One of the most challenging things about creating a prototype is determining what its level of fidelity should be. By “fidelity” I mean how closely it approximates a real artifact that end users would interact with. Lower fidelity prototypes are more abstract; they require greater leaps of imagination from people who interact with them. On the other hand, higher fidelity prototypes fill in the details, leaving little to the imagination. You’d expect the latter to be the best option, but that’s not always the case.

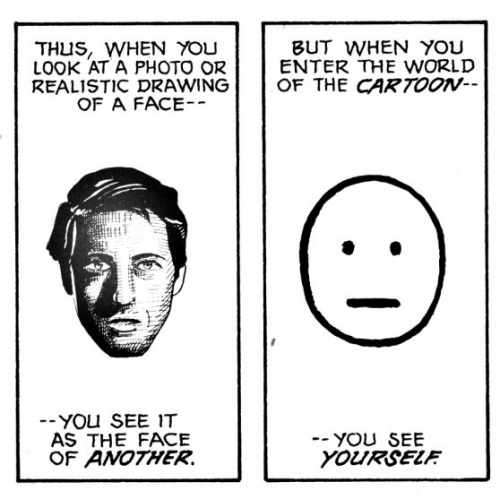

In his classic book Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud discusses the ability of the comics medium to harness the power of abstraction:

Something like this happens when you interact with a low fidelity prototype. Your mind starts filling in the details; you make the thing your own. This can be very valuable, especially in the early stages of a project when the design team only has a high-level understanding of their objectives. At this stage, the team is working in ambiguous conditions; a low fidelity prototype can help the team reduce the ambiguity. On the flip side, a high fidelity prototype is more likely to elicit feedback on the formal aspects of the experience: what it looks and feels like.

Determining the right level of fidelity for a prototype requires thinking about the objectives it’s expected to serve. With a lower fidelity prototype, you’re more likely to focus on the “big idea,” since there are few details to distract your attention. The challenge is that lower fidelity artifacts are more abstract, and many people have trouble with abstraction. A prototype can be of such low fidelity that people have a difficult time even imagining it as a thing in the world, at which point its usefulness is limited. You want a level of fidelity that’s appropriate for the stage of the process you’re in, and the sort of feedback that would help you at this stage.

Amazon links on this page are affiliate links. I get a small commission if you make a purchase after following these links.