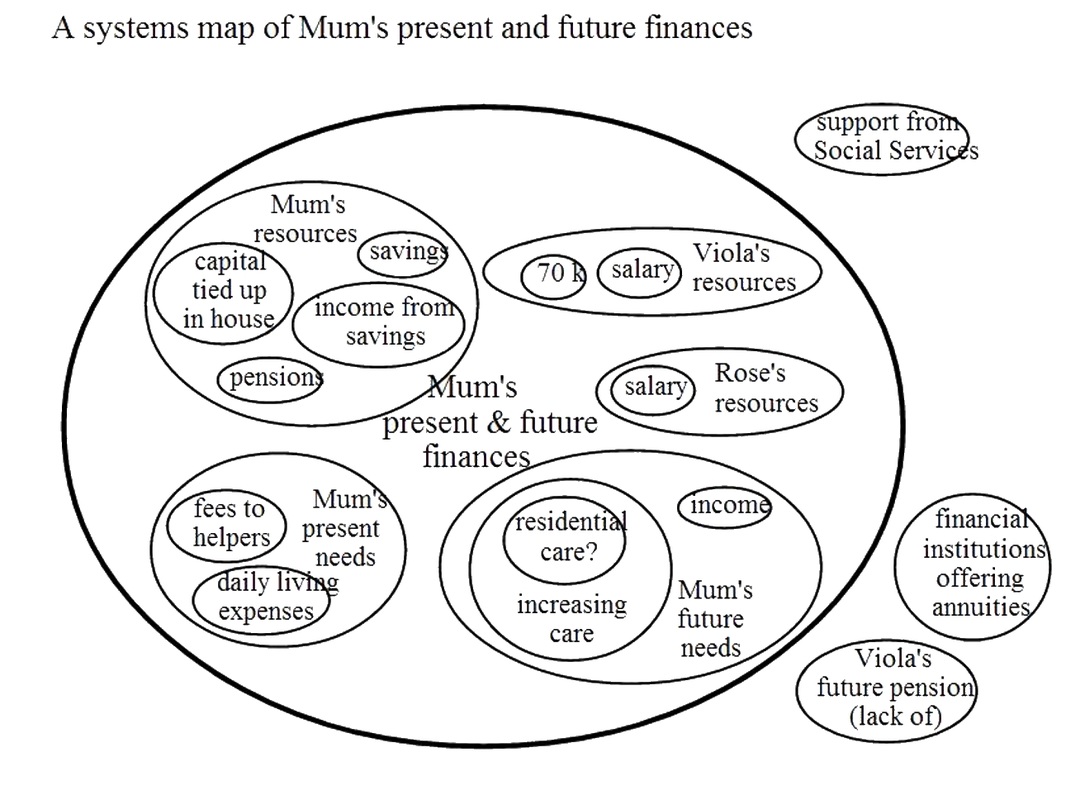

Systems diagrams

It’s difficult to understand the full complexity of a situation when we act in the moment. We’re attuned to things we can experience around us and tend to discount second-order effects. We can’t think about such things linearly. Taking in the bigger picture helps.

One way to do this is by mapping the components and actors that influence the situation and how they relate towards producing particular outcomes. Systems diagrams allow us to understand these relationships and identify key elements we may have missed.

Armson, 2011

Detailing such diagrams is beyond the scope of this post, but Rosalind Armson’s book Growing Wings on the Way offers a solid practical introduction. (Caveat: the Kindle edition has low-res diagrams. If I were to re-buy it, I’d get it on paper.)

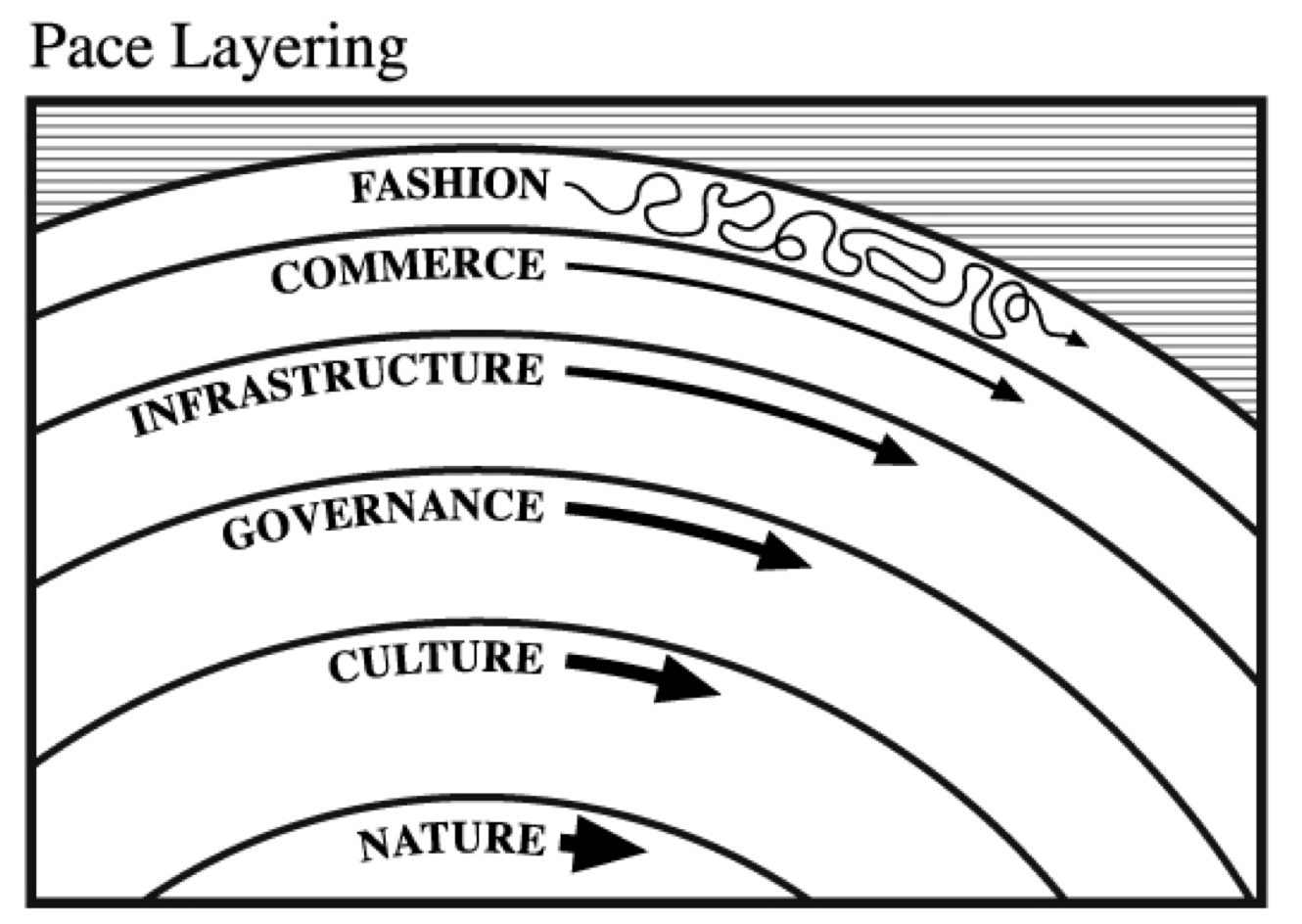

Pace layers

I’ve written before about pace layers, and with good reason: it’s one of the most valuable models for understanding the relationship between near-term actions and long-term impact.

The pace layers model explains how complex systems change over time. Such systems don’t change uniformly; instead, they’re composed of elements that vary in scale and rates of change. Grouping such elements into layers allows us to identify optimal strategies for enabling systems that evolve without compromising their structural integrity.

Brand, 1999

Faster-changing layers draw more of our attention, but slower-changing layers have greater power. Knowing what layers you’re dealing with and where your commitments lie helps you make more effective choices.

I can’t do justice to this subject in a short post, but Stewart Brand’s paper on the subject in the Journal of Design and Science is a good introduction.

Shifting between near- and long-term perspectives

Again, the idea isn’t to focus exclusively on the long-term. That’s a prescription for failure. What we want is to ensure our near-term actions support our long-term goals. This requires setting aside time once in a while to review our goals and priorities. Then we can use tools like those listed above during our day-to-day to ensure we’re aligned with our long-term aspirations.

Doing so helps us regain perspective: Not everything should be treated with the same degree of urgency. Some situations and systems are best served by adopting the attitude that they’re meant to endure. Conversely, some of our most complex and consequential challenges, such as climate change, require that we make near-term sacrifices for long-term payoffs that may not seem clear-and-present now. In this sense, the most urgent challenge we face may be how to overcome our misplaced sense of urgency.

I’d love to hear from you on this. How do you make space to keep the long-term in sight? Does your organization make it easy for you to do this, or do you always feel pressured to deliver on near-term objectives? What would help you make near-term choices that contribute to your (your family’s, your organization’s, your community’s) long-term well-being?

–

A version of this post first appeared in my newsletter. Subscribe to receive posts like this in your inbox every other Sunday.

Amazon links on this page are affiliate links. I get a small commission if you make a purchase after following these links.