The architecture of information:

A month ago, Microsoft introduced several new computers to its Surface line. While some of the new devices were incremental advances, one of them — the Surface Pro X — is a modern reinterpretation of the product line. It’s physically sleeker than previous Surface tablets. It features a new stylus that can be stored in the tablet’s keyboard. And, most importantly, it uses a new ARM processor architecture, like the one used by smartphones.

This last point is worth noting. One of the advantages of using Windows tablets over iPads is that the latter lack the breadth of software available for Windows. But in many cases, software “for Windows” really means “for Windows on traditional Intel processors.” Some of the apps that run “on Windows” are incompatible with the new ARM processors in the Surface Pro X tablets, even though they, too, run Windows. In other words, it’s complicated.

In his review of the device for The Verge, Dieter Bohn calls out app compatibility issues as one of the downsides of the new device. The review is worth reading for details into the complexities of this processor transition. The challenges are nuanced: some apps will run slowly, others won’t run at all. One issue stood out to me:

Everybody has one or two apps they absolutely need to do their job. With the Surface Pro X, there’s no real way to know if it will run well (or at all) without doing a ton of research ahead of time. Dropbox, for example, only works as an insular “S-Mode” app and can’t sync your files automatically.

Heck, even Microsoft’s own app store doesn’t properly filter out incompatible apps when you visit it from this computer. You can (and I did!) buy apps in the Microsoft Store and only find out after the fact that they’re incompatible. Microsoft promises that it will fix this issue, but for now consumers are left to their own devices to figure it out.

This strikes me as an excellent example of an information architecture needing to change to meet the needs of its ecosystem. Under most circumstances, target processor architecture isn’t a metadata field you’d want to surface (pardon the pun) to users of a consumer app store. Most people won’t care about such esoteric details most of the time. But they will care if you introduce a product that depends on it.

Customers will be especially frustrated if they pick the product based on the brand’s promise of greater app breadth. This is a strategic issue since the lack of app availability erodes an important differentiator of the product line. These compatibility issues make the new product a tough sell, and muddies the overall brand message. But it’s tougher still if customers discover these issues by trial and error. (Note: I’m not a Windows user, so I haven’t used the Microsoft Store recently. I’m going here by what I’m reading in the review.)

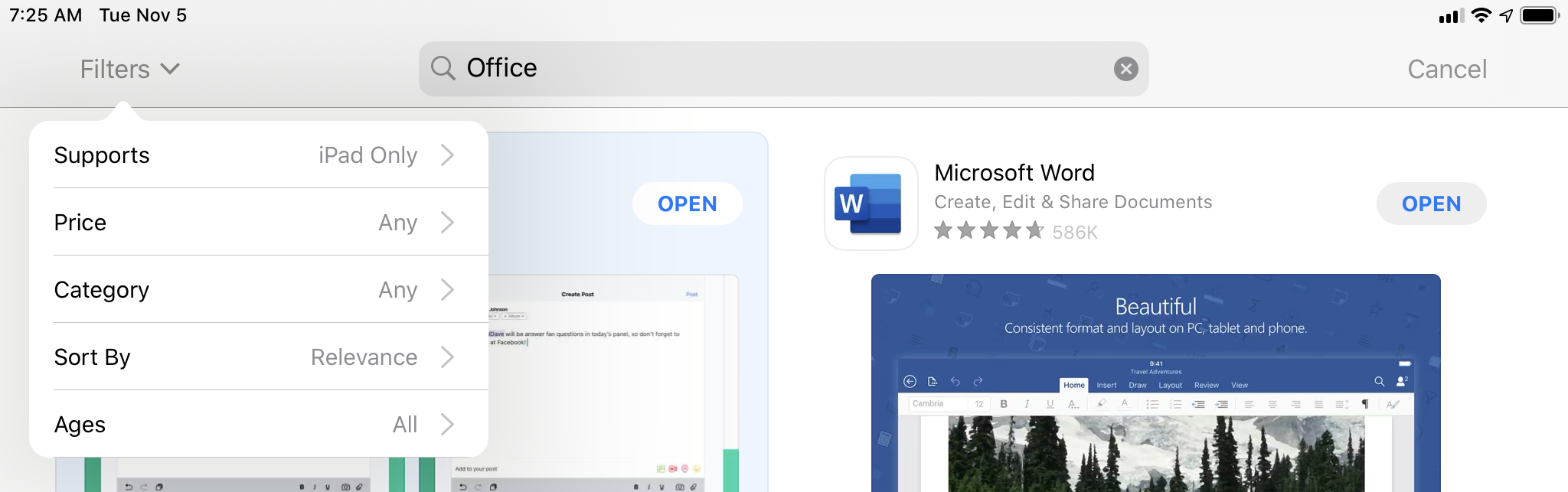

How could the app store better support customers through the transition to the new architecture? As Mr. Bohn points out, one way is to allow them to filter apps based on the device. (“Show only compatible apps.”) Apple does something similar with the App Store in iOS/iPad OS:

Filters in the iPadOS App Store.

But such a filter is subtle and reactive; users must know that it’s there, and why the distinctions it offers matter to them. Given how central app breadth is to the Surface brand promise, I’d try to give the issue more visibility, perhaps even look for a way of turning it into an asset. (Featured section: “Optimized for Surface Pro X.”) The point is: once processor architecture compatibility becomes a distinction that users must care about, it’s incumbent on the information environment to make that distinction clear, and allow customers to make good decisions based upon it.

IA isn’t just about making it possible for people to navigate an information environment; it’s also about educating them about their choices, and why they matter. When those choices have strategic import — as it does now for the Surface app ecosystem — the environment should change to raise their visibility accordingly.