A transcript of a presentation I delivered (remotely) at the AIDA4 conference in Krakow, Poland.

Many people come to information architecture from the information sciences. That’s not my case. I came to this field from architecture. Architecture is an interesting design discipline in that it’s intertwined with technology. The shapes of our physical environments — the contexts where our experiences play out — are deeply influenced by the capabilities of our technologies, and that has been the case for a long time.

Photo by FlorentMartin_ via Flickr

For over 4,500 years, the Great Pyramid of Cheops was the tallest building in the world. But the people who built it wouldn’t dream of living or even going to the top of this thing. As you know, it was built as a funerary monument, not as a place to hang out. For much of our history, people lived in much shorter places, like the ones in the foreground of this picture. We built horizontally, not vertically. That is no longer the case.

Photo by jean-marc via Flickr

Ancient Egyptians couldn’t have conceived of people living in tall buildings like the ones in New York City. Why would you think that is? For one thing, it’s really inconvenient to live so high up in the absence of elevators. You wouldn’t want to live in a twenty-fifth floor apartment if you had to walk up stairs while carrying your groceries.

The elevator changed the shape of our world. It was a deeply transformational technology. Of course, it didn’t happen on its own. There are other technologies that enabled and complemented elevators, such as reinforced concrete and electricity. There’s a whole constellation of technologies that led to the shape of tall cities like New York.

I will put forth to you that generative AI is one of these deeply transformative technologies, like the elevator. I’m convinced that it’s the most important new information technology since the World Wide Web and it will render our current world unrecognizable, much as New York City would have blown the minds of ancient Egyptians.

Don’t Believe the Hype

Now, I know that this sounds a bit grandiose and I’m kind of playing into the current narrative, which feeds on hype about these things. The hype is driven by a misunderstanding of what these things are and how they work. And it’s also driven, in no small part, by marketing.

In particular, I’m convinced that the phrase artificial intelligence is a misnomer that doesn’t do justice to what these things are. It’s both creating unrealistic expectations and underselling what these things can do. The misunderstanding is also driven by how ‘AIs’ have been packaged: in chat-based user interfaces that anthropomorphize them.

ChatGPT: the standard interface for ‘AI’

Companies are also rushing to implement AI-powered solutions, driven not by what is best for users but out of a fear of missing out on the latest technology or paranoia about being left behind competitively. Or maybe it’s just greed. Whatever the case, organizations want to dominate a market and they see AI as a way in. But the result is a lot of implementations that are, in my opinion, suboptimal.

Meme via Facebook

The emerging cliché is to simply graft a chatbot onto an existing system. While that may be appropriate in some cases, it definitely isn’t for all of them. Another problem is that vendors are primarily focused on automation use cases.

LLMs are controversial because the tech is best at augmentation but is being sold by lots of vendors as automation.

— Dare Obasanjo🐀 (@Carnage4Life) June 10, 2024

The technology holds a lot of potential there, but it’s by no means the only approach. One way to think about this is that we can either design AI-powered experiences or we can use AI to design better experiences. They’re not mutually exclusive, but there’s an important distinction emerging.

A Spectrum of Possible Uses for AI

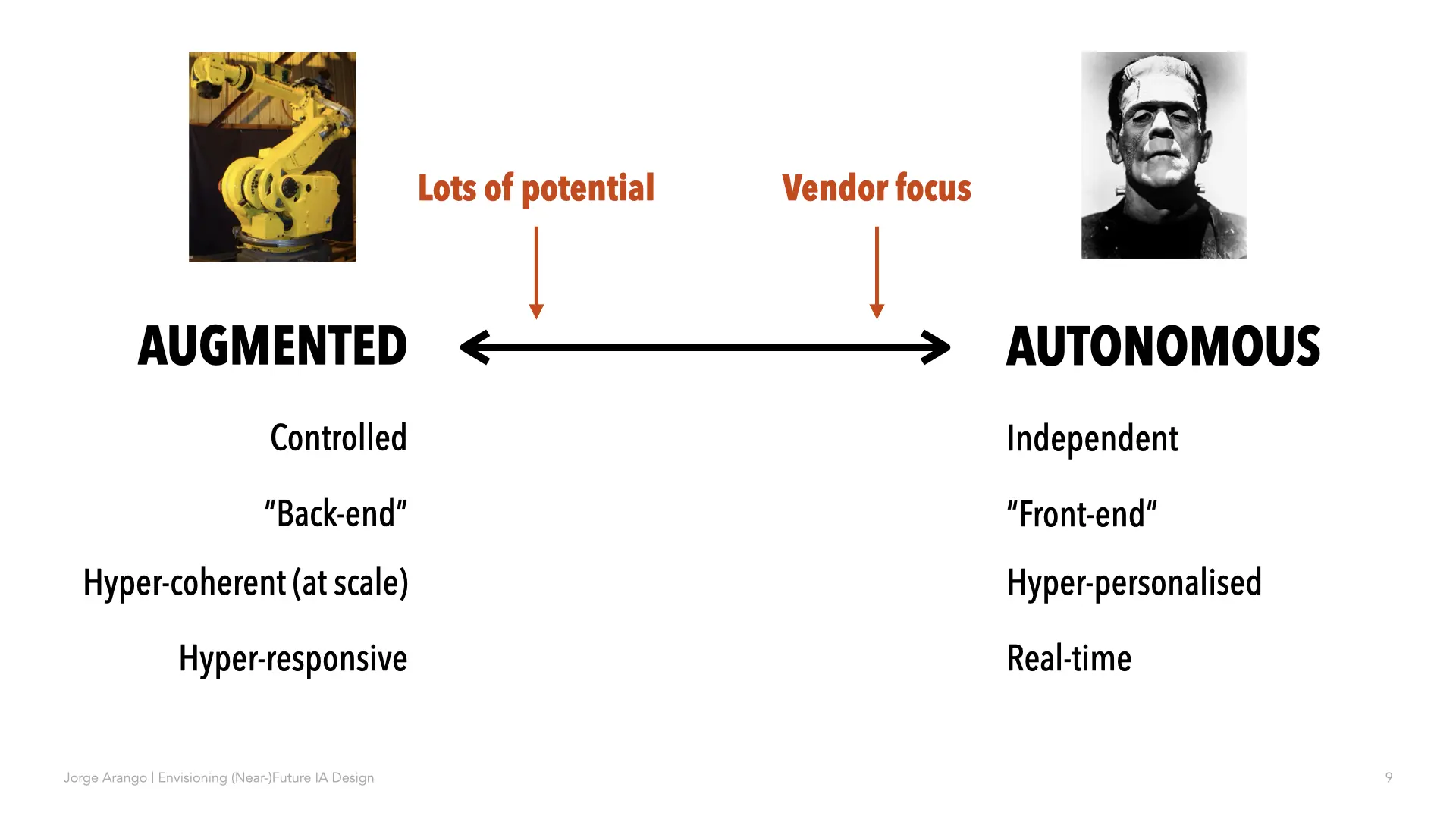

Consider a spectrum of ways to use AI to design digital experiences. On one end, there are systems that use AI to deliver the final experience independently of human intervention. These systems are best suited to generating hyper-personalized experiences for individual users’ needs. They must be composed dynamically in real time.

On the other end of the spectrum, AI is used to augment the work of the people who design digital experiences. These experiences can be more tightly controlled by smaller teams working at much larger scale with much greater coherence and scope.

Robot arm via Fanuc Robot 2 via Flickr , Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster © Universal Pictures via Wikipedia

One outcome of keeping humans in the loop is fewer hallucinations. The work can also be done faster and better. As a result, smaller design teams can be more responsive to changing market conditions, and do it more safely, by augmenting traditional design approaches rather than by replacing human designers altogether.

Alas, as Mr. Obasanjo suggests, most vendors are currently pushing the automation angle. I think that’s partly because it’s good marketing. But also, it seems to fulfill long-standing human fantasies about creating artificial life. But that end of the spectrum is fraught with problems. There’s a storied literature about the risks of creating artificial life.

And even though autonomy holds a lot of potential, the technology is still far from delivering it. And there are a lot of gains to be had if we think of the use of these tools primarily on the augmentation side of the spectrum. In other words, as ways to work faster, more cheaply, and at greater scale — not to make decisions instead of humans but to help humans make better decisions more quickly.

A Useful Analogy

It’s important to take a step back from the hype and take a fresh look at what these things are and are not. The tools currently packaged as AI are not sentient. They don’t have a theory of mind. They are not conscious. They don’t have any of the magical powers that people currently ascribe to them.

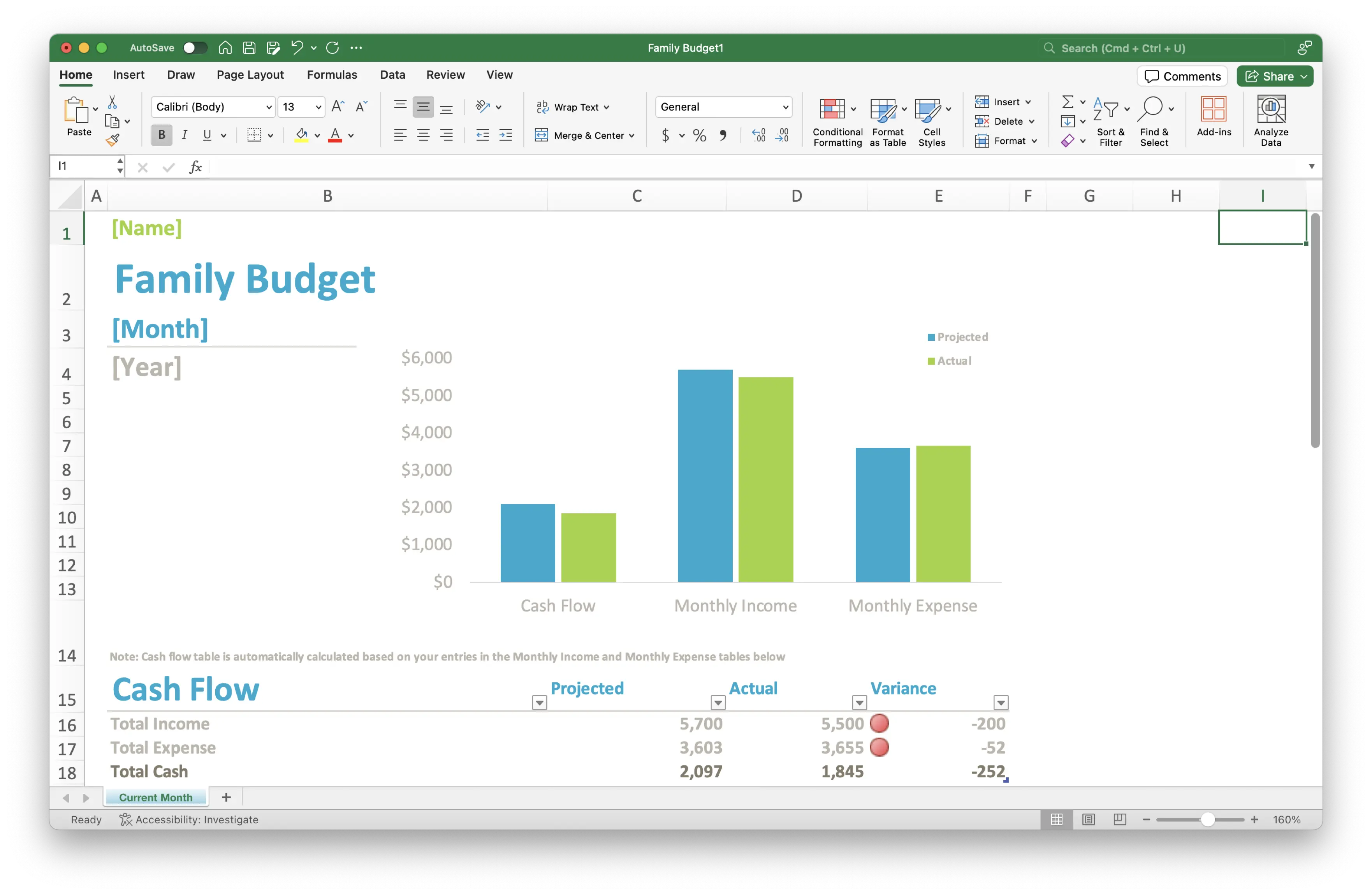

That doesn’t mean they’re not useful. They still give us incredible capabilities to work with information in ways that we have never been able to before. But it’s going to require thinking differently about what they are and how we work with them. It’s going to require different metaphors. A useful one I came across recently was to think of them as analogous to spreadsheets.

Consider what spreadsheets did for working with numbers: they made it possible for everyday people to tap into the power of computers to do very powerful things. Spreadsheets allow you to run a budget, to forecast the impact of decisions, to do modeling. They allow you to store structured data. These capabilities are available to you without having to know programming.

In some ways, language models are like spreadsheets. But rather than allowing you to process numbers, they allow you to process and compute other semantic symbols. Think of them as opening to computation the entirety of humanity’s symbolic production: every concept that’s ever been expressed or that can ever be expressed is now fodder for computation.

That is an incredible new power LLMs give us that doesn’t require that we think of them as sentient entities. Even if we just get the power to transform symbols at scale, it’s an amazing new capability. Let me give you a small example of what it’s like for information architects to work at this augmentation end of the spectrum.

An Example: Re-tagging My Site

I recently used GPT-4 to help with a mundane, tedious information architecture task. It centered on a challenge with my personal website, jarango.com. I’ve posted close to 1,200 blog posts on this site since the early 2000s. Alas, older content was not very discoverable. It’s a common issue with blogs: the attention falls on the newer stuff.

I planned to solve this by implementing a “see also” functionality on the site. But to implement the feature, all posts on the site needed to have consistent metadata. In particular, each post had to be tagged with a minimum of three terms from a common taxonomy.

The problem was that my site, as so many long-standing blogs, did not have consistent tags; I had to re-tag everything. This was a very tedious operation: I estimated that if I did it manually, it would take around ten hours of mind-numbing work.

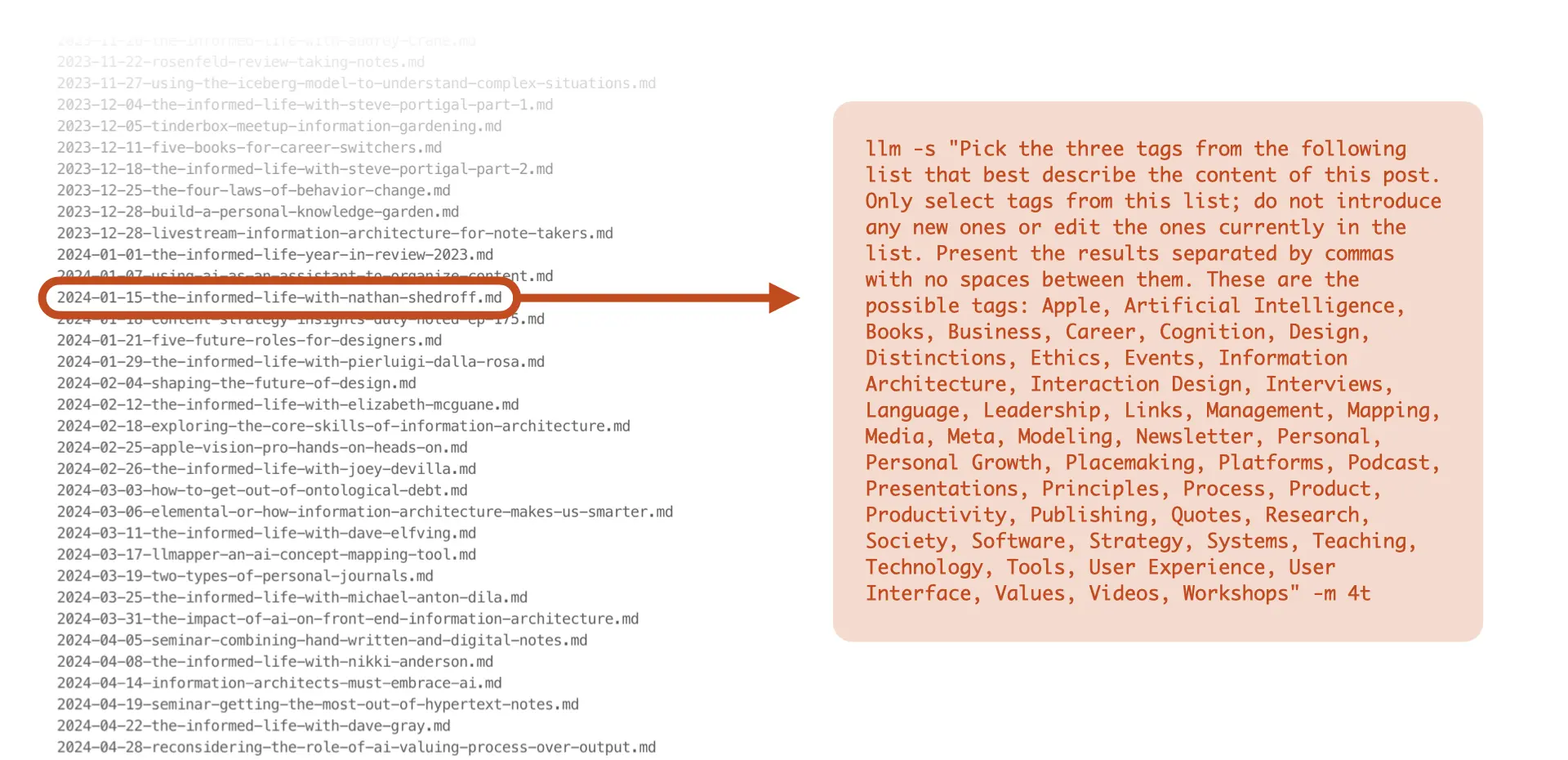

My site uses Jekyll, which is a static site generator. All the content is actually stored as Markdown files on my computer. The site gets re-rendered as a static HTML files every time I update it. To change all the tags, I would have to revisit all of those posts manually and add tags to each. This is an ideal use for generative AI.

So I built a set of scripts that use the OpenAI API to ‘read’ every Markdown file in my blog and ask GPT-4 to assign three tags from a preset taxonomy to each post on the site. I’m not going to go into details on how I did this here, I have written about it on my blog. The point is, this is tedious work and I would rather have an LLM do it.

And GPT-4 did a fine job — in about a third of the time it would have taken me. Actually, it was only about a fifth of my time because much of the work happened without my even being there: I went grocery shopping while GPT re-tagged my site. The outcome was about as good as I would have gotten if I had done it myself.

But I would have never done it myself, because this would have taken me too much time and I couldn’t have justified paying someone else to do it. Tools to do this kind of thing have been available since the 1990s but they have been relatively specialized and expensive. Now pretty much anybody with a little bit of knowledge can tap LLMs to do this work for them. Again, kind of like what spreadsheets did: it democratizes the technology.

My taxonomy also evolved as a result of this work. GPT proposed tags I hadn’t considered in my originally. So it didn’t just do the menial task of re-tagging everything; it also helped me make my content more discoverable. It didn’t just help with a menial task; in some ways it was a collaborator in designing the information architecture for this site.

I think that experiments like this one have important implications for our work. The fact that these technologies exist changes our field even if we choose to stay at the level of augmentation. In other words, even if these things don’t lead to artificial general intelligence — and I think that we are pretty far from that — they change how the discipline works.

Here are three implications I see for our work.

Implication 1: AI and Data Are New Design Materials

The first is that with generative AI in the world, data and metadata become a new kind of design material. This is something that Jodi Forlizzi and her colleagues have spoken and written about: the idea that we should think of AI not just as a set of technologies but as a new kind of design material that enables new capabilities.

Thinking back to architecture, if you think of concrete as a building material, the ancient Romans had concrete but they didn’t have elevators. With elevators, you can think about the potential for concrete in a different way. We’ve had data for a long time. Now we can process data at different rates and at different scales. It leads us to think about data and metadata as a new kind of design material.

When you look at a system that you’re designing now, if you understand its data structures, you can think about different ways to use AI to deliver new kinds of experiences. Because with generative AI, you now have ways of working with that data at greater scale, faster and more efficiently. I expect that this is going to lead to a shift in how digital experiences are designed. But that’s not the only reason why there will be a shift.

Implication 2: Many Jobs are Going Away

This leads me to the second implication. It’s something that I’ve been telling my students now for a couple of years: screen-level interactions will become commoditized as a result of these tools. I am convinced that there will be fewer people designing screen-level experiences.

I have this kind of dark joke that I’ve been saying for the last couple of years, that design operations is a placeholder phrase we use until we can plug generative AI into design systems. Because once you have telemetry — what is happening in real-time with a digital product — plus a design system that articulates the product’s interaction vocabulary, and AI capable of reconfiguring end-user experiences in real-time, then there will be much reduced need for people designing screen-level things.

As a result, there will be fewer jobs in this space. I don’t think design is going away, but designers will focus a higher levels of abstraction. So if you are focused on user interface design, consider thinking about shifting your focus to higher levels of abstraction, including information architecture.

Implication 3: IAs are Well-suited to Working With AI

This might sound self-serving, but I do believe that it is true, because — and this brings me to the third and final implication — as Rachel Price pointed out in this year’s Information Architecture Conference, information architects are especially well-suited to designing AI-powered systems.

This is for several reasons. For one thing, LLMs are a natural counterpart to our work because we are the language people in UX. Semantic distinctions and data structures are key to our work. We also grok the technology, its capabilities and constraints, much like architects need to understand what they can do with concrete and steel and elevators.

But we’re not driven by the technology per se, but by how the technology can serve user needs. This is still a human-centered discipline, a discipline that looks to make information more understandable and usable by people — and to do it ethically. Like Rachel said, we are well positioned to be the people who help guide the use of these technologies towards more humane ends.

Creating New Value by Design

Make no mistake, this change is upon us and the world is going to look very different soon — not just for us as designers, but as users of these systems. Manipulating symbols at scale — the basic capability that language models and generative AI models offer — opens new dimensions for us as designers, much as elevators literally open the new dimension for architects.

When you open a new dimension, you create new spaces for possibility, especially the possibility of creating new value. Think of how much literal real estate value vertical buildings created in New York. But I’m convinced that unlocking this value — not just financial, but human too — will only happen by design. And information architects are well-suited to ensure that these new technologies create value for people.

So this is my final message to you and the main thing I wanted to share with you today: It is very important that you learn about artificial intelligence. And not just in theory. You can read a lot about this stuff and there’s a lot of stuff to read right now because this is such a hot subject. But it’s very important that you roll up your sleeves and work with this technology directly.

Run experiments. Get familiar with the APIs. When you do that, you will cut through the hype. The hype threatens to obscure LLMs’ possibilities. But when you get involved, when you play around with them, you will get a new appreciation for what this material is and what it can do.

There’s a lot riding on this. These technologies will have a big impact on our world, much like elevators led to vertical cities. If you are at this conference to learn about information architecture, you’re especially well suited to do something good with it. I wish you luck as you enter this new space. Thank you.