Paul Graham posted a compelling essay about the perceived quality of first efforts. (In case you haven’t seen them, Graham’s essays are consistently insightful.)

Whenever you make something new, the first draft will be of doubtful quality and/or utility. In some cases, it may not be apparent to others — or even to yourself — that the project is leading anywhere. This can be scary, especially if you’re devoting considerable time and resources (whether yours or other people’s) to the endeavor.

How do you cast these fears aside so you can make progress? Graham explains:

The thing you’re trying to trick yourself into believing is in fact the truth. A lame-looking early version of an ambitious project truly is more valuable than it seems. So the ultimate solution may be to teach yourself that.

One way to do it is to study the histories of people who’ve done great work. What were they thinking early on? What was the very first thing they did? It can sometimes be hard to get an accurate answer to this question, because people are often embarrassed by their earliest work and make little effort to publish it. (They too misjudge it.) But when you can get an accurate picture of the first steps someone made on the path to some great work, they’re often pretty feeble.[8]

Perhaps if you study enough such cases, you can teach yourself to be a better judge of early work. Then you’ll be immune both to other people’s skepticism and your own fear of making something lame. You’ll see early work for what it is.

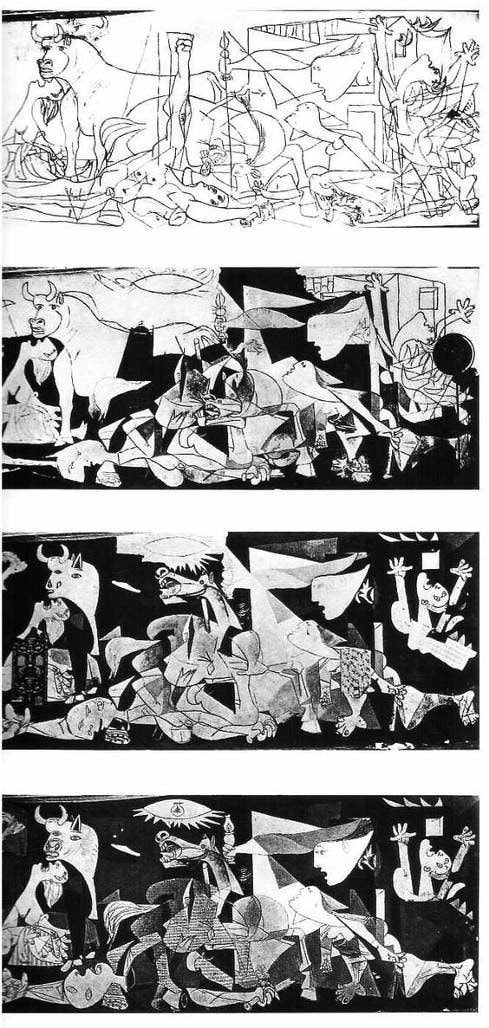

The form these cases take varies depending on the field you’re examining. We know a lot about the early phases and evolution of some paintings. For example, Dora Maar photographed Guernica throughout its various stages.

Photos of Guernica’s late stages. Source: Journal of Art in Society

Other fields are less documented, perhaps because people are already busy enough making the thing. Also, if you’re unsure the endeavor will be worth it, what’s the worth of documenting its evolution?

Maar photographed Guernica when Picasso was already an established artist. Documenting the process would be valuable even if the painting went nowhere. It’s harder to make the case for documenting the process of a “crazy” project by an “unknown” creator.

Still, documenting creative endeavors seems like an underserved area of literature. It would be wonderful to explore the (honest!) evolution of all sorts of things, from their first tottering steps to their current state. As suggested in the essay’s footnotes, doing so for even “trivial” projects seems more feasible now that we have pervasive means for capturing information.