Folks who know me well know I’m a fan of the Disney theme parks. I consider Disneyland among the most successful places designed in the Twentieth Century. I’ve written about some of the reasons why (and about what UX designers can learn from the park) in a post titled 3 Placemaking Lessons From the Magic Kingdom; I recommend you read that before proceeding so you can get a sense of the lens through which I see these experiences.

I visited Shanghai last month for work. While there, I had the opportunity to visit the newest Disney theme park, which is in Pudong. In this post, I’ll share some of my impressions of Shanghai Disneyland and contrast it with the other Disney “castle” parks. (I’ve visited the parks in Anaheim, Orlando, and Paris.) There are many similarities between these Disneylands, but also significant differences.

Let’s start with the similarities. The most obvious is the structural layout of Shanghai Disneyland. There’s a castle in the center of the park that serves as a focal point. (A “wienie,” to use Walt Disney’s term.) The castle — Shanghai’s is the largest of all of Disney’s parks — helps guests orient themselves and navigate the environment.

Enchanted Storybook Castle in the center of Shanghai Disneyland.

The castle is surrounded by “lands” that are arranged radially around it. All lands contain attractions, restaurants, and retail and services facilities. Attractions range from passive (yet consistently pleasing and well-designed) experiences to technologically advanced thrill rides. Lands, attractions, restaurants, and shops are themed to Disney movies and characters. You enter the park through one of these lands, which is arranged as a promenade through a retail corridor.

As with the other Disney resorts, the park itself is but one part of a larger complex that includes hotels, retail and dining facilities, transportation, etc. While in the resort, you’re immersed in Disney’s world; you’re surrounded by visual and audio cues from Disney movies. You’re also treated to a consistently high standard of customer service, a hallmark of Disney hospitality.

That’s where similarities end. Walt Disney Co. CEO Bob Iger has stated that Shanghai Disneyland aims to be “authentically Disney and distinctly Chinese.” Based on my short visit, I sense that the park’s designers succeeded in achieving this goal.

No burgers here! Authentically Disney, distinctly Chinese.

To someone familiar with the stateside Disney parks, being in Shanghai Disneyland feels like stepping into an alternate universe. You’ll recognize some things. For example, Dumbo the Flying Elephant is similar to Dumbo rides around the world. But others are either completely new or from-the-ground-up re-interpretations of previous Disney experiences. Given our work responsibilities, my group and I were only able to devote half a day to Disneyland, so we focused on experiencing two of the new/improved attractions: Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for the Sunken Treasure and TRON Lightcycle Power Run.

The latter is a thrilling rollercoaster themed to the TRON movies. The ride is housed in one of the most beautiful buildings in any Disney park; there’s nothing like it in any other Disneyland. (For now — a clone of this ride is being built in Orlando.)

The pirates ride is a re-imagining of the classic Disneyland experience. You still cruise in a boat through a world inhabited by animatronic pirates and their victims. However, the ride uses spectacular technology to tell a new story featuring characters and scenes from the Pirates of the Caribbean movies starring Johny Depp.

These movies were based, of course, on the Disneyland pirates ride. So the Shanghai ride is a curious third-generation artifact: a ride based on a movie based on an older ride. For all its advanced technology, Battle for the Sunken Treasure is rife with callbacks to both the original Disneyland pirates ride and the movies that are based upon it. (All in Mandarin, of course.) I’m highlighting this because it’s representative of the Shanghai Disneyland experience as a whole: While the original Disneyland was designed so guests could experience the worlds of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy (as conceived by mid-1950s Californians), Shanghai Disneyland is designed for guests to experience the worlds of Disney.

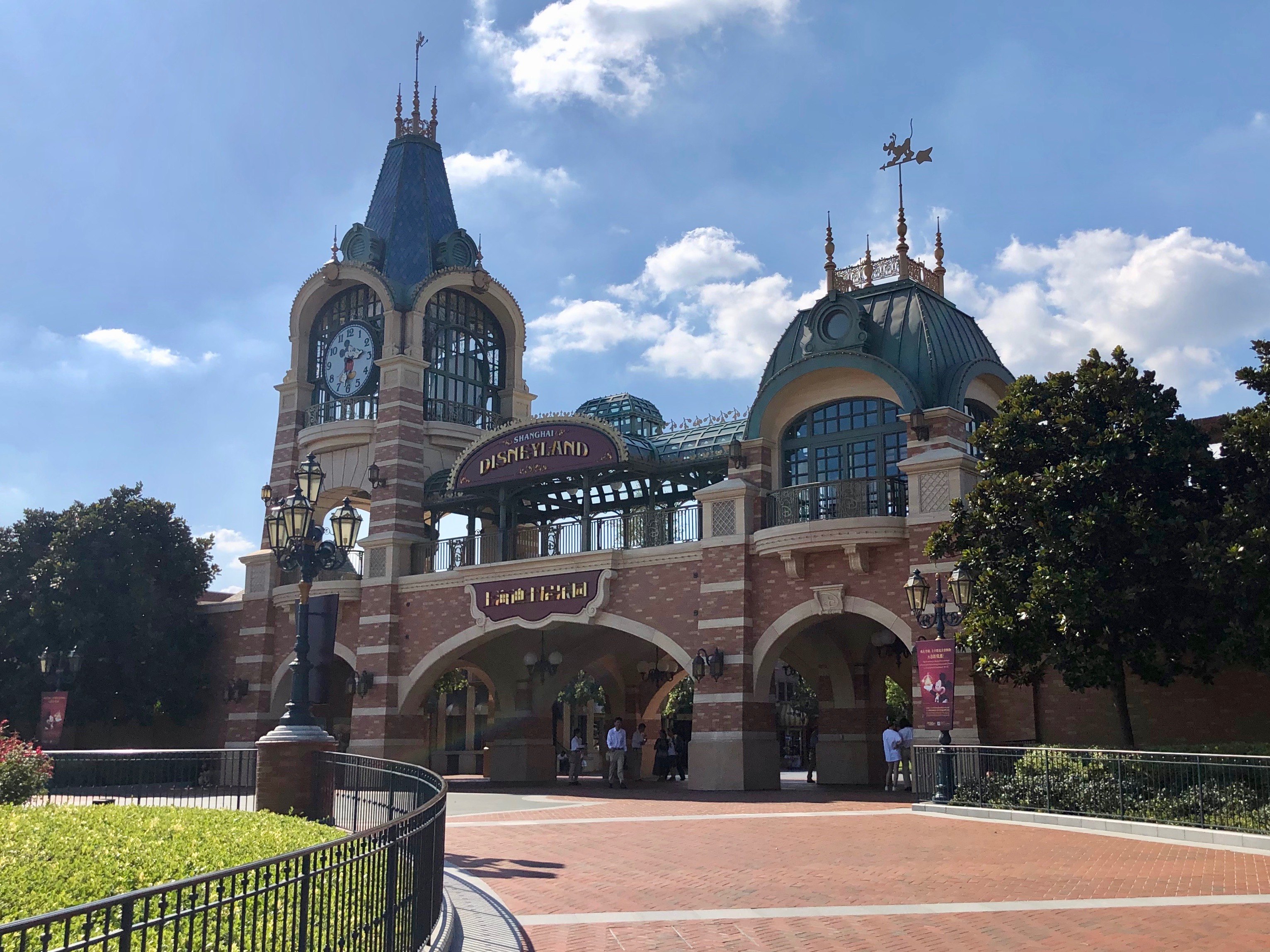

In other words, the Shanghai park is an ouroboros: Self-reference is everywhere. For example, instead of the original’s Main Street U.S.A., which was designed to evoke typical small town America at the turn of the Twentieth Century, Shanghai Disneyland features Mickey Avenue, a line of fantastic buildings that evoke Disney’s characters’ homes. Another small detail serves to illustrate: The face of the clock atop the faux train station (there’s no railroad encircling the park as with most other Disneylands) isn’t a replica of an old-time clock. Instead, it evokes the face of the classic Ingersoll Mickey Mouse wristwatch, something you’d be unlikely to see in a clocktower in the “real” world.

This building takes the place of the train stations in other Disneyland parks. Notice the Mickey Mouse clock on the tower.

I knew about these design decisions before visiting the park and was expecting to be put off. The reflection of reality through Disney’s lens — reduced in scale, stereotyped, fantasized — is one of the aspects I most appreciate in Disneyland parks. But self-reference makes a lot of sense in Shanghai, a city buzzing with novelty. Most guests in this park don’t have cultural memories of midwestern American small towns or European fairy tales. Instead, Shanghai Disneyland taps nostalgia for Disney characters and stories, especially those from the late 1980s and early 1990s, when China’s boom began.

I’m not a member of the target demographic, so this park’s approach didn’t resonate as much with me. I still enjoyed the place, but not as much as I would have if this were my first Disneyland experience. This park doesn’t have the depth or history of the others; its focus is squarely on creating a setting for people to experience the company’s intellectual property. It’s masterful in achieving its own ends — but those ends are at odds with what I enjoy most about Disney parks.

That said, I saw one detail that elevated the experience for me: a painting on the wall in a jewelry shop inside the castle. The image depicts the Disney princesses, ostensibly the characters the castle is celebrating. However, the princesses occupy only half of the painting. The other half focuses on another woman: A Chinese artisan at work, making the very products that are for sale in the shop:

Painting inside Enchanted Storybook Castle at Shanghai Disneyland.

This painting beautifully captures the spirit of Shanghai Disneyland: it’s both a celebration of Disney’s intellectual property and of a people who’ve raised themselves to middle class through hard work (and, implicitly, through political, economic, and social changes that have allowed them to enjoy the fruits of that work) to the point where they can afford a Disneyland that is distinctly their own.