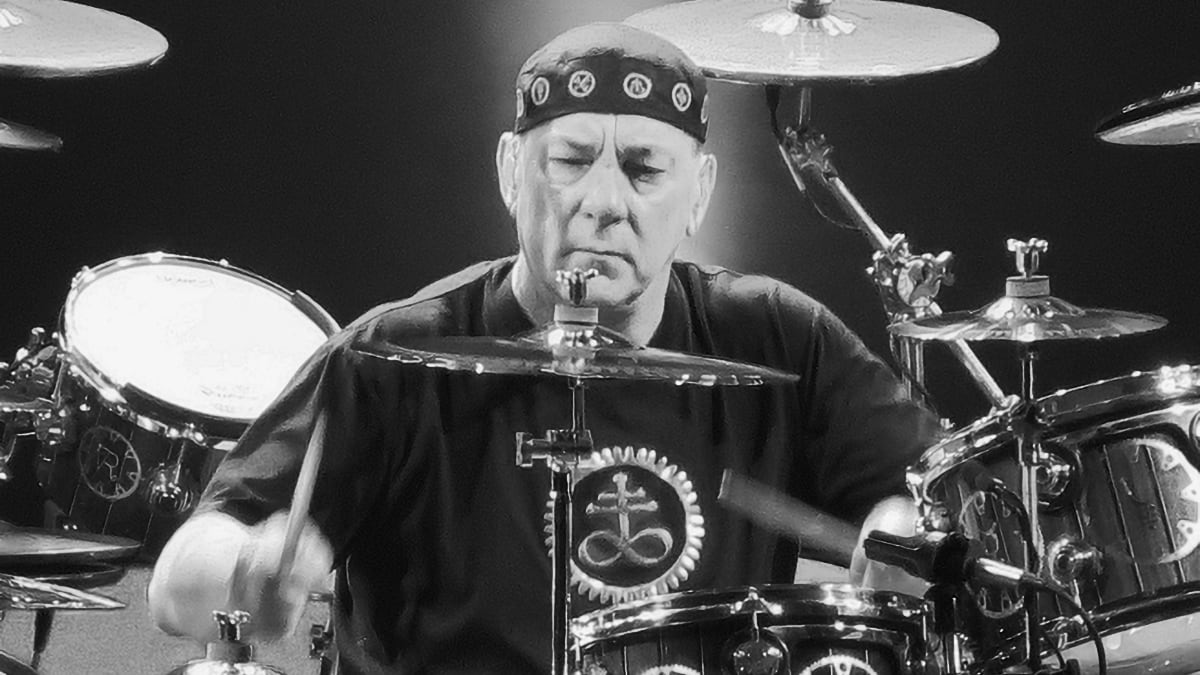

Yesterday, as I was winding down from a busy week, I learned of the death of someone who influenced me greatly: Rush drummer and lyricist Neil Peart. As with so many other nerds of my vintage, Rush’s songs — and especially their lyrics, most of which were written by Mr. Peart — are key to the soundscape of my formative years. I never met Mr. Peart, although I did have the privilege of seeing him play live. Nevertheless, I consider him a model of integrity and mastery, someone to emulate.

It’s clichéd to highlight the geeky teen appeal of Rush’s (early) sci-fi themes. Instead, what drew me to their songs was their advocacy of self-agency. For someone brought up as Catholic, this stance — exemplified by the song Freewill — was shocking and refreshing:

There are those who think

That life has nothing left to chance

A host of holy horrors

To direct our aimless danceA planet of playthings

We dance on the strings

Of powers we cannot perceive

The stars aren’t aligned

Or the gods are maligned

Blame is better to give than receiveYou can choose a ready guide in some celestial voice

If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice

You can choose from phantom fears and kindness that can kill

I will choose a path that’s clear, I will choose freewill

Rush’s songs pointed me towards that clearer path a long time ago. (As a result, I often find myself at odds with the current zeitgeist, which encourages us to look outside ourselves for the source of our problems.) But it’s one thing to talk about relying on and developing one’s self, and another to behave in ways that support that belief. Growing and deepening our craft is hard work. As we gain some degree of ability and renown, shortcuts beckon. We’re tempted to slack off “just this once;” after all, we’ve already “put in our time.” We feel entitled to ride our reputations. Before long, only the talk remains.

I expect it’s especially challenging to lead a life of discipline and commitment to self and craft in a domain as dissolute as rock ’n roll, where the norm is for brilliant talents to be consumed by their context and newfound powers. (Keith Moon and John Bonham — two drummers revered by Mr. Peart — were killed by their excesses early on.) In contrast, Neil Peart’s abilities evolved and deepened over a long career. He suffered significant setbacks — most notably, the deaths of his wife and daughter within a year of each other — that could’ve derailed his life. And yet he found the strength to grow from his experiences. Intriguingly, the ensuing work included some of Rush’s most moving and heaviest songs.

I sense that Mr. Peart was driven more by the will to master his two percussive instruments — the drums and the typewriter — than by the world’s acclamation for doing so. In the second half of his career, when he was already acknowledged as one of the best drummers in the world, he had the humility to engage teachers so he could re-learn his craft from different angles. But his career isn’t only a model of commitment to technical mastery: there’s also the matter of learning to collaborate effectively with other brilliant people. Where many bands are destroyed by inflamed rock star egos, Rush seems to have grown stronger, closer, and more creative over four decades. Their final studio album, Clockwork Angels, had the band evolving in new directions and producing some of their strongest material in years.

In a world where appearances seem to matter more every day, it’s essential to acknowledge, highlight, and celebrate real mastery. Neil Peart was its embodiment.

Living in the limelight

The universal dream

For those who wish to seem

Those who wish to be

Must put aside the alienation

Get on with the fascination

The real relation

The underlying theme— Neil Peart, 1952-2020