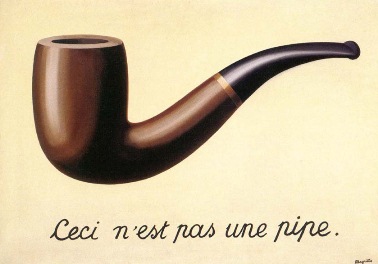

Ninety years ago, René Magritte painted a pipe. I’m sure you’ve seen the work; it’s among his most famous. Written under the rendering of the object are the words Ceci n’est pas une pipe — “This is not a pipe.” Huh? Well, it isn’t; it’s a representation of a pipe. Clever stuff.

The painting is called La Trahison des images — “The Treachery of Images.” Treachery means to deceive; to betray our trust. The painting tricks us by simulating a familiar object. Aided by the charming image, our mind conceives the pipe. We recall experiences with the real thing — its size, weight, texture, the smell of tobacco, etc. Suddenly we’re faced with a conundrum. Is this a pipe or not? At one level it is, but at another it isn’t.

The Treachery of Images requires that we make a conceptual distinction between the representation of an object and the object itself. While it’s not a nuanced distinction – as far as I know, nobody has tried to smoke Magritte’s painting – it’s important since it highlights the challenges inherent in using symbols to represent reality.

The closer these symbols are to the thing they’re representing, the more compelling the simulation. Compared to many of Magritte’s contemporaries, his style is relatively faithful to the “real world.” That said, it’s not what we call photo-realistic. (That is, an almost perfect two-dimensional representation of the real thing. Or rather, a perfectly rendered representation of a photograph of the real thing.)

Magritte’s pipe is close enough. I doubt the painting would be more effective if it featured a “perfect” representation; its “painting-ness” is an important part of what makes it effective. The work’s aim isn’t to trick us into thinking that we’re looking at a pipe, but to spark a conversation about the difference between an object and its symbolic representation.

The distance between us and the simulation is enforced by the medium in which we experience it. You’re unlikely to be truly misled while standing in a museum in front of the physical canvas. That changes, of course, if you’re experiencing the painting in an information environment such as the website where you’re reading these words. Here, everything collapses onto the same level.

There’s a photo of Magritte’s painting at the beginning of this post. Did you confuse it with the painting itself? I’m willing to bet that at one level you did. This little betrayal serves a noble purpose; I wanted you to be clear on which painting I was discussing. I also assumed that you’d know that that representation of the representation wasn’t the “real” one. (There was no World Wide Web ninety years ago.) No harm meant.

That said, as we move more of our activities to information environments, it becomes harder for us to make these distinctions. We get used to experiencing more things in these two-dimensional symbolic domains. Not just art, but also shopping, learning, politics, health, taxes, literature, mating, etc. Significant swaths of human experience collapsed to images and symbols.

Some, like my citing of The Treachery of Images are relatively innocent. Others are actually and intentionally treacherous. As in: designed to deceive. The rise of these deceptions is inevitable; the medium makes them easy to accept and disseminate, and simulation technologies keep getting better. That’s why you hear in the news about increasing concern for deepfakes.

Recently, someone commercialized an application that strips women of their clothes. Well, not really — it strips photographs of women of their clothes. That makes it only slightly less pernicious; such capabilities can do very real harm. The app has since been pulled from the market, but I’m confident that won’t be the last we see of this type of treachery.

It’s easy to point to that case as an obvious misuse of technology. Others will be harder. Consider “FaceTime Attention Correction,” a new capability coming in iOS 13. Per The Verge, this seemingly innocent feature corrects a long-standing issue with video calls:

Normally, video calls tend to make it look like both participants are peering off to one side or the other, since they’re looking at the person on their display, rather than directly into the front-facing camera. However, the new “FaceTime Attention Correction” feature appears to use some kind of image manipulation to correct this, and results in realistic-looking fake eye contact between the FaceTime users.

What this seems to be doing is re-rendering parts of your face on-the-fly while you’re on a video call so the person on the other side is tricked into thinking you’re looking directly at them.

While this sounds potentially useful, and the technology behind it is clever and cool, I’m torn. Eye contact is an essential cue in human communication. We get important information from our interlocutor’s eyes. (That’s why we say the eyes are the “windows to the soul.”) While meeting remotely using video is nowhere near as rich as meeting in person, we communicate better using video than when using voice only. Do we really want to mess around with something as essential as the representation of our gaze?

In some ways, “Attention Correction” strikes me as more problematic than other examples of deep fakery. We can easily point to stripping clothes off photographs, changing the cadence of politician’s speeches in videos, or simulating an individual’s speech patterns and tone as either obviously wrong or (in the latter case) at least ethically suspect. Our repulsion makes them easier to regulate or shame off the market. It’s much harder to say that altering our gaze in real-time isn’t ethical. What’s the harm?

Well, for one, it messes around with one of our most fundamental communication channels, as I said above. It also normalizes the technologies of deception; it puts us on a slippery slope. First the gaze, then… What? A haircut? Clothing? Secondary sex characteristics? Given realistic avatars, perhaps eventually we can skip meetings altogether.

Some may relish the thought, but not me. I’d like more human interactions in information environments. Currently, when I look at the smiling face inside the small glass rectangle, I think I’m looking at a person. Of course, it’s not a person. But there’s no time (or desire) during the interaction to snap myself out of the illusion. That’s okay. I trust that there’s a person on the other end, and that I’m looking at a reasonably trustworthy representation. But for how much longer?